– Kazuhiko Fukuji (Thank you, Tetsugan)

Is Zen weak on compassion teachings?

Zen teacher Norman Fischer Rōshi has written that he considers it “… a serious weakness in Zen: its deficiency in explicit teachings on compassion.” (1)

In this post, I’ll present another perspective, however, I’d like to note that although I disagree with Fischer Rōshi on this point, his book, Training in Compassion: Zen Teachings on the Practice of Lojong, has helped many people to remember and actualize the buddhadharma in daily life. In addition, a member of the Nebraska Zen Center offers Mindful Self-Compassion courses at the center. So I’m not a compassion-practice hater.

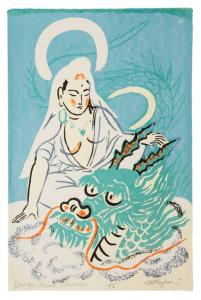

The first point I’d like to make is that we do find explicit teaching on compassion in many Zen sources, for example, the Ten-Line Kannon Sutra and The Universal Gateway – both essential aspects of the Zen liturgy that provide instructions for the spirit and detail of compassion practice.

In addition, Dōgen uses the word “compassion” eighty-six times in Tanahashi and Levitt’s translation of the Shobogenzo, where he has a fascicle on compassion practice, “Avalokiteshvara” (or “Kannon”), based on a wonderful kōan that includes this exchange:

Yúnyán asked, “The bodhisattva of great compassion uses the many hands and eyes for what?”

Dàowú said, “As if it’s night and a person gropes with their hand behind their body for the pillow.” (2)

In addition, many of the kōans in the Harada-Yasutani curriculum could be considered compassion kōans, for example, Songyuan Chongyue’s “Why can’t clear-eyed people cut the blood-red thread?”

Finally, when zazen and daily life are about regarding the cries of the world and reaching back for a pillow to comfort all living beings (i.e., meeting all beings with compassion), all of Zen is about compassion.

Now, you might say, “Is that it? Is that all you got?”

And then I might say, “Isn’t that enough? Compassion is more about practice, after all, then a huge set of teachings, or a particular personal psychological state.”

Okay, well, on the other hand, if you really want more, there is something more, one of the central rubrics for training in both the Sōtō and Rinzai lineages, Dòngshān‘s Five Ranks, and particularly the third rank. Digging into the teaching for this rank, though, I see some of the commentaries have a tilt that support Fischer Rōshi’s perspective. Before I explain that, though, some back story is necessary.

Dòngshān‘s Five Ranks

Dòngshān Liángjiè (807–869) is attributed with systematizing the Five Ranks of the true and biased (3). The underlying principle is that the truth will set us free, and that the relationship between the true and the biased shifts, sometimes dramatically, over the course of practice. The Five Ranks are first, “biased within true” (正中偏), second, “true within biased” (偏中正), third “returning within true” (正中來), fourth, “reaching within unity” (兼中至), and fifth, arrival within unity (兼中到).

Ross Bolleter Rōshi, an Australian Zen teacher in the Harada-Yasutani lineage, offers this lovely summary (note: he prefers “mode” to “rank”):

“Through the five modes of [true] and [biased] we have discovered that, although we awaken in very individual ways, we can broadly discern staging posts on the path…. We can say that, initially, we experience emptiness, and begin a lifetime’s work of embodying it. We awaken to our intimate connection to all that is, realize the subtlety of words, and then letting go of any preoccupation with hidden understandings, we awaken ourselves, and others, in the thick of the world and its suffering. Finally, we emerge transformed, but find it difficult to say where we have been, or how we have traveled. We live our life—with its give and take, joy and sorrow, increase and decline—as the Way.” (4)

Within our Zen Way, as expressed by Bolleter, compassion is the heart of the great matter of birth and death. So is awakening. “We experience emptiness,” says Bolleter, glossing the first rank of “biased within true,” “and begin a lifetime’s work of embodying it.” Then Bolleter says, “We awaken to our intimate connection to all that is,” glossing the second rank, “true within biased.” Bolleter, continues with the third rank, “returning within true:” “Then letting go of any preoccupation with hidden understandings, we awaken ourselves, and others, in the thick of the world and its suffering.”

Returning within true

The third rank, “returning within true,” is most relevant for our exploration of compassion and Zen, so let’s dig into the dirty detail by examining Dòngshān’s verse for this rank:

“Within mu there is a road out of dust and dirt

無中有路 隔塵埃

Now only do not touch the taboo word

但能不觸 當今諱

also surpass the previous dynasty’s capacity to cut off tongues.” (5)

也勝前朝 斷舌才

At first glance, this verse might not seem to be about compassion at all, but about really, really shutting up. “Dust and dirt” usually represent “the world of differentiation” in Zen-speak. Thus, the first line seems to say that within mu (i.e., “no” or “non”) there is a process of being free of the mess of worldly concerns. Where’s the compassion?

In the second line, “the taboo word” is often interpreted as representing the emperor’s name, the prime taboo word in ancient China, which in turn is understood in the Zen context as talking about awakening. In this light, the point seems to be that from deep silence, exactly one with the true, we will silence the whole world. Seen in this light, the verse has a “silent illuminationy” feeling – passive and not exuding compassion, to say the least, but more about “How cool it is that I can so completely shut up that I can shut you up too.”

This seems to be the most common interpretation, although without the attitude, of Dòngshān’s verse for the third rank. If such an important system underlying Zen training is more about shutting up than liberating beings, it would appear that Fischer Rōshi is correct – Zen is deficient in compassion.

Out of Dust and Dirt or Out to Dust and Dirt?

However, there are other ways to read “out of dust and dirt,” and these readings flip the meaning of the verse. In The Discourse on the Inexhaustible Lamp of the Zen School, Daibi Rōshi, an early Twentieth Century Rinzai Zen master, said, “… Out of ‘dust and dirt’ are taken to mean the ‘dust and dirt’ of Satori.” (6)

Multiple levels of meaning, including contradictory ones, are common in Zen, especially in Dōgen’s teaching and in kōan introspection. Even standard metaphors like “dust and dirt” are revivified, like new wine in old bottles. “Out of dust and dirt” can also mean to shake off the stink of attainment and get to work liberating beings.

Further, Daibi Rōshi adds this twist:

“‘Within Mu is the Way that leads out of dust and dirt’ may also be read as ‘Within Mu is the Way that leads out to dust and dirt….’ When read as ‘out to,’ ‘dust and dirt’ refer to the realm of sentient beings, and mean the dust and dirt of wisdom and differentiation. According to this, as the [true] and the [biased] are not two, and there are neither sentient beings to be assisted nor are there any afflicting passions, so the way of the great compassion that is impartial leads out to the wisdom of the differentiation of dust and dirt. This constitutes the affinity link with the Buddha-Realm.”

When “dust and dirt” refer to being free from any ideas of attainment, any stink of Satori, we are then free to fully go out to embrace the dust and dirt of the world. “Not touching a taboo word” (the second line of the verse), in this light, means that we don’t find such a word in all the dictionaries of all the world’s languages, and we are free to devote ourselves to the awakening of all living beings.

This seems to be a hidden understanding and it is found through “…letting go of any preoccupation with hidden understandings,” as Bolleter put it and continued:

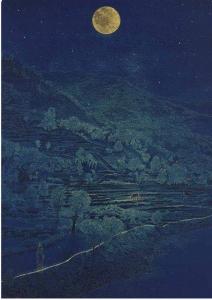

“Words that avowedly name the emperor—that discuss enlightenment itself—can themselves be a subtle and low lit means to avoid breaking the taboo on naming the emperor, who by the way is as apparent as this warm autumn day, the doves cooing in the frangipani, or the low hush of distant traffic.” (7)

And we “surpass the previous dynasty’s capacity to cut off tongues” by hearing from each tongue the rolling truth of the buddha dharma, and sharing it with friends far and near.

Indeed, in my view, rearticulating the role of compassion in Zen was Hakuin and his successors greatest contribution to contemporary Zen. For more, see “What’s Love Got To Do With It? The Most Important Thing About Hakuin’s Teaching.”

For example, Hakuin said, “In this [third] rank, the Mahayana Bodhisattvas do not dwell within the realization attained. Great compassion shines forth unconditionally as they are carried forward on the four great and pure vows into the ocean of free and unrestricted activity….” (8)

So let’s get to it.

(1) Norman Fischer, Training in Compassion: Zen Teachings on the Practice of Lojong, Kindle location 148.

(2) Dogen, Treasury of the True Dharma Eye: Zen Master Dogen’s Shobo Genzo, translators Tanahashi and Levitt, Kindle location 8979. The translation of the kōan excerpt is by the author.

(3) For much more on the Five Ranks, see Complete Poison Blossoms from a Thicket of Thorn, trs., Norman Waddell, pp. 197-221; Ross Bolleter’s The Five Ranks: Keys to Enlightenment; and Taigen Dan Leighton’s Just This Is It: Dongshan and the Teaching of Suchness.

(4) Bolleter, Kindle location 1377.

(5) Translation by the author.

(6) Torei Enji and Daibi Roshi, The Discourse on the Inexhaustible Lamp of the Zen School, translated, Yoko Okuda, p. 269.

(7) Bolleter, Kindle location 1757.

(8) Waddell, p. 206.

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Sensei, with the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training, an internet-based Zen community. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, is now available (Shambhala). He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin Katagiri. Click here to support the teaching practice of Dōshō Rōshi at Patreon.