Was Hakuin Ekaku (1686 – 1768), the great Japanese revitalizer of Rinzai Zen and the inspiration for much of modern-day kōan introspection, a hater of that other Zen school – Sōtō Zen? What would have happened if Hakuin and a Sōtō monk had met face-to-face?

The short answer to the first question is “No, Hakuin was not a Sōtō hater.”

The short answer to the second question is that it happened a lot and, well, see below. From Hakuin’s reports, a good number of Sōtō monks studied with him and when Hakuin was a young monk, he also studied in Sōtō monasteries.

Hakuin did, however, have blistering criticisms of the silent illumination tendencies of the Sōtō Zen of his day. See my Hakuin’s Blistering Criticisms of Sōtō Zen: Who and What for a more detailed look at this. Briefly, Hakuin had at least these four criticisms:

- The zazen of silent illumination Zen is a passive pursuit of a state of perfect purity, and sometimes just a do-nothing practice of zoning out, sleeping, and generally wasting the resources of donors.

- Silent illumination Zen takes kensho as something that is inherent, too pure to experience, or already realized, and so denies the reality and significance of a personal experience of kenshō.

- Because silent illumination Zen denies kenshō, it has no inclination for post-satori development like Hakuin’s method for post-satori practice – digging into many kōans and sutras.

- Silent illumination Zen takes the dharma as a belief system and so the power of such teachings as “formlessness” and “no mind” is lost in doctrinal dharma (as opposed to personally putting it to work).

You may notice that some of the above seem to apply to much of today’s Sōtō Zen. Nevertheless….

Rinzai and Sōtō: Never the Twain Shall Meet?

Despite his often-repeated negative criticisms of Sōtō Zen, especially Sōtō with a silent illumination emphasis, Hakuin borrowed the Five Ranks teaching of Dòngshān from the Cáodòng (Sōtō) school, rather than use Línjì‘s Four Views, for example. Hakuin received instruction in the Five Ranks from either his main teacher, Shōju Rōjin (aka, Dōkyū Etan, 1642–1721), or from his own encounter with Sōtō priests at Inryō-ji, teh Sōtō temple referred to above that Hakuin stayed at for a practice period shortly after he left Shōju Rōshi. (1) Or perhaps both.

By this time, Hakuin was already suffering from Zen sickness, but had yet to meet Hakuyū and learn the “soft-butter method” that cured him. (2) Due to Hakuin’s affinity with the Five Ranks, they now serve as central (but quiet) organizing principles in both the contemporary Rinzai kōan curriculum and the reformed Hakuin-Yasutani kōan curriculum transplanted to the West by the likes of Rōshis Yasutani, Maezumi, Kapleau, and Aitken.

In Hakuin’s day, it should be noted, Sōtō and Rinzai were not as separate as they are today, at least, in Japan, where I’m told that if a Sōtō monk wants to train in a Rinzai monastery, they would need to reordain. Apparently, the reverse is also the case. This was not the case in Hakuin’s time.

In my view, it is a sad development. I have greatly benefited from study in Rinzai Zen and in the Harada-Yasutani kōan tradition, and would like to see more Sōtō practitioners have that opportunity, and visa versa. At the same time, both Sōtō and Rinzai lineages have a “family style” with integrity and could both make important contributions to sincere practitioners more interested in awakening than to sectarian purity, as well as to our fledgling global culture. So my hope is that both continue vigorously.

To complicate the situation, however, there are also some lineages that are neither Sōtō nor Rinzai in the traditional sense. I’m referring to all those who are descendents of Harada Daiūn Rōshi (1871 – 1961), the Sōtō monk who trained extensively in Rinzai Zen and received inka shōmei (proof of succession) from Tōyōta Dōkutan Rōshi (1840-1917), a Rinzai Zen master. Harada Daiūn Rōshi had a long teaching career in a Sōtō monastery, Hōshinji, used a reformed kōan curriculum, and also trained lay people together with monks, something that just was not done in his day.

Some of Harada Daiūn Rōshi’s present day successors regard themselves as Rinzai, some see themselves as Sōtō. In my case, due to the good steeping in Sōtō I received from my time with Katagiri Roshi, I emphasize the flow of Sōtō (aka, “forms”), and the importance of Dōgen’s teaching. At the same time, I think that kōan introspection inspired by Hakuin and Tōrei, is the greatest meditation innovation since the Buddha saw the morning star. From this hybrid perspective, Dōgen’s teaching is esteemed but not privileged. After all, there have been a lot of great Zen teachers.

But let’s get back to Inryō-ji

where Hakuin had a lovely practice period in a Sōtō monastery. Later, he described fifty monks practicing earnestly, including a monk named Jukaku Jōza, someone Hakuin felt he’d know for many years, and who Hakuin recognized for his genuine aspiration for the Way. At first, though, Hakuin saw him as “…an old man who seemed half-demented, with an unsightly face and a robe hanging in tatters from his body . . . who ran off when he saw me coming.” (2)

Fortunately, Hakuin sat next to Jukaku during the 90-day practice session. When Hakuin finally cornered Jukaku and they had a chance to talk, Hakuin says that they found their minds to be in complete agreement. This inspired them to sit an extreme sesshin together.

Here’s how Hakuin told the story:

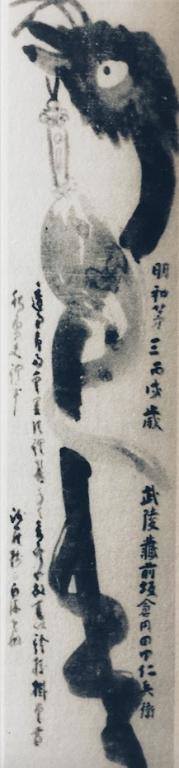

“On one occasion, the two of us engaged in a private practice session. We pledged to continue it for seven days and nights. No sleep. No lying down. We cut a three-foot section of bamboo and fashioned it into a makeshift shippei. We sat facing each other with the shippei placed on the ground between us. We agreed that if one of us saw the other’s eyelids drop, even for a split second, he would grab the staff and crack him with it between the eyes. For seven days, we sat ramrod-straight, teeth clenched tightly in total silence. Not so much as an eyelash quivered. Right through to the end of the seventh night, neither one of us had occasion to reach for that cudgel. One night, a heavy snowfall blanketed the area. The dull, muffled thud of snow falling from the branches of the trees created a sense of extraordinary stillness and purity. I made an attempt at a poem to describe the joy I felt:

If only you could hear

the sound of snow

falling late at night

from the trees

of the old temple

in Shinoda!” (4)

The abbot of the Inryō-ji, a Sōtō lineage monk, even asked Hakuin, a Rinzai lineage monk, to be his successor at Inryō-ji. Hakuin seems to have been tempted, noting that “…the temple holdings included some very rich and productive fields, making it possible to provide for forty or even fifty visiting monks at annual summer retreats.” (5)

It wasn’t an easy choice, but Hakuin eventually decided he was not ready to settle down, so he declined the offer, and went on with his pilgrimage. On the day that Hakuin left Inryō-ji, he reported that “… Jukaku slipped away from the assembly, walked along at my side for several leagues, and then turned back.” (6)

So tender!

What would happen if Hakuin met a Sōtō monk face-to-face? In this case, they entangled eyebrows, and became fast dharma friends.

(1) See Complete Poison Blossoms from a Thicket of Thorn, trs., Norman Waddell, “58. Informal Talk on a Winter Night,” for Hakuin on Rujing and Dōgen. Here and in other places, Hakuin spoke highly of Dōgen, who, by the way, was also critical of silent illumination.

(2) See Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin, trs., Norman Waddell, “The Soft Butter Method,” pp. 105-107.

(3) Precious Mirror Cave, trs., Norman Waddell, pp. 185–6.

(4) Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin, trs., Norman Waddell, pp. 50-51.

(5) Ibid.

(6) Ibid.

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Sensei, with the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training, an internet-based Zen community. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, is now available (Shambhala). He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin Katagiri. Click here to support the teaching practice of Dōshō Rōshi at Patreon.