Let’s get right down to it

Break through is a must if you want to verify the truth of this one great life and not just take others’ words for it, hiding behind the Buddha’s robes, as it were. Or hiding inside your own robes. Hiding in the bells and smells of Zen orthodoxy. Or spending a dharma career trying to talk others into believing that non-enlightenment is really enlightenment. Exhausting!

Rather than just do a little bit of good for a short period of time, the aspiring bodhisattva vows to profoundly benefit living beings by helping them awaken. As I said above, for this, break through is a must. You can’t help beings break through unless you’ve done it your-nonself. Then, in addition to the exquisite joy that comes from doing what can be done with this life, blabbing on about it might just flow from your heart.

A more typical message – in contrast to saying break through is a must – was exemplified in a dharma talk I recently heard from a teacher in one of the large Sōtō centers in America. The speaker said that because aspiring to awaken is a desire like any other desire, and that awakening doesn’t come when we want it, and when some people awaken and others do not, it creates an unsettling power dynamic in the community, they do not emphasize break through at all in their community, and instead emphasize how we’re all already Buddhas.

First, if you cannot tell the difference between the desire for fame and gain and aspiring to awaken for the benefit of all living beings, I’d suggest attending to these feelings with more subtle mindfulness, and see what you find.

Just because you can quote Sawaki Rōshi doesn’t make it true.

And, yes, there are issues that arise when we focus on kenshō, but if Buddhism stops being about awakening, what’s the point? We have psychotherapy, secular mindfulness, pharmacology, Netflix, and many other things to help people feel better, so if Zen practice is not about awakening, and instead is about becoming a “ceremonial technician,” for example, the end of Zen is near at hand. And appropriately so.

Don’t throw awakening out with the bathwater!

In contrast, here is the attitude that Dàhuì recommends:

“I vow that this mind of mine will be firm and will never retrogress. Relying on the protection of the buddhas, I will meet a good teacher, at a single word from them forget life-death, realize unexcelled perfect awakening, and perpetuate the wisdom-life of the buddhas, in order to repay my debt of enormous gratitude to the buddhas.” (1)

So refreshing!

Dàhuì himself made this additional vow:

“I would rather substitute this body of mine for that of all sentient beings and undergo sufferings in the hells than ever with my words compromise the buddhadharma [by bending to accommodate] customary etiquette and in the process blinding everyone [i.e., what I am about to say to you is not a case of bending to accommodate your feelings].” (2)

Well, I’ve totally jumped the gun of this post, placing the cart in front of the horse. To paraphrase the translators’ bracketed clarification, what I’ve said to you is not a case of bending to accommodate your feelings. But I grew up with in-depth training in Northern Minnesota nice, which means I’ve just got to add, “Sorry about that.”

Before this kenshō rant, I should have said that this is the ninth of ten posts in this series, so now, after the horse left the barn nearly six-hundred words ago, I’ll share the usual series introduction and disclaimer:

In the recent translation of The Letters of Chan Master Dàhuì Pǔjué, translators Jeffrey L. Broughton and Elise Yoko Watanabe offer nine themes, motifs, that emerge in the letters about how to do keyword practice (話頭 huàtóu, Japanese, watō). I’ve been sharing them on the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training for students working with keywords (e.g., mu), and I’ll also be sharing them here for others who might be interested. Close study of an ancient text can help both students and teachers notice details of the method and refresh their practice spirit. If you are working with a keyword with another teacher, consult with them, of course, and rely on their guidance.

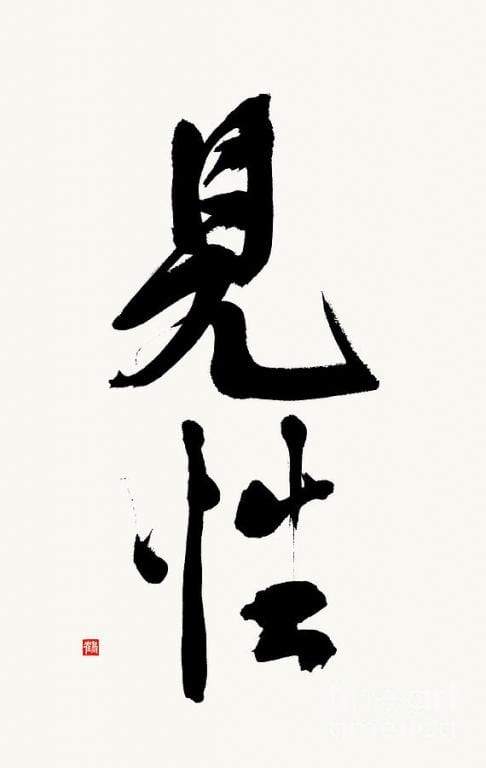

Theme 8: You must “break through” or “pass through” the keyword

This breaking through or passing through leads to a state wherein you don’t have to ask anything of anybody—you know for yourself:

Letter #29.3: “Also, if your mind is agitated, just lift to awareness the keyword of ‘dog has no buddha-nature’ [i.e., wu/mu/no 無]. The words of the buddhas, the words of the ancestors, the words of the old monks of all the regions have myriad differences; but, if you can break through this word mu 無, you’ll break through all of them at the very same time, without having to ask anyone anything. If you intently ask questions of other people about the words of the buddhas, about the words of the ancestors, and about the words of the old monks of all the regions, then in endless aeons you’ll never attain awakening! (3)

Comments

Breaking through all the words and teachings of the buddhas and ancestors in one stroke? Possible. And the only one way to find out if you’ve done it is to find a teacher that’s done rigorous training and check your understanding. Probably, you’ve (at best) knocked a hole in the wall. However, if you are really clear, like clear-as-Shakyamuni clear, why not inquire of others, and play together with the dharma mud ball?

Some of the practitioners I’ve met who have come to me reporting a previous kenshō, actually have. And a fair number, the majority, have mistaken samadhi or boon experiences for kenshō. Others seem to have had a glimpse of true nature, but it’s become a calcified part of their identity, and so putting it to use in ongoing practice verification to benefit others, takes some time and skillful practice.

But despite what Dàhuì seems to be saying from this extract about not needing to ask anyone anything, the full text and annotations makes it clear that he is addressing another issue – instead of doing the practice of lifting the keyword, Secretariat Drafter Lü, to whom letter #29 is addressed, was inquiring about traveling around asking questions of various teachers, depleting his energy for the Way. In that context, Dàhuì encourages him to do diligent keyword practice and see for himself.

Just like old Dōgen said, “Why abandon your own sitting place, disrespectfully wandering through another country’s dust? If you make one mistaken step, you miss the crossing over that is in your face.” (4)

Traveling around with straw sandals, or via Zoom, in order to collect an impressive bevy of stories, “Teachers I’ve Asked About the Dharma,” is a waste of precious time. Focus! Only doing diligent practice will open up awakening, not the number of hours you log on Facebook or Twitter either! And with awakening, personally knowing the truth of the buddhadharma, rather than relying on the words of others, no matter how venerable they might be, such that you can truly be of service to the many beings wandering in life-death.

In other words, asking a well-trained and clear-eyed teacher about the dharma ain’t going to magically awaken you.

Usually.

Unless and until you do the work and suddenly are ready, like the persimmon that goes SPLAT! Working with a teacher, breaking through, verifying your kenshō in face-to-face meetings, and benefiting others is the Way.

Secretariat Drafter Lü might be the type of guy (yes, they’re almost always guys), who after a dharma talk begin a “question” with, “Well, Katagiri/Suzuki/Uchiyama/Maezumi (etc.) Rōshi once said, “Blah, blah, blah.”

Where does this end?

(1) The Letters of Chan Master Dàhuì Pǔjué, “1.4: Shows the mental work necessary to extinguish habit-energy from past lives,” trans. Jeffrey L. Broughton and Elise Yoko Watanabe. Modified.

(2) Op. cit., “7.1: Dahui certifies Li’s awakening.”

(3) Op. cit., “Introduction: Recurring Motifs in Huatou Practice.”

(4) Eihei Dōgen, “Fukanzazengi,” (“General Advice for the Zazen Ceremony”), trans. Dosho Port.

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Sensei, with the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training, an internet-based Zen community. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, is now available (Shambhala). He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin Katagiri. Click here to support the teaching practice of Dōshō Rōshi.