Practice at Bukkokuji was like living at grandpa’s house. Harada Tangen Rōshi set the rules and everyone followed them – or left. If you didn’t think that Grandpa Rōshi-sama was setting rules that were all about your awakening, then you were in the wrong place, and also would be told to take the next train to Kyōto. This clarity made life incredibly simple.

Lately, as Tetsugan Ōshō and I talk with each other about our teaching practice, the Vine of Obstacles, the following vignette keeps coming to mind. But to appreciate this story, you first need to know that winter at Bukkokuji could be long and cold, extending from Rohatsu in December until April with temperatures that hardly varied +/- 3 degrees on either side of freezing. As monastics we were allowed winter robes, and I was blessed to have a wool kimono and koromo sewn for me by my dharma mother, Tomoe Katagiri (and arriving just in time). In addition to winter robes, most monks wore a thin inner-layer of long underwear, but otherwise we just had our “one-doing power” to keep us warm – there was no central heating system or any room heaters. And, no hats or socks were allowed, except in the sleeping quarters.

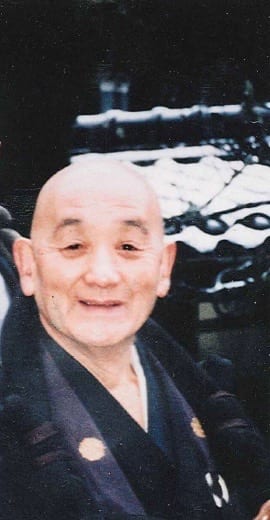

I also want to add that Harada Tangen Rōshi was the most generous and joyful person that I’ve ever met.

One day in the midst of the penetrating cold of winter, a young male American arrived, carrying a large backpack. Apparently, he had exchanged letters with the Rōshi, but us monks only knew he was coming – and that he was an American – because we could hear him laughing loudly (as only Americans do when guests in a foreign land) for at least a couple blocks before he reached the main gate. We Americans are exceptional, after all, in at least this one way.

Tangen Rōshi met the young fellow for tea in the Buddha Hall. Surprisingly, the Rōshi had his attendant bring in a small electric heater. However, because the attendant set up the heater in an odd way so that it wasn’t blowing on either the host or the guest, Tangen Rōshi invited the guest to sit closer to the heater and in the airflow of the delicious warmth. Any of us monks would have thrown our bodies on the floor and basked in the temporary reprieve from the bitter winter. The young American, though, declined the Rōshi’s kindness. The Rōshi then bowed and invited the fellow to leave. Surprisingly, despite his traveling from afar for the opportunity to study Zen, after about a minute, his training at Bukkōkuji came to an abrupt end.

Many of us monks had seen the American arrive and depart in short order. A few of us, including me, had found a reason to peak into the Buddha Hall to get a look at the new arrival. None of us knew the reason for his short tenure until a few days later when the Rōshi explained about the heater, his offer, and the guest’s refusal.

“If he would not listen to me,” explained Rōshi-sama, “and accept the warmth of a heater on a cold winter day, it seemed unlikely that he would listen to my instructions for letting go and dropping body-mind. I am an old man now and there isn’t time for me to train such a person.”