First, a Brief Update

As I hope you have heard, The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, translated with commentary by me, is due out on February 2. To preorder with a 30% discount and see reviews by Steven Heine, John Tarrant, Meido Moore, Bodhin Kjolhede, and Henry Shukman click here.

You can also browse inside and read Melissa Blacker Roshi’s forward, my introduction, and the first case.

I’ll soon be sharing some excerpts from the book here.

Finally, in terms of FYIs, this is a good time to join the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training. Click here for an overview and click here for more detailed information. It’s a good idea, btw, to attend several of our Saturday Open Zen (via Zoom) sessions, 10:00am-11:15amCT, to see if you resonate with the teachers and the community. Sign up for the email updates with information about these here.

Meanwhile, I’ve been working on another project, and will share a section of that below about disclosing Zen insight, Bodhidharma’s separate transmission, and warming ourselves before the fire. The passage is from the Tongxuan Baiwen (通玄百問), Going Through the Mystery’s One Hundred Questions. The text features three Caodong (Japanese, Soto) teachers from 13th century China: Tongxuan (Going Through the Mystery) asks the questions; Wansong (the commentator in The Book of Serenity) gives brief four or five character response; and Linquan (the commentator in The Empty Valley Collection) adds a verse. Here it is, followed by my comments:

Question 80: Disclosing Zen Insight

Tongxuan asked, “The founding teacher’s separate transmission outside the teaching – to test, I invite the Zen person to disclose their insight.”

Wansong replied, “A great flower blossom net.”

Linquan’s Verse

A great flower blossom net

Not willing to completely approve

Standing in the snow, holding up a flower

In the past they had barely met

Still he didn’t spare his eyebrows and announced the noble wisdom

Warm weather turns cold, trembling, warm yourself facing the fire

Commentary

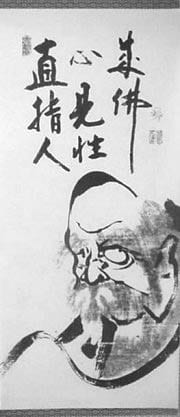

Tongxuan begins his question with a reference to a famous verse by our founding teacher, Bodhidharma:

Separate transmission outside teaching

Not established words texts

Point directly human heart

See nature realize buddha

Another translation has it like this:

A special transmission outside the scriptures

Not founded upon words and letters;

By pointing directly to [one’s] mind

It lets one see into [one’s own true] nature and [thus] attain Buddhahood.

The first documented occurrence of this verse was by Shexian Guisheng (n.d.), a late tenth-, early eleventh-century master in the Linji line, and attributed to Bodhidharma. Our Zen Way is not established in words or texts, even those words or texts that say our Way is not established on words or texts. Indeed, the source for the stories we tell are finally unknowable and essentially unreliable. What is reliable?

First, a word or two about the translation of Bodhidharma’s verse. Each of the four lines of the verse has just four characters, so it has a symmetrical visual presentation:

教外別傳

不立文字

直指人心

見性成佛

You’ll see above that I’ve rendered it this way as well – four lines with four words each, so sixteen words in total – although, in English the symmetry doesn’t quite work as well.

The translator in the second version has added a lot of words to this text, for a total of thirty-one. Whenever a translation is almost twice as long as the original, the translator is very likely adding meaning, doing the reader’s work for them, by saying what the translator thinks the original says rather than letting the original speak.

With translation, though, there is always interpretation and it is impossible to succeed.

Specifically, in this case, the second translation makes the verse prescriptive – by pointing at the mind we see our true nature and thus attain buddhahood. It makes sense, but those elements are added.

The verse can also be interpreted in other ways, including as descriptive: “Direct pointing human heart.” From this perspective, the human heart is already directly pointing. Always. Likewise, “See nature realize buddha” can also be seen as descriptive. When we see the essential truth, aka, true nature (見性, kensho), we real-ize buddha. We do the awake buddha thing. And when we do the buddha thing, we are awake.

In this context, Tongxuan boldly asks Wansong to show him the nature that he has seen and is now seeing.

“A great flower blossom net,” reports Wansong. Such a beautiful image to embody in zazen. And off the cushion.

For the characters that Wansong uses for “great,” 摩訶, transliterate the Sanskrit, “Maha,” like in Mahayana, the Great Vehicle, instead of the more common Chinese “great,” 大. In this spirit, “This mind itself is buddha” is a Maha flower blossom net, like the net of Indra that extends throughout the multiverse, with a multifaceted jewel at each vertex.

And look! In this net of jewels is a luminous self, a word, an idea, a whole text – quite a bouquet of flower blossoms!

What about Linquan’s verse? Well, to appreciate that more fully, you may need some more context.

As you may know, as the story goes, at an advanced age, the great Indian sage, Bodhidharma, came to China and managed to get an interview with the emperor. However, the interview went badly, especially when he failed to know who he was, so he went north, and then sat facing a wall at Shaolin for nine years. Huike, a desperado waiting for a train, applied to study with the great sage by standing the snow. He finally cut off his arm to demonstrate his sincerity. In other words, “Standing in the snow, holding up a flower.”

The Buddha held up a flower on Vulture Peak and Mahakasyapa smiled. But here we have Huike’s bloody arm held up. When we wholeheartedly enter the way, we often find that we have to give up something of great value. It might seem like an arm or a fixed idea of who we are, but it turns out to be a flower blossom.

In the Soto tradition in Japan, in the evening of December 9, following the seven-day Rohatsu sesshin, Huike’s picture is put on the altar, as this is the day that it is believed that Huike cut off his arm. Then the monks again sit all through the night. In the morning of December 10, sutras are recited to requite Huike’s compassionate blessings. That which Huike had given up, is honored still.

And although Bodhidharma (and by extension, Wansong) and all the ancestors, held nothing back in expressing the noble wisdom, even eyebrows or arms, Bodhidharma and Huike had barely gotten acquainted, so the old barbarian did not approve.

Standing all night in waist deep snow and cutting off an arm, after all, is not necessarily seeing nature, doing buddha. So

don’t wait for the person standing in the snow

to cut off their arm help them now

-Ikkyu

Friend, the weather is turning cold, and, oh dear, you are trembling. Best turn toward the fire and get some warmth.

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Ōshō, with the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training, an internet-based Zen community. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans is due out in February, 2021 (Shambhala). He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin.

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Ōshō, with the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training, an internet-based Zen community. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans is due out in February, 2021 (Shambhala). He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin.