Introduction

When I was translating The Record of Empty Hall and working on the commentary, a respectable scholar sent me a copy of Xutang’s preface for Dogen’s Eihei Goroku, that is, the abridged record of Dogen. The text was mostly the mix of Chinese characters and Japanese syllabaries and quite over my head. Fortunately, I persisted.

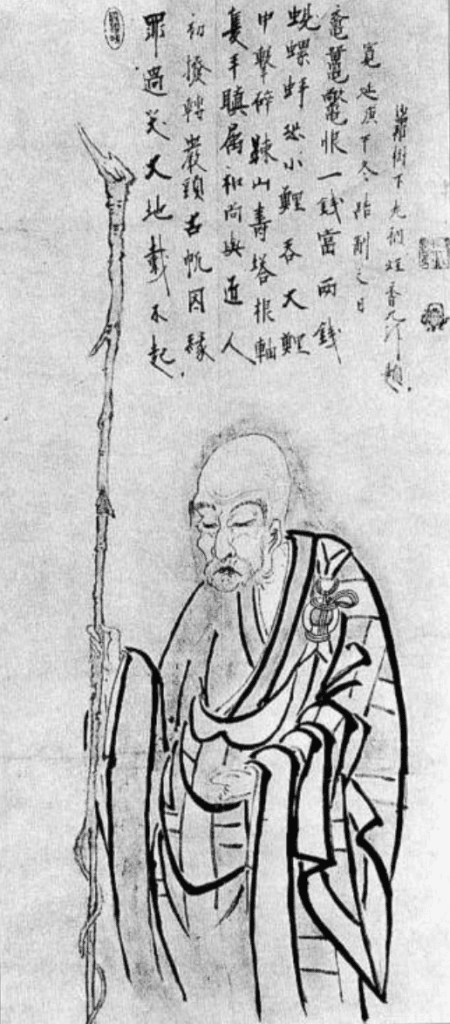

For many reasons, Xutang (1185-1269; English, Empty Hall) is an enormously important teacher in the 13th Century Linji lineage Chan, not the least of which is that he had several Japanese successors, one of whom, Nanpo Shomyo (1235-1309), is a key link in the ongoing succession of the Linji lineage (Japanese, Rinzai) in Japan and now into the global dharma world.

The brilliant Hakuin (1686-1769) was enormously fond of Xutang and it was due to his strong recommendations for students of Zen to become deeply familiar with Xutang’s teaching that I took up the project of translating and commenting on The Record of Empty Hall (Japanese, Kido Roku). I’d found a story of the meeting of Xutang and Rujing, Dogen’s teacher in Complete Poison Blossoms from a Thicket of Thorn: The Zen Records of Hakuin Ekaku (see below for that) and found it inspiring that these two seminal figures actually met. I wondered if in Xutang’s preface for Dogen’s Record there were any clues that the two of them might have met as well.

Spoiler Alert: ah, well, a little.

Then recently, I became acquainted with a wonderful Bukkokuji monk, Kogen Czarnik Osho, who is fluent in Japanese. Eventually, a little light went on and I began pestering him and pestering him until he relented and translated Xutang’s preface, which I refer to in the title of this post as “Xutang’s blurb” due to it’s brevity, as you’ll see below. And then I hammered him with objections to petty details and minor quibbles until he double, triple relented.

So here it is:

Xutang’s Preface for Dogen’s Eihei Goroku

Venerable Giin* brought Japanese Dogen Osho’s Eihei compilation. Looking at this composition, it is profound, and not corrupted by words. His sayings capture Tiantong Rujing Osho’s doctrine of no transmission.** Moreover, this old monk’s daily expressions are all sounds of jewels, standing out and exceptional. Taking this and looking at it, old Dogen’s function surpassed his teacher. Those who will take up these records will follow the change of Lu.***

Great Song, 1265, Spring, March

By decree, written by performing abbot of Jingguo Jingcisi, Xutang Zhiyu

A Few Explanations

* Kangan Giin (1217-1300) seems to have begun his Zen training with the Dharumashu and moved to Dogen’s Koshoji, near Kyoto, and then followed Dogen into the mountains and Eiheiji. He appears to have received transmission from Dogen’s primary successor, Koun Ejo, and then more than a decade after Dogen’s death, took the Eihei koroku to China so that it could be abridged and sanctioned by another successor of Rujing, Wuwai Yiyuan. Upon his return from China, Giin established himself on Kyushu and is regarded as the founder of the Higo Branch of Soto Zen. Click here for more. See Did Dogen Drop and When for more about Giin’s trip to China, including the definitive confirmation of Dogen’s awakening experience.

** According to the notes, the phrase “no transmission” is shorthand for “not depending on words or letters, special transmission outside scriptures” from the verse attributed to Bodhidharma, because the first and last characters are the same.

*** Also according to notes, the phrase “follow the change of Lu” is a reference to a saying, probably by Confucius, referring to old kingdoms during the Spring and Autumn Period in China: “If kingdom Qi would change, it would become like kingdom Lu. If kingdom Lu would change, it would become the Way.”

A General Comment on Xutang’s Preface

Xutang holds nothing back in his praise for Dogen. He equates the transmission from Rujing to Dogen with Bodhidharma’s transmission of no transmission, clearly going beyond lineage affiliation. It seems that for Xutang, like Dogen, the point wasn’t about lineage, but about the buddhadharma. Period. Full stop.

Xutang says that Dogen’s activities of body, speech, and mind are like the jingling of jewels. Now how would Xutang have heard those jewels jingling unless he and Dogen had met? But that’s pretty speculative, so I’ll leave that for you to access.

Xutang also says that the Japanese Dogen went beyond the Chinese Rujing. How’s that for going beyond ethnicity? And also that if a person takes up Dogen’s Record that they will change into the Way, like a dragon that changes at the skeletal level.

That’s one helluva blurb and one helluva promise for a book.

What Xutang doesn’t include is any note about how this guy Dogen was inventing some new Zen school that involved a hostility to zazen-samadhi-koan as well as awakening and instead emphasized a new practice, never heard of before from any of the greatest teachers in Great Song China – shikantaza.

Xutang recognizes Dogen as a peer, as a Zen master, as an awakening being.

The Record of Empty Hall Excerpt

Below you’ll find the excerpt from The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, p. 6-8, that connects the dots between Xutang and Rujing, Dogen’s teacher:

After his enlightenment and acknowledgment as a dharma heir of Yun’an, a twenty-seventh generation successor in China, Xutang went traveling to further refine his awakening. One stop along the way was at Tiantong Rujing’s place. Rujing (1162–1228), the teacher of Eihei Dogen (1200–1253), became the last ancestor in the Caodong lineage, which became the Japanese Soto lineage that continues to this day in Japan and in other countries. In the same way, Xutang, teacher of the Japanese monk Daio Kokushi, turned out to be the last Chinese ancestor in what became the Japanese Rinzai lineage. Little did either know what a generative intersection their relationship would turn out to be.

The connections between Xutang and Dogen went beyond their mutual participation in parallel processes of international transmission between China and Japan. Toward the end of Xutang’s life, he wrote a preface to the collected works of Dogen. Not only that, but a student of Dogen, Tetsu Gikai, may have been the person who introduced Daio to Xutang.

But back to Rujing. Twenty-three years Xutang’s senior, the old buddha did not go easy on the youngster. Hakuin told the story like this:

When Zen master Xutang met Head Priest of Ch’ing-tz’u temple, Rujing said, “Your parents’ bodies are rotting away in a thicket of razor-sharp thorns. Did you know that?”

“It is wonderful,” Xutang replied, “but it’s not something to act rashly about.”

Rujing gave Xutang a slap. Xutang extended his arms, saying, “Let’s take it slow and easy.”

Rujing’s challenge to the young Xutang was about his dharma ancestors’ bodies, those hard-to-pass-through koans, that according to Rujing were lying rotting, unvivified by Xutang’s ongoing practice. It was no small rebuke. Xutang’s response reverberated with the saying of Yun’an’s that had previously so annoyed him: “Take it easy, just remain mindless and unfettered by words.”

Even Rujing’s slap didn’t cause him to turn his head. Hakuin commented on this encounter, saying,

The means employed by these two old veterans are exceedingly subtle and mysterious. Scrutinize them carefully and you will find that Rujing’s question is as awesome as the great serpent that devours elephants whole and excretes their dry bones three years later. Xutang’s reply has the vehement purpose of the evil P’o-ching bird, which seeks to devour its mother as soon as it is born.

Setting aside snakes pooping out the remains of their thoroughly digested noble practice, and an unfilial student that eats its own teacher immediately after awakening, the question for us today is this: How can we get to the rotting bodies of our dharma ancestors so that we might thoroughly embody the truth of Zen before our parents were born?

And then give the corpses a decent burial.

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Ōshō, with the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training, an internet-based Zen community. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, is now available (Shambhala). He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin Katagiri.

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Ōshō, with the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training, an internet-based Zen community. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, is now available (Shambhala). He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin Katagiri.