A preliminary note

After focusing for the last five years on other translating and writing projects, I plan to do more regular posting here at Wild Fox Zen this year. One of the virtues of this kind of writing is that it offers more opportunity for engaging with you, dear reader, in the perfect present. If you have a comment that you’d like to share, you are welcome to do that on Facebook (the Disqus platform offered through Patheos is not optimal imv) – you can find me and these posts shared here.

If you are interested in taking the plunge and working with Tetsugan Sensei and I and our Vine of Obstacles sangha with our innovative methods for supporting householder Zen training, click here. To financially support our teaching practice, including this Wild Fox Zen Blog, click here.

In this post

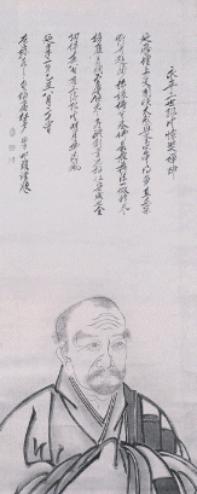

I want to share my enthusiasm for the teaching of Koun Ejō Zenji (孤雲懐奘, Solitary Cloud Strong Heart, 1198-1280), the Japanese Sōtō Zen succession’s second generation ancestor. Old Ejō has been largely eclipsed by his master, Eihei Dōgen Zenji (永平道元 Eternal Peace Way Source, 1200 – 1253), and that’s just the way that Ejō wanted it to go.

However, Ejō was one of the bright lights of a very bright period in Zen, the thirteenth century, so let’s shine a little light his way and simultaneously, I hope, we will be illumined by his teaching. In this post, I’ll provide some background on Ejō, his pivotal awakening experience, one example of his luminous teaching, and then a few notes on his rich legacy.

Why? In addition to illumination, it’s important to know where we’ve come from so that we can clearly discern what the buddhadharma is rather than being fooled by contemporary tendencies to dilute the milk of the buddhadharma with intoxicants, such as that our Zen Way is an easy-going path of faith, an intellectual entanglement, a psychological reframe, a dualistic mindfulness, or by fetishizing just sitting.

Ejō’s life and teaching provide a clear and inspiring example for people today. So let’s get to it.

How Do We Know What We Know About Ejō?

Most of what is known about Ejō comes to us through the Denkōroku (伝光録, Record of the Transmission of Illumination ) by Keizan Jokin Zenji (瑩山紹瑾, Lustrous Mountain Bequeathing Jewels, 1268–1325). (1) It’s a story that has a lot in common with many thirteenth century Zen/Chan masters including pilgrimage, finding an intimate friend, and awakening through the key phrase of a kōan. Yet, Sōtō Zen, according to the Post Meiji Sōtō Orthodoxy, is about just sitting itself as awakening and so most of all these elements might be considered extra. Some might even wonder, is this source about Ejō reliable?

Therefore, before we get into Ejo’s biography, let’s take a short detour to look at the Zen master who gave the talks that became the Record of the Transmission of Illumination, Keizan Zenji. More will be coming your way about Keizan and by Keizan quite soon on this very Wild Fox Zen blog.

Keizan joined the Eihei-ji community when he was eight years old and received monastic vows from Ejō when he was thirteen. His grandmother and mother were both students of Dōgen. So Keizan knew the man he was talking about.

Not only that, Keizan went on to train with at least three of Ejō’s successors, including Jakuen (寂円, Silent Circle, 1207 – 1299), the Chinese student of Rujing who followed Dōgen back from China; Gien (d. 1313) who was one of the scribes for Eihei’s Extensive Record and became the fourth abbot of Eihei-ji; and Tetsu Gikai Zenji (徹通義介, Pervading Clarity Justice Mediator, 1219 – 1309) from whom Keizan received dharma transmission. Gikai probably sat in the assembly at Daijō-ji while Keizan gave the talks which became the Record of the Transmission of Illumination – only fifteen years after Ejō had died. So Keizan not only had intimate access to the details of Ejō ‘s life, his life was surrounded by the old master’s successors.

So don’t you go and say, “Aw, Keizan, that old fibber. He’s just making up that shit about kōan and awakening.”

What is Ejō’s story?

Ejō was born into the Fujiwara clan, a very powerful aristocratic family, as were Dōgen and Nampo Jōmyō Zenji (南浦紹明, aka, Daiō Kokushi,1235–1308) who transmitted the Rinzai lineage of Xutang Zhiyu (虚堂智愚, 1185–1269) to Japan, as well as Ejō’s successor, Tetsu Gikai. At eighteen, Ejō became a monk in the Tendai school, the most powerful school in Japan at the time. He mastered Abhidharma texts as well as Great Calming and Contemplation, by Tiantai Zhiyi (天台智顗, 538–597). It looked like he was headed for a stellar dharma career.

Then, his mother found out he was studying the dharma for fame and gain, and she gave him a good scolding. Taking this to heart, he committed to searching out the true Buddha Way as a simple black-robe wearing monk.

What a good monk! What a good mom!

After the transformative encounter with his mother, Ejō became interested in the new movements that were popping up in the early thirteenth century dharma scene. He first studied with the Pure Land school and then tried a new Zen school, the Daruma-shu, a bunch who were original-enlightenment precept-deniers, or at least that’s what we’re told. Their founder, Dainichibō Nōnin (大日房能忍, d.u.), was a Tendai monk who received a questionable Zen dharma transmission. As the story goes, he sent a couple of his students to China with a letter for the successor of the great Dahui Zonggao (大慧宗杲, 1089–1163), Zhuoan Deguang (拙庵德光, 1121–1203), who then gave Nōnin dharma transmission via monk courier, the two never having met.

A one letter verification! It must have been one helluva letter.

While with the Daruma-shu, Ejō studied with Nōnin’s successor, Holy Man Butchi (佛地上人, Butchi Shōnin) or Kakuan (覺晏, d.u.), who taught about seeing nature (見性, kenshō), but not with kōan – that would come later in Ejō ‘s training when he encountered Dōgen.

Keizan reports, “At one time, they [Kakuan and Ejō] discussed the Heroic March Sūtra. Upon coming to the metaphor of the kalavinka pitcher, where it is said that adding emptiness does not increase emptiness, and removing emptiness does not eliminate emptiness, [Ejō] had a deep tallying. Holy Man Butchi said, ‘How is it that you have completely extinguished the roots of evil and obstructing delusions from beginningless vast kalpas and become liberated from all suffering?’” (2)

Must have been a pretty fine kenshō.

Shortly afterwards, Ejō heard about Dōgen returning from China intent on transmitting the true buddhadharma and thought, “I am no longer in the dark about the essential teachings of the three calmings and three contemplations, and I have already mastered the essential practice of the single gate of Pure Land, but that is not all. I have also sought instruction at Tōnomine Peak [from Kakuen] and fairly well penetrated the gist of ‘seeing the nature and attaining buddhahood.’ What matter [beyond this] could he [Dōgen] have to transmit?” (3)

That is a dandy post-kenshō inflation.

Fortunately, Ejō strutted over to check out this Dōgen fellow. To Ejō’s delight, they talked for several days and found themselves in deep accord. In Zen terms, he’d found an intimate friend (知音), someone with whom there is a closeness that’s likened to a lute player’s playing depending on their intimate friend’s hearing the music.

In Steven Heine’s new biography of Dōgen, he notes that Ejō meeting Dōgen was “like water meeting water or sky meeting the sky.” (4) Not every dharma student is so fortunate to find an intimate friend and so this was quite a big deal for both Dōgen and Ejō. It seems to me that Dōgen’s lute playing for his intimate friend became the Shōbōgenzō (正法眼蔵, The Treasury of the True Dharma Eye) and Eihei Kōroku (永平広録, Eihei’s Extensive Record).

After the deep accord of the first days of their meeting, things changed when Dōgen revealed a rather different perspective. We aren’t told what that entailed. These old texts have a way of leaving out some of the most tantalizing details!

At first, Ejō found himself resistant to Dōgen’s perspective, but then admitted that Dōgen’s understanding was beyond his, so Ejō again aroused the Way Seeking Mind and requested that Dōgen accept him as a student. Dōgen wasn’t in a place to accept students, though, and so told Ejō to wait. And he did. When Dōgen was ready a couple years later, Ejō became one of his first students and his attendant, training under his guidance for the next twenty years, and rarely leaving his side.

Meanwhile, the Daruma-shu became the feeder school for Dōgen’s movement with many of the important figures in early Sōtō having first studied in the Daruma-shu and some even having received dharma transmission from Kakuen, as Ejō himself had done. Indeed, Dōgen may have offered members of the Daruma-shu shelter when they were under attack from other Buddhist sects.

Dōgen and Ejō’s continued closeness was also demonstrated by Dōgen having Ejō serve as the officiant for most ceremonies, including daily liturgy, at Eihei-ji. This is a role normally reserved for the abbot. Dōgen explained, ”

“My life will not last long. Yours will be longer than mine, and you definitely must propagate my way. Therefore, I value you for the sake of the dharma.”

After Dōgen’s death in 1253, Ejō became the second abbot of Eiheiji where he lived and taught for almost thirty more years. What did he teach? Wait for it….

Awakening

Ejō, like many practitioners, seems to have had more than one awakening experience. Keizan, with clear, bright intention, selected the following for his Record of the Transmission of Illumination:

“The fifty-second ancestor, Eihei Jō Osho [aka Ejō], attended Gen Osho [aka Dōgen]. One day, at the time of asking for further instruction, he heard, ‘One hair pierces multiple holes’ – the causes and conditions exactly reflected and awakened.

“That night, bowing, [Ejō] asked, ‘Not asking about one hair, what is multiple holes?’

“Gen smiled and said, ‘Pierced!’

“The master bowed.” (5)

First a few context points:

This awakening occurred at Kōshōhōrin-ji (興聖法林寺, Flourishing Sacred Dharma Temple), near present-day Kyoto, in the middle 1230s, well before Dōgen & Co. abruptly picked up their bundles and trundled up to what became Eihei-ji.

“The time of asking for further” (請益, shōyaku) is a “small meeting” during the monastic day when students meet in front of the abbot’s quarters and can raise issues for the Zen master to address. It appears that another student, or perhaps Dōgen himself, raised this old case where the phrase, “One hair pierces multiple holes,” probably from a koan that involves Shishuang and Jingshan. The full old case is included in Dōgen’s collection of 300 kōans. (6) Notably, the ancient practice container included small group and individual instruction, as is shown by Ejō bowing at night and saying, “Not asking about one hair, what is multiple holes?”

In addition, the binomial that is translated here as “causes and conditions,” (因縁), can also refer to the old case itself. So this could be rendered, “the old case exactly reflected and awakened.”

Does that expression cause surprise or confusion?

Yes, the case and/or the causes and conditions exactly reflected and awakened.

To whom is this happening? There is precise action in this sentence, but no subject! There is just exactly “One hair pierces multiple holes.”

Bodiford’s version, like the other translations I know of, has something advancing and the subject, Ejō, awakening. However, the bare-bones characters can also be read without imputing a self – “the causes and conditions (or the old case) exactly reflected and awakened.”

As for the old case itself, what is the subtle meaning of this phrase, “One hair pierces multiple holes”?

The meaning isn’t about any intellectual speculation or conceptualization. In order to appreciate one hair, piercing, and multiple holes, the causes and conditions of this key phrase must be precisely reflected. This luminous mind becomes the clear mirror that reflects “One hair pierces multiple holes” without any gap, any delay, any qualification, or any metaphor.

One hair is then just completely one hair.

And so Ejō asks the old Buddha Dōgen, “Not asking about one hair, what is multiple holes?”

He might have said, “Body and mind dropped off, dropped off body and mind,” but here it appears as “What is multiple holes?”

What is it?!

Pierced.

Legacy

The most tangible legacy of Ejō are the 700 and some years of practicing awakening by thousands of practitioners in Japan and now in the global Zen culture that all rely on Ejō ‘s piercing. In addition, after the death of the charismatic founder, Dōgen, Ejō took up the difficult task of leading the Eihei-ji community. He completed the buildings at Eihei-ji and the training of the monks who became the next generation of Sōtō teachers, including the already mentioned Tetsu Gikai, Jakuen, and Gien. Another successor of Ejō’s was Kangan Giin (寒巌義尹, 1217–1300) an enormously important teacher who took Dōgen’s Eihei’s Extensive Record to China and then started an important branch of Sōtō Zen in Kyushu, Hijo Sōtō. (7)

In terms of his dharma literary output, Ejō helped Dōgen in all his work during his lifetime. After Dōgen’s death, Ejō finalized versions of The Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, Eihei’s Extensive Record, and Zuimonki (Record of Things Heard). So much of what we consider Dōgen’s teaching passed through Ejō before coming our way. Unfortunately, we have little of his own work.

One text we do have is the luminous Kōmyōzō sanmai, (光明藏三昧, The Luminous Treasury Absorption), written when Ejō would have been eighty years old. The text begins with an acknowledgement that Dōgen already taught luminosity in Shōbōgenzō Kōmyō (光明, Luminous, also translated “Radiant Light”). (8) Ejō says, “I am writing this only because I want to bring out this essential matter further because the practice of the Treasury of Luminosity is the essence of the Buddha Way.” (9)

And so he does, alternating between a demonstration of blissful luminosity with a bright, clear crabby voice of an old man who’s seen a lot and is unabashedly expressing his views, dictating his unvarnished full will and dharma testament, all the while pulling no blows of his staff. More on that below.

In The Luminous Treasury Absorption, Ejō also offers a strong sense of continuity with Dōgen’s teaching and telegraphs this by starting with Dōgen’s title and then adding just two words for his The Luminous Treasury Absorption. The first word he adds is the character 藏, “zō,” the same “zō” as in Shōbōgenzō. “Zō” has a range of meanings, including “treasury,” “matrix,” “embryo,” and “womb.” In Sanskrit, it is “garba” as in tathagatagarbha, usually translated as “the womb of the thus come one.”

The other word is two characters, 三昧, sanmai, a transliteration of the Sanskrit “samadhi” “…which means ‘putting together,’ ‘composing the mind,’ ‘intent contemplation,’ ‘perfect absorption.'”

In general Mahayana Buddhism, samadhi refers to the unification of the mind with its object. In Zen, it also refers to the unification of the state of mind with awakening. In this way, Ejō aligns his text not only with Dōgen’s self-fulfillment absorption (自受用三昧, jijuyū sanmai), but also with the great Sōtō/Caodong tradition through Dongshan Liangjie ‘s (洞山良价, 807–869) jewel mirror absorption (寶鏡三昧; hōkyō zammai).

Dōgen’s Luminous has 2,300 words in one English translation – shorter than this blog post! Ejō, making up for lost time, has 8,500 words in his The Luminous Treasury Absorption. Ejō’s text is similar to the structure of many of Dōgen’s writings in that he freely makes use of Mahayana sutras as well as kōan and sayings from the old Zen masters, followed by brief comments, often reframing the usual meaning of a cited passage.

In fact, in order to demonstrate that The Luminous Treasury Absorption is the essence of the Buddha Way and in alignment with the authentic transmission of the buddhadharma, Ejō cites thirty-three sources, evenly divided between Mahayana Sutras and kōan/sayings of Zen masters. That’s a lot more than most Treasury of the True Dharma Eye fascicles. The sutra citations in The Luminous Treasury Absorption include The Flower Garland Sutra (three references), The Lotus Sutra (two references), and The Vast Inherent Radiance Sutra (two references). Kōan/sayings of Zen masters include those from Bodhidharma, Yongjia, Baizhang, Caoshan, Xuefeng, and Yunmen. Indeed, Ejō takes up the same Yunmen kōan that Dōgen included in his Luminous:

“Yunmen said, ‘Everyone has this luminosity but when they look for it they don’t see it. What is this luminosity?’ As no one could answer, he answered for them, ‘The Monks’ Hall, the Buddha Hall, the Kitchen Hall, the Gate.'”

Here’s a selection of Ejō’s essential message about the essence of the Buddha Way, expressed with blissful luminosity:

“In this luminosity usual people and sages, deluded and enlightened are one. In the midst of impermanence, this luminosity is unobstructed. Forests, flowers, grasses, leaves; humans and animals; large or small, long or short, square or round: all display themselves simultaneously, free of discriminating thoughts or intention. This is luminosity unobstructed in impermanence. Luminosity is its own open brilliance; it does not depend on your mind. Luminosity has no location. When Buddhas appear in this universe, it does not arise with them. When Buddhas cease, luminosity does not cease. When you are born, luminosity is not born; when you die, luminosity does not die. Buddhas do not have more of it; sentient beings do not have less.”

As for Ejō’s crabby old man voice, it is notable that Dōgen tended to direct his ire at teachers in other lineages in the past. Ejō directs his at students in the present and future who practice with mistaken understandings and don’t heed good advice (like his good advice). A few examples:

“Deep practice of the Way requires tireless exertion and confidence in what is true. Unless you join the Lineage of the Buddhas life after life, how can you understand anything that I say at all?”

“Some people look for this [luminosity] as some underlying entity or try to get rid of their thoughts and experiences. They do not understand this hidden essence. Some doubt it all, and go about their business dwelling in the cave of ghosts. Some act like they are diving into the depths of the ocean to count the grains of sand on the ocean floor. Some are like mosquitoes, buzzing against a paper screen.”

“If your practice is based on your own ideas and unquestioned assumptions about what the mind is and what realization is, you are only strengthening the roots of birth and death.”

Finally, both Dōgen’s Luminous teaching and Ejō’s The Luminous Treasury Absorption strongly encourage breakthrough in order to realize luminosity. At the end of Dōgen’s text, he added a colophon stating that the talk was offered at Koshohorin-ji, during the sixth month of 1242, between 12:30am and 1:00am! Dōgen goes on to say, “It has been raining for a long time and raindrops keep dripping from the eaves. What is the radiant light? The assembly must look and break through Yunmen’s words.”

Ejō also calls for breakthrough, for example:

“Tell me, right now: this shitting and pissing, getting dressed and eating … who is it that does this? And what about the sounds of rivers, the colors of the mountains, the coming and going of heat and cold, blossoms in spring, the bright moon in autumn, the thousand changes and numberless appearances? What is it that does this?”

Because the luminosity of this one great life shines through the ages, so do the admonitions of the Buddhas and Ancestors.

(1) Also see Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan, by William M. Bodiford, Zen Buddhism: A History (Japan), by Heinrich Dumoulin, and From Chinese Chan to Japanese Zen: A Remarkable Century of Transmission and Transformation by Steven Heine.

(2) Record of the Transmission of Illumination, by Keizan Jokin, trs. William Bodiford, p. 563-564. “The metaphor of the kalavinka pitcher: This refers to a passage in the Heroic March Sūtra, in which the unreality of the ‘aggregate of consciousnesses’ is explained by comparison to the empty space inside a kalavinka pitcher (a vessel with two spouts pointed in opposite directions, shaped like the mythical kalavinka bird): Ānanda, it is as if someone were to take a kalavinka pitcher, seal both spouts when it is completely empty, and carry it for use as provisions in another country one thousand miles away. The ‘aggregate of consciousnesses,’ you should know, is also like this. Ānanda, empty space like this does not come from over there, and it is not imported here. If it came from over there, Ānanda, then the amount of emptiness originally in the bottle should be preserved, and the amount of empty space in the land where the bottle came from should be reduced. And, having imported it to here, when the bottle is opened, we should see the emptiness pour out. Therefore, you should know that the [notion of an] ‘aggregate of consciousnesses’ is a falsehood. Fundamentally, it is neither conditioned nor self-existent.”

(3) Ibid.

(4) Steven Heine, Dogen: Japan’s Original Zen Teacher.

(5) Trans. Dosho Port.

(6) See The True Dharma Eye: Zen Master Dogen’s Three Hundred Koans, by Daido Loori and Kaz Tanahahsi, Case 85: Shishuang Chuyuan was once asked by Senior Monastic Quanming, “When does a single hair pierce innumerable holes?” Shishuang said, “Ten thousand years later.” Quanming said, “What will happen ten thousand years later?” Shishuang said, “It is you who will pass the examination and excel among people.” Later Quanming asked the same question of Zen master Hongyin of Jingshan [Faji]. Jingshan said, “You personally will have to shine your sandals and harvest the fruit.”

(7) See The Practice of the Treasury of Luminosity, trs, Ven. Anzan Hoshin Roshi and Yasuda Joshu Dainen Roshi. All quotations in this post are from what I call The Luminous Treasury Absorption are from this translation. Also see a version by Thomas Cleary here.

(8) The Buddha of the Pali Canon also had a teaching with the title “Luminous.” See Pabhassara Sutta: Luminous. It seems unlikely that Dōgen knew of this sutta when he wrote his Luminous in 1242, although a copy of the Pali Canon was donated to Eiheiji sometime later and so it may have been known by Ejō.

(9) See Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan, “Giin: The Beginnings of Higo Sōtō,” by William M. Bodiford.

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Sensei, with the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training, an internet-based Zen community. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, is now available (Shambhala). He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin Katagiri. Click here to support the teaching practice of Tetsugan Sensei and Dōshō Rōshi.