What this post is about

Recently, a friend shared a passage from the Shunryū Suzuki Rōshi archive that includes some of Suzuki Rōshi’s momentary thoughts more than fifty years ago about kenshō, householder practice, Sōtō Zen, and Rinzai Zen.

I’ve been writing both here at Wild Fox Zen and at Patreon about One School Zen and have been wondering about how we got here – in our contemporary global Zen, Sōtō and Rinzai lineages seem far apart and each flavor of Zen has some “ideas” about the other. One source for this, of course, is the early Zen pioneers that came from Japan. And Suzuki Rōshi is one of the most influential of those ancestors.

So although this post isn’t really part of the current series that explores the Sōtō ancestors before and after Dōgen, it does have a related theme – if Zen is One School, why don’t more people see it that way?

In this post, I’ll first share Suzuki Rōshi’s comments and then make a few observations as the result of my efforts to understand what he said more clearly.

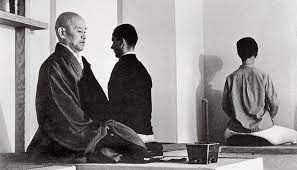

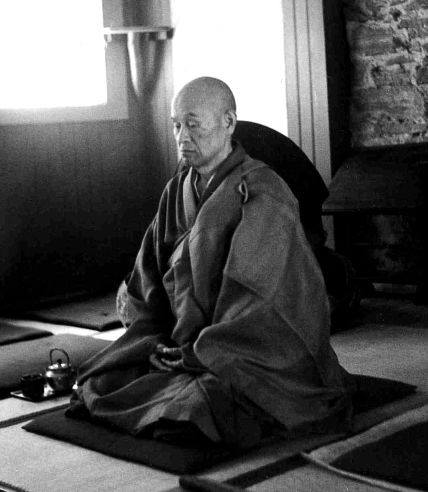

Suzuki Rōshi (July 22, 1971 at Tassajara)

“As you are laypeople, most of the time you have no time to forget about your dualistic life, so dualistic practice goes first. So, for laypeople some practice like Rinzai Zen is maybe better for someone. Rinzai practice is very dualistic, so that will give you some strength to encourage non-dualistic side more and to fight with dualistic ideas until you can forget all about the dualistic way of life even for a moment.

“That is so-called kenshō. But even though you have kenshō, you do not have a Buddhist life completely. You just get a glance of your buddha nature, which is not egoistic. You just experience literally [laughs] a nonegoistic life. But it doesn’t last, because you are so busy and you are deeply involved in usual way of life. That is layman or laywoman practice.

“How, then, the Sōtō way helps lay[people] is to let you follow nondualistic way of life, like Tassajara. Many laypeople participate in our practice, which is not dualistic and which puts more emphasis on nondualistic practice. So, if you follow Sōtō way, even though you do not feel you have entered the non-dualistic experience, more and more your life will be non-dualistic because our way of practice, the way we set up our practice, is according to non-dualistic way of Buddha. That is why we in the Sōtō School put more emphasis on how to eat, how to drink, how to walk, how to work, how to recite sutras. So those rituals set up by Soto teachers are based on a non-dualistic idea.

“So, following a non-dualistic way of life in a Buddhist school, more and more, you will be familiar with non-dualistic life. The Sōtō way, as you may have noticed, is not so dualistic, and we do not encourage students so strictly by working or shouting [laughs]. We don’t use the stick so much. I have one, but I don’t use it as much as a Rinzai master maybe uses it, because our practice is based on the non-dualistic way.

A few observations

The first thing that stands out is Suzuki Rōshi’s interest in working with householders and his acknowledgement that Sōtō monasticism isn’t ideally portable. His prescription seems to be that householders should experience the nondualistic practice of a Sōtō monastery and then “more and more your life will be non-dualistic.”

However, I’m left wondering if for Suzuki Rōshi it was just the old osmosis thing or if there were any specific guideposts. Otherwise, it comes off as rather “faithee” and not about verification (aka, proof), as was emphasized by the old founder, Dōgen. And if it’s gradual, “more and more,” then that’s pretty dualistic, no?

The second standout is how far we’ve come in the last fifty years in appreciating the various schools of Buddhism, let alone other lineage streams within the Zen school. I can’t imagine any contemporary teacher claiming that their branch of Zen is more nondualistic than another branch – and keep a straight face, because, well, come on, that’s again a pretty dualistic thing to put out there! There tends to be a lot of difference within groups designated as “Sōtō” or “Rinzai.”

Third, I’ve read this Suzuki Rōshi passage many times, but I’m still not sure what Suzuki Rōshi’s his main point is. What he says sounds good and I’m left with a good feeling, but in fact, the more I read it, the less clear I am about what he’s saying.

The only specific elements of what Suzuki Rōshi calls dualistic Rinzai practices are working, shouting, and beating. In terms of monastic work practice, if that’s what Suzuki Rōshi is referring to, I don’t see any big difference between Japanese Sōtō or Rinzai in that regard. Monastics in both branches (ideally) work with inspiring one-pointed wholeheartedness.

As for occasionally getting shouted at or beaten, well, how does that help householders? Maybe because these methods can (in the right circumstances) catalyze kenshō. Suzuki Rōshi recognizes (somewhat disparagingly while minimizing the impact) that kenshō can be a toehold in the Buddha’s world. “But even though you have kenshō,” he said, “you do not have a Buddhist life completely.”

Certainly, every pro-kenshō Zen teacher I know would agree. Kenshō, as is often repeated, is the beginning of training, not the end. What the kōan lineages offer, therefore, is a post-kenshō process for opening and applying awakening that is generally lacking in just-sitting Sōtō Zen. Suzuki Rōshi seems to acknowledge the limitation of just-sitting Zen in the above passage.

In my experience, though, I’d like to add that kenshō is often one of the most meaningful and powerful experiences a person can have in this lifetime. Therefore, it baffles me that some contemporary Sōtō Zen teachers (I’m not thinking of Suzuki Rōshi here) minimize the significance of awakening. It’s as if they haven’t experienced kenshō themselves and throw out cautions about something they don’t know. It also seems to me that ranting on against kenshō is like telling a young person not to fall in love, warning that if you do fall in love, then there will be work to do in the relationship. That very post-falling-in-love work is the most fulfilling – and difficult – part of love.

See We Are All This Luminous Mind: The Possibility and Importance of Awakening for more of my view on awakening and the experiences of contemporary householders who’ve had the experience.

As I was saying, there is plenty of shouting and beating in Japanese Sōtō. Dōgen himself recognized that these techniques could help turn the mysterious pivot: “Turning the pivot with a snap of the fingers, a staff, a needle, or a mallet; demonstrating proof by raising a whisk, a fist, a staff, or shouting loudly – this is not done by pondering distinctions and making divisions.”

Suzuki Rōshi also acknowledges that there is beating in Sōtō, so is he saying that a certain amount of beating is nondualistic, but then you reach a point where it becomes dualistic? That is what he says, but I trust that it is not what he really means. Suzuki Rōshi must have known that it is the heartmind that is apparently divided or not and that dualism does not reside in any certain practice or attitude “out there” (because that’s the core of dualism).

So when Suzuki Rōshi says, “Rinzai practice is very dualistic,” what the heck is he talking about? Something that he doesn’t mention directly is kōan work, although in the passage about teasing out dualistic thinking, he says that in Rinzai Zen students “…fight with dualistic ideas until you can forget all about the dualistic way of life even for a moment.”

That quite nicely expresses an aspect of kōan work for many, especially with their first kōan. However, this isn’t the recommended method of kōan work, but a shadow practice that many students take up despite the instruction, as if they can’t help themselves. It may be something that needs to be passed through.

On the other hand, it is true that when working with a kōan and meeting with a teacher, the student either passes through a kōan or they do not – so there’s that sense of dualism, I suppose. But in just-sitting Sōtō there is also doing that is correct or incorrect – tying the ōryōki knot, for example. So if “correct” or “incorrect” is what made something dualistic, just-sitting Zen would have nothing on kōan Zen.

Maybe the old teacher was thinking about kōan zazen specifically and he thinks that such zazen is about sitting and thinking about a kōan and trying to figure it out. Maybe … but that’s not at all what kōan work is about, so in this case, he’d be wrong – setting up an imaginary dualistic practice and then calling it dualistic.

In any case, Suzuki Rōshi’s attitude toward kōan practice was not one-dimensional. He also said, “We don’t know how much our understanding is limited. That is why you have to study kōans. Kōans will open up your mind” (August 24, 1967).

What did Suzuki Rōshi have to say about kenshō, Sōtō Zen, Rinzai Zen, and householder practice?

I’m sorry, it isn’t crystal clear.

In any case, July 22, 1971, was probably a really hot day at Tassajara, and I bet that most of his students were happy just to sit in the zendo and enjoy a nice talk by their dear old Rōshi. He did, after all, have just a bit more than four months to live of this one great life.

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Sensei, with the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training, an internet-based Zen community. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, is now available (Shambhala). He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin Katagiri. Click here to support the teaching practice of Tetsugan Sensei and Dōshō Rōshi.