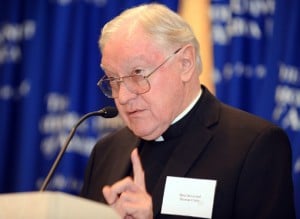

Says who? Says First Amendment scholar, and Auxiliary Bishop of Los Angeles, Thomas J. Curry. As a newbie Catholic, and a layman, I’m not familiar with Bishop Curry, or his studies on this issue. Over at the Catholic University of America, though, he recently gave a lecture on the constitutionality of the HHS Mandate.

His thoughts are more nuanced than any I have seen so far, and they make a lot of sense. Have a look (bold highlights are mine),

The HHS mandate forcing religious organizations to provide contraception for its employees is not unconstitutional. Moreover, the First Amendment should not be considered conscience protection, said Bishop William (sic) J. Curry, First Amendment Scholar.

The First Amendment, he said was “about what the government may not do. It is not about what individuals may do.” Additionally, according to the 1990 court case Employment Division v. Smith, since the mandate does not openly profess to target a specific religion, it is constitutional.

However, Curry, in a lecture entitled “Religious Liberty, Conscience and Contraception,” highlighted how the mandate’s exemption, deemed positive by many conservatives and religious people, violates the First Amendment by defining the term ‘religious organization’ according to government standards. The exemption, in deciding to limit religious institutions to only institutions that inculcate values and consist of people who are tenants of the faith, requires the government to judge who actually follows the tenants of a faith.

The government, Curry is saying, would thus have the power to decide who is and isn’t truly Catholic. This violation would involve governmental involvement outside of their strictly secular limits and would cause them to discern religious matters.

That some facets of the HHS Mandate aren’t unconstitutional shouldn’t surprise you. Think about it for a minute. How many heresies are grounded in truth, for example. All of them, right? But the Church fights against heresy because they take an angle on the truth, to the exclusion of revealed truth as a whole. Now, the HHS Mandate was crafted by lawyers, which is why it has to be tried and weighed by the same, and that parts of it are not in conflict with some aspects of the First Amendment should be shocking to no one. Back to the piece,

Curry, who holds a Ph.D. in History in addition to the education he received as a priest and bishop, explained in detail how the First Amendment and religious freedom relate to the mandate from HHS.

According to Bishop Curry, while the government can legislate law exemptions for the betterment of its citizens, such as in the case of exempting Catholics and Jews from the strictly secular prohibition laws of the 1920s, an interpretation of the First Amendment that allows for conscience rights actually puts both religious and secular matters in the hands of the Federal government.

Curry pointed out that judicially, complications in understanding the First Amendment originate from the Supreme Court’s acceptance of the Blaine Amendments in the 1940s. These amendments, passed by states in the 1870s, were anti-Catholic in nature by banning funding for “sectarian” schools, mainly Catholic schools, but weren’t against the First Amendment because the First Amendment did not apply to states at the time.

However, this outlook has created the language “a wall of separation between Church and State.” These things do not heavily concern Bishop Curry, who points out, in his observation, that the past court decisions on religion support the First Amendment, while the court briefs do not. He used the example of a recent case involving the firing of a Lutheran Minister to prove his point.

Bishop Curry is referring to Hosanna – Tabor vs. the EEOC, above. He is a scholar of the First Amendment, and speaking for myself, I look forward to hearing more of his thoughts on the matter.

Last Spring, when he was at CUA speaking at a symposium, he was quoted extensively on the idea of the “wall of separation” interpretation that has grown as a result of what he terms as misunderstandings over the years. Mark Pattison of the Catholic News Service covered his thoughts thoroughly.

“Religious bodies cannot violate” the First Amendment, (Bishop Curry) said, because it doesn’t apply to the church. “The state may not interfere with the religious affairs of the church but the church is at liberty to interfere in the secular affairs of the state and does so constantly.”

“Jesus did not say that Caesar should separate and arrange what belongs to Caesar and what belongs to God, but the wall of separation interpretation does that,” Bishop Curry said. “The power to separate is the power to control, but the free exercise of religion means precisely freedom from such government control.”

American Catholics, he suggested, should be more assertive in declaring their religious rights under the Constitution. “Catholic commentators have failed to object and have even approved such violations of civil and religious liberties.”

Bishop Curry labeled the Pauline tradition of deference to civil authority “overly influential” during the past decade. It “has blinded Catholics to the trampling of their civil and religious liberties,” he said. Instead, he noted, “we need the counterbalance of the Johannine tradition, of seeing aspects of the great beast in the abuses of government power, especially with regard to Catholicism.”

“Because the Declaration on Religious Freedom of Vatican II came as such a relief to American Catholics in that they felt they were now in harmony with American liberties, they tended to assume that the prevailing interpretation of the First Amendment was truly representative of that freedom,” Bishop Curry said. “It was not.”

Rather, “conferring on government the power to regulate the church and the state and assign them to their proper spheres and to assess what aids or hinders religion is not compatible with the free exercise of religion. Neither is it compatible with the dignity of the human person proclaimed in the declaration,” he added.

“In the aftermath of Vatican II and its rejection of triumphalism, many Catholic commentators, thinking that Catholics had been too much for themselves alone in the past, tended to stop being for themselves at all in the present,” Bishop Curry said. “As a result, the writing of Catholic history has come in many ways to resemble another lost cause, a long sad tale of woe and failure,” with writers focusing on the failure to create “a truly American church.”

But “the reality is altogether different,” he added.

He goes on to mention the American tradition of Anti-Catholicsm, and more. Go read the rest.

I hope to hear more from Bishop Curry in the future as this struggle unfolds. In the meantime, I will be adding his two books to my tall (and ever growing) stack of volumes to read around this issue.Here is what Amazon says about his First Freedoms: Church and State in America to the Passage of the First Amendment, first published in 1987,

Is government forbidden to assist all religions equally, as the Supreme Court has held? Or does the First Amendment merely ban exclusive aid to one religion, as critics of the Court assert? The First Freedoms studies the church-state context of colonial and revolutionary America to present a bold new reading of the historical meaning of the religion clauses of the First Amendment. Synthesizing and interpreting a wealth of evidence from the founding of Virginia to the passage of the Bill of Rights, including everything published in America before 1791, Thomas Curry traces America’s developing ideas on religious liberty and offers the most extensive investigation ever of the historical origins and background of the First Amendment’s religion clauses.

In 2001, he wrote another book whose title should catch your interest as well: Farewell to Christendom: The Future of Church and State in America.

Thomas Curry argues that discussion and interpretation of the First Amendment have reached a point of deep crisis. Historical scholarship dealing with the background and interpretation of the Amendment are at an impasse, and judicial interpretation is in a state of disarray. Here, Curry provides a new paradigm for the understanding and exploration of religious liberty, contending that much of the present confusion can be traced to habits of mind that persist from Christendom and inevitably draw government into religious matters. The First Amendment, however, was meant to be a departure from the thinking that had preceded it for nearly fifteen hundred years. Curry traces much of the current difficulty to the largely unexamined assumption on the part of judges and scholars that the amendment created a right–the right to free exercise of religion–and that the courts are the guardians of that right. The First Amendment is, in fact, a limitation on government and a guarantee that the government will not impinge on the religious liberty that citizens already possess by natural right. Here, Curry shows that the key to finding more coherence between Church-State decisions and the historical meaning and purpose of the First Amendment lies in embracing this understanding of the Amendment as a limitation on government.

Fascinating! It looks like my public library’s interlibrary loan department will be getting a workout soon.