(H/T)

(H/T)

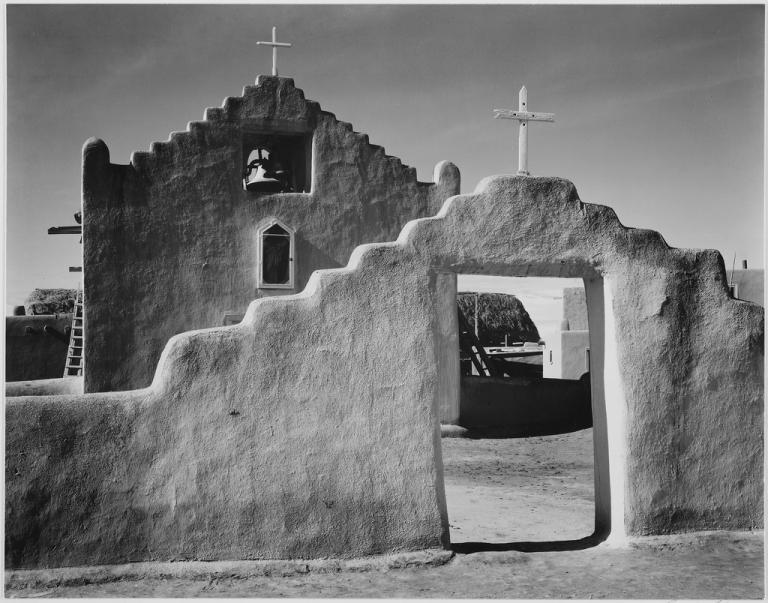

Remember the verse about the narrow gate?

It comes at the very end of the Sermon on the Mount when Jesus says,

Enter through the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and the road is easy that leads to destruction, and there are many who take it. For the gate is narrow and the road is hard that leads to life, and there are few who find it.

Growing up, whenever I heard a pastor preach this passage or another Christian quote it, I had the distinct impression that this verse was supposed to scare the hell out of me.

Literally.

It was (and often still is) a verse that gets invoked as a trump card for demanding conformity to the Christian life – as defined by the person invoking the verse. As I was often told, real Christians don’t smoke or drink or swear or wear comfortable clothes on Sunday because the world does those sorts of things and the world is on the wide road to destruction. But we’re Christians and Christians must go through the narrow gate of strict rules, lots of discipline, and no fun.

Moreover, it seems like we expend a lot of energy today trying to keep the gate as narrow as possible. We fight for orthodoxy and stand up for “traditional Biblical values” and demonize anyone who doesn’t conform to a very narrowly defined understanding of the Christian life. And while not that all of those things in themselves are necessarily bad, in our never-ending battles over rules and beliefs and lines in the sand, we sure seem to end up acting a whole heck of a lot like the Pharisees a lot of the time.

That said, the older I get – and I’m not old at all – the more I’m struck by how curious a thing the Bible actually is.

You read it at a certain point in life at a certain age under certain circumstances and you come away with an understanding of the text that you’re absolutely convinced is what it really means and thus it can mean nothing other than that.

But then you pick up the Bible again and read the same passage at a different point in life at a different age under different circumstances and seemingly out of nowhere you find yourself reading the same words in a totally different way.

At least, such is the case for me and the seventh chapter of Matthew’s gospel.

Call it coincidence, call it fate, call it the hand of God, call it whatever you want but the other day I found myself reading Matthew 7 again for the first time in a long time and I got stuck on Jesus’ words about the width of gates and I began to wonder something I’ve never wondered before about a passage I thought had I already figured out long ago.

Nothing super profound, mind you, just a simple thought.

What if Jesus’ call to enter through the narrow gate isn’t a call to live a life of prohibition? By that I mean, I think it’s still a call to life a particular kind of life, but what if that particular kind of life isn’t a life defined simply by what we don’t do and who we avoid?

I know I could be wrong and since I’m offering an answer to my own question, maybe I am, but it seems to me that the answer to what kind of particular life the narrow gate life really is can be found in what Jesus says next.

Beware of false prophets, who come to you in sheep’s clothing but inwardly are ravenous wolves. You will know them by their fruits. Are grapes gathered from thorns, or figs from thistles? In the same way, every good tree bears good fruit, but the bad tree bears bad fruit. A good tree cannot bear bad fruit, nor can a bad tree bear good fruit. Every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. Thus you will know them by their fruits.

It’s easy to get distracted by that “false prophet” phrase and all the apocalyptic imagery it conjures up, but Jesus’ words were less a future prediction and more of a contemporary criticism of the religious leaders of Jesus’ day. You know, the Pharisees, Sadducees, Teachers of the Law. All those folks who thought they had the narrow gate life figured out and demanded others act accordingly.

But according to Jesus, their tree of life was full of bad fruit.

While that probably comes as no surprise, we shouldn’t forget that Jesus wasn’t just calling out the bad fruit of religious leaders. He called out the rest of the people of God too.

Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only the one who does the will of my Father in heaven. On that day many will say to me, ‘Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in your name, and cast out demons in your name, and do many deeds of power in your name?’ Then I will declare to them, ‘I never knew you; go away from me, you evildoers.’

Ouch.

Kinda puts a wrench in our whole say the Sinner’s Prayer and snag your ticket to heaven formula.

It’s almost like Jesus is saying that all our rules and church attendance and legalism aren’t what the narrow gate life is all about.

Which actually makes a lot of sense when we put all of this narrow gate, false prophet, and Lord, Lord talk in the bigger context of Jesus’ ministry.

It’s no secret that Jesus wasn’t a big fan of the Pharisees, Saducees, and Teachers of the Law. I think they would fit neatly into the false prophet category for Jesus because their legalistic efforts to keep others out of the kingdom made for some pretty bad fruit. Which is why, as well all know well, Jesus was constantly undermining their exclusion efforts by extending grace to people the religious leaders of his day had deemed unworthy of receiving grace because of they way they lived or because of what they believed or simply because of the type person they were at birth.

But here in Matthew 7 we see Jesus calling out not only religious leaders who draw lines in the sands of grace.

He’s also calling out their followers who think they get to heaven by staying behind those lines.

And so by placing all of this talk at the end of the Sermon on the Mount, a message that takes the people of God’s understand of the holy life and flips it upside down, it’s like he’s saying, “You guys are right. The way is difficult and the gate is narrow. You just don’t understand what the narrow gate life is really all about.”

If that’s not the case, if the people of God under the leadership and line drawing example of leaders like the Pharisees were, in fact, living the sort of life God wanted them to live, then Jesus’ words about “not everyone who says “Lord, Lord” make little sense because Jesus would seemingly be rejecting people for doing what they were supposed to be doing – living the narrow gate way of life.

Which is what got me to thinking.

What if the narrow gate life isn’t what we thought it was?

What if the narrow gate life isn’t about don’t do this or don’t eat that or don’t hang out with those people?

What if the narrow gate life isn’t really about exclusion at all?

What if the narrow gate life is about love?

Now, I know that we love to say “Jesus is the narrow gate” and that’s true, but more often than not that’s just a churchy go-to answer we give little thought to and devote even less action towards. Worse, it’s usually nothing more than a way to exclude people because they don’t think or believe or act exactly the way we think and believe and act.

But even if we say the narrow gate is Jesus, aren’t we still saying the narrow gate is love?

After all, wasn’t that the reason he came (“for God so loved the world”), the defining mark of his ministry (the greatest commandment), and the reason he died (“This is how we know what love is: Jesus Christ laid down his life for us”) love?

Absolutely, discipline and abstaining from certain things still matters, Jesus says and exemplifies as much. But if rules and doctrines and things we don’t do are the defining mark of the narrow gate, then at the end of the day we’re no different than the Pharisees and this whole chapter makes no sense.

And worse, the very people Jesus came to extend the kingdom of God to are still left sitting outside the gates with no hope of grace.

“We need to love everybody” may be sound like a cliché copout, but the sort of narrow gate love Jesus is talking about is far more difficult than it sounds. Loving everybody is only easy when we misunderstand love as some sort of passive emotion that takes no action, holds no one accountable, and causes no struggle in our lives.

But real, Christ-like love makes our lives harder, not easier.

Welcoming prostitutes and drug addicts to church brings resentment from the person sitting in the next pew. Serving the poor and the destitute requires tremendous sacrifice. Even being a parent can’t test the limits of love when a child appears more frequently in criminal court than around the family dinner table. And we all know too well the battles that rage the moment we refuse to exclude and condemn the LGBT community.

Which is why Jesus’ talk about the narrow gate life at the end of a sermon defined by love and grace should challenge any notion that calling the people of God to love is an easy way out from a life of rules and strict discipline. For if Jesus is right, then loving the unlovable and giving grace to those who don’t deserve it is actually a much harder way of living than following all the rules and believing the right things.

It is, as Jesus himself demonstrated, a way of life that leads through the cross.

Which is why I think few find the narrow gate because the life of radically inclusive love Jesus calls us to is really hard to live out.

Few find their way through the narrow gate, not because few are invited by God, but because it’s easier to draw lines in the sand and decide who’s going to hell than it is to love those people we think are going there.

In other words, the gate isn’t narrow because God wants fewer people in the kingdom of God.

It’s narrow because so many of us have such a hard time accepting just how wide God wants the gate to be.