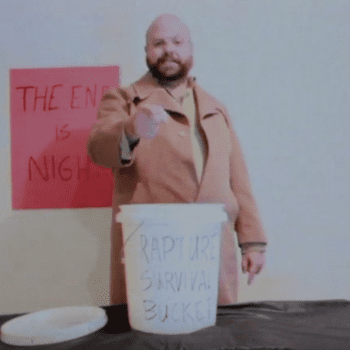

(Credit: Tommy Clark, Flickr Creative Commons)

(Credit: Tommy Clark, Flickr Creative Commons)

I usually loathe conversations about who’s going to heaven and who’s not.

Mostly because it’s never really a conversation about who’s going to heaven. It’s just an opportunity to damn people we don’t like to an eternity in hell, while assuring ourselves of our own place mansion in paradise.

But I’ve been watching a show called First Peoples on PBS and it really got me to thinking and that thinking got me to asking questions whose answers don’t fit so well into the traditional Christian model of eternity that I was taught as a child.

If you haven’t caught an episode of First Peoples, I highly recommend it. It’s a look at how humanity – homo sapiens to be specific (and yes, that actually matters, but more on that in a minute) – first spread across the planet. It’s the kind of show Ken Ham would hate, which means you should love it.

Anyway, the show was eye-opening me for two reasons.

First off, I honestly didn’t realize how amazingly complex the human evolutionary tree really is. I mean, I knew that the famous picture of monkeys evolving directly to humans isn’t right and I knew there were other branches of humanity like homo erectus, but until I watched the show I never really realized there were so many human species (more than a dozen!) and it didn’t really click that we (homo sapiens) lived alongside side of some of them and even interbred with them for tens of thousands of years.

It’s that last thing – the tens of thousands of years – that really got my mind to wandering. Although there is some debate about which remains are those of the most ancient modern human, paleontologists pretty much agree that modern humans began appearing around 200,000 years ago. But even if we go with a much younger set of fossils, we’re still left with around 90,000 years of human history.

Which, in turn, means we’re left with tens of thousands of years before even the earliest traces of the Judeo-Christian faith begin to appear.

As a Christian, that presents a big problem for the idea that only people who declare with their mouth, “Jesus is Lord,” and believe in their heart that God raised him from the dead will be saved.

To be fair, this has always been a touchy subject for Christians. Even those who are adamant that a verbal confession of faith is necessary to avoid eternal flames have to deal with God’s people (Jews) in the Old Testament. The work around for that problem, of course, is that Jews were/are part of the Old Covenant and that their salvation is secured by Jesus, meaning the atoning work of the cross flows both forward and backward in time. This idea is supported by the same Paul who famously said those aforementioned words about declaring Jesus is Lord and believing in your heart and I fully concur with Paul’s theology on this point (about the flow of the atonement).

So there’s a good chunk of the Church today (particularly evangelical Protestants) who are totally ok with the idea of Jews joining them in heaven.

Space is even made a lot of times for that hypothetical person who grew up on a desert island and never heard about Jesus whose salvation we all worried about in youth group. But if the fossil record is right (and it is, so please don’t bother flooding my comment section with Answers In Genesis nonsense), then there wasn’t just one hypothetical dude on an island who didn’t get a chance to hear about Jesus. If the fossil record is right, then there were tens of thousands of years worth of people who lived and died long before Christianity or even Judaism was a thing.

So, what do we do with them?

(And what do we do with the other strains of humanity? And what about neanderthals?)

Do they get to go to heaven since they not only never heard about Jesus, but they never even heard about Abraham or Moses or Noah either?

And if they don’t, if being part of the Old Covenant or confessing Jesus as Lord is the price of admission for heaven, then what does that say about God? In other words, what kind of God gives live to countless people for tens of thousands of years only to doom them to an eternity in hell because they never have any kind of a chance at accepting the free gift of salvation? And if that free gift of salvation really is dependent on saying the right prayer, what does that say about our own role in salvation? For all our talk about faith alone, given all the emphasis we place on a confession of faith, it sure sounds a lot like salvation is almost wholly dependent on what we do and the only thing we have to do is say magic words that bind God to our will.

But for the sake of the argument (and because even the most conservative Christians I know usually agree that God wouldn’t damn the hypothetical island man to hell), let’s assume that God doesn’t send ancient people to hell since neither Judaism nor Christianity would be a thing for a bazillion years.

What do we do with more contemporary people, the folks who did live during the time of the Old Testament or even the New Testament but never had the chance to accept the free gift of salvation because the folks writing the Bible didn’t even know their corner of the world even existed…and vice versa. Do the countless Hindus living and dying on the Indian subcontinent for centuries while Abraham and Moses and David and Paul were doing their thing on the other side of the world go straight to hell because they weren’t part of the Judeo-Christian tradition they had never even heard of?

Ok, maybe we can put them in the same camp as the hypothetical desert island dude. I’m sure most rational Christians, no matter how adamant they might be about a trip to the altar, wouldn’t damn them to hell for their ignorance. But let’s push this thing a little further (cause my pondering didn’t stop when First Peoples went off of the air).

We seem to be ok making space for temporal and geographical isolation when it comes to salvation, but what about cultural isolation?

It’s hard to understand the power of cultural isolation if you’ve never travelled far from home. But if you have, if you’ve had the opportunity to get out and see some of the world, then you know how powerful cultural isolation can be. You know how difficult it can be, not only to change and accept something new, but to even give the slightest bit validity of to different food, different dress, different ideas, different religion. If you’ve only ever grown up around other Christians, it’s easy to say “Well, you heard about Jesus and it’s your fault if you didn’t accept him as your savior.” But if you only ever grew up around other Muslims, for example, just the opposite would be true. In that cultural bubble, the very idea that Jesus would be anything other than a prophet would be blasphemous to you.

So, what do we do with folks like that (whether they be Muslims or Buddhists or Aboriginal or whatever)? Is their cultural isolation really that much different than the temporal or geographical isolation we’re willing to make space for in our theology?

And if so, why?

Now, before you start ranting in the comments about there only being one way to Father, let me stop you and say I completely agree.

However, I also believe that the atoning work of Jesus is efficacious beyond our wildest imagination. It has to be if it’s going to save someone like me and it has to be if it’s going to save someone who lived 90,000 years before God was born in a manger.

I guess I’m a little like C.S. Lewis in that respect.

I’m really weary of putting limits on who’s in an who’s out.

If you’ve read The Last Battle, then you know what I’m talking about. When the heroes of the story get to the new Narnia (heaven), they meet someone they never expected to see there: a young man named Emeth who during his life had worshiped the rival god Tash. Even Emeth is shocked to be there, declaring to Aslan (God), “I am no son of thine, but the servant of Tash.” In response, Lewis (speaking through Aslan) makes one of the most scandalous theological assertions in the history children’s literature,

“Child, all the service thou hast done to Tash, I account as service done to me.” Then by reasons of my great desire for wisdom and understanding, I overcame my fear and questioned the Glorious One and said, “Lord, is it then true, as the Ape said, that thou and Tash are one?” The Lion growled so that the earth shook (but his wrath was not against me) and said, “It is false. Not because he and I are one, but because we are opposites, I take to me the services which thou hast done to him. For I and he are of such different kinds that no service which is vile can be done to me, and none which is not vile can be done to him. Therefore if any man swear by Tash and keep his oath for the oath’s sake, it is by me that he has truly sworn, though he know it not, and it is I who reward him. And if any man do a cruelty in my name, then, though he says the name Aslan, it is Tash whom he serves and by Tash his deed is accepted. Dost thou understand, Child?” I said, “Lord, though knowest how much I understand.” But I said also (for the truth constrained me), “Yet I have been seeking Tash all my days.” “Beloved,” said the Glorious One, “unless they desire had been for me thou wouldst not have sought so long and so truly. For all find what the truly seek.”

Somehow conservative Christians overlook this bit of apparent heresy in their outpouring of love for C.S. Lewis. But despite it’s apparent heresy, I think Lewis’ imaginative snapshot of heaven is actually profoundly insightful, incredibly hopeful, and surprisingly deeply Christian.

For Lewis, salvation is still found exclusively in Christ (Aslan), but that salvation isn’t limited by a confession of faith or even by a confession of another faith. Apparently borrowing somewhat from Matthew 25, Lewis makes the argument that there can be only one Truth, only one Object of our desire, only one Source of goodness, and if we are seeking that Truth in both heart and life, then our temporal, geographical, and even cultural context don’t really matter.

Like, I said, it’s an incredibly scandalous claim for most Christians today, but it actually flows naturally both from scripture and from our own appeal to natural theology and the grace of God when accounting for hypothetical desert island people. After all, in Matthew Jesus reminds us that at the end of all things, confessing “Lord, Lord” doesn’t guarantee a ticket to heaven. Instead, he will turn to each of us and ask “I was hungry. Did you feed me? I was thirsty? Did you give me something to drink? I was naked. Did you clothe me? I was sick and in prison? Did you come and take care of me?”

Whether we want to admit it or not, the answering of those questions is not dependent upon time or place or even knowing the name of Jesus.

In other words, if what Jesus tell us about Judgment Day in Matthew 25 is true, then C.S. Lewis’ vision of heaven isn’t that far off. Which means when we get to heaven, there’s a good chance we’re going to look around and see people we didn’t expect to be there.

For that, I say “Thanks be to God.”

Not because I don’t value the particularity of the cross and resurrection, but because I very much do.

Because in that atoning work, I see love that defies expectation and grace that shatters the limits we try to place on it to reach out and redeem every moment, every corner, and every culture in creation.