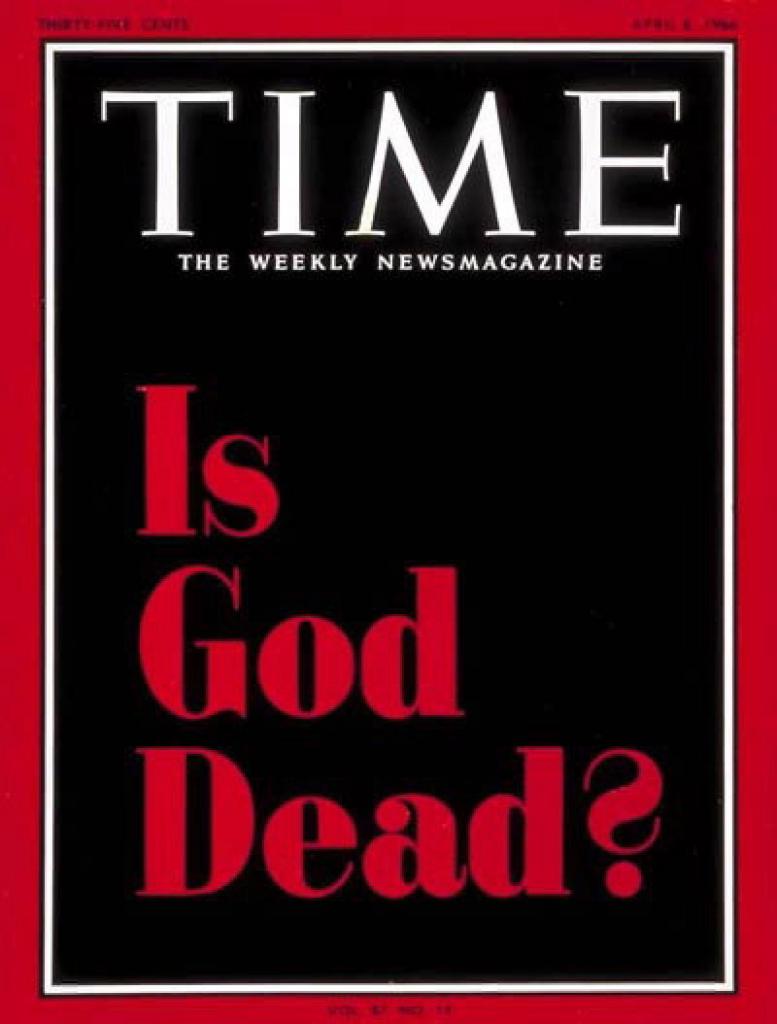

On April 8, 1966, Time magazine created an uproar with a stark, black and red cover that asked “Is God Dead?”

Laity and clergy alike were outraged.

Time received somewhere around 3,500 angry letters to the editor, the most it had ever received for a single article. The idea that God could die was outrageously unthinkable to some and outright blasphemy to others. Which was incredibly ironic considering the day Time published its infamous edition.

April 8, 1966 was Good Friday.

The day God died.

We don’t usually speak about Good Friday in such a provocative way. Instead, we talk about the death of Jesus. Doing so may not seem like a big deal on the surface, but there’s a subtle heresy at play. In speaking of the death of Jesus on Friday, we – whether intentionally or not – acknowledge that the man from Nazareth died, but we protect God from any real suffering, let alone death. While the idea of God being incapable of suffering, much less death, may seem like orthodoxy 101, such a separation of Jesus’ human and divine nature is an ancient heresy known as nestorianism.

Actual orthodoxy declares that Jesus was/is “truly god and truly man,” and therefore his human and divine nature are inseparably intertwined.

This is easy enough to accept when Jesus is hanging out with his disciples doing cool stuff like walking on water and raising people from the dead, but when it comes time to talk about the crucifixion, our insistence on the dual nature of Christ conspicuously become less insistent.

The idea that death could enter into the life of God is simply too scandalous.

We need God to be above that, bigger than that, more powerful than that.

God needs to be Superman times a thousand – invincible, all powerful, and immortal – or how else could God be God?

And yet, as the German theologian Jürgen Moltmann reminds us, it wasn’t just a man from Nazareth that hung on the cross.

It was God.

When the crucified Jesus is called the “image of the invisible God,” the meaning is that this is God, and God is like this. God is not greater than he is in this humiliation. God is not more glorious than he is in this self-surrender. God is not more powerful than he is in this helplessness. God is not more divine than he is in his humanity. The nucleus of everything that Christian theology says about ‘God’ is to be found in this Christ event. – The Crucified God, 205

The One who hung on that tree so long ago wasn’t just a poor carpenter from a backwater town. It was the Lord of all creation. It was the One who said “Let there be light” that was abandoned in the darkness. It was the One who breathed life into dirt who took his last breath on that cross.

It was God who died on the cross on Good Friday.

That doesn’t mean God ceased to exist anymore than we cease to exist when we die, but make no mistake.

God died on Good Friday.

And it’s a scandal we still struggle with today, not just because of what it says about God, but also because of what it says about us and the life we are called to live as followers of a crucified God.

It’s a scandal of disappointment and embarrassment

A crucified God is a total and complete rejection of the John Wayne Jesus we crave in American Christianity. The kind of super manly, guns a-blazing action hero we fetishize in so many corners of the American church is nowhere to be found on the cross. What we find instead is a humble carpenter who rides into town on a donkey, only to be arrested, beaten, and stripped of both clothes and dignity before ultimately being put to death in the most humiliating way possible.

For a Church that is increasingly insecure about its eroding power and influence in the world and desperately wants to portray Jesus as an über-manly hero who stands ready to lead the charge as we vanquish our enemies and wrestle control of the world from their cold dead heads, it’s disappointing, uncomfortable, and embarrassing to be confronted with the truth that we worship a crucified God who said “no” to conquest, choosing instead to die naked and alone for the enemies we seek to vanquish.

It’s a scandal of unwanted inclusion

We may hang crosses prominently in the front of our churches, but the cross has become a sanitized symbol that makes few, if any demands on our lives.

Though we may revere it as an important symbol, we have forgotten that,

The symbol of the cross in the church points to the God who was crucified not between two candles on an altar, but between two thieves in the place of the skull, where the outcasts belong, outside the gates of the city…It is a symbol which therefore leads out of the church and out of religious longing into the fellowship of the oppressed and abandoned. On the other hand, it is a symbol which calls the oppressed and godless into the church and through the church into the fellowship of the crucified God. – The Crucified God, 40

While we sanctify discrimination in the name of religious freedom, the crucified God declares that God stands with the outcast and abandoned, even and especially when they have been cast out and abandoned in the name of God.

It’s a scandal of radical self-denial

The crucifixion of God is a visceral reminder that the cross is the way of Jesus. There is no Christianity without a crucified Christ and therefore there is no discipleship without picking up our own cross and all the suffering and loss that comes with it.

But radical self-denial and painful self-sacrifice has no place in a me-centric society or in a Church which has realized that biblical weight loss strategies, financial peace, and beating the drums of theological war (and actual war) are all far more effective at filling the pews than calling people to live a cruciform life.

And so, the identity of the one hanging on cross remains a scandal today.

Not so much because we can’t agree on the theological nuances of hypostatic union, but because we still can’t accept a crucified God whose power is made perfect in weakness.

Because we don’t want to embrace unwanted neighbors, let alone serve them in any way.

And because as much as we may preach self-denial, actually living a self-sacrificing life that puts others’ needs before our own is simply too much to ask.

The latter half of this post originally appeared in a Good Friday reflection I wrote a couple of years ago.

(

(