(H/T)

While my father-in-law was in town last week we caught up – or I caught up, he had already seen it – on the season finale of Cosmos.

It fitting fashion, Neil deGrasse Tyson ended the first season of his revamped version of Carl Sagan’s Cosmos with Sagan’s own now famous pale blue dot monologue.

But before cutting to the credits, Tyson added a few thoughts of his own that I thought the church would do well to listen to.

Question Authority. No idea is true just because someone says it is. Think for yourself.

Question Yourself. Don’t believe anything just because you want to. Believing something doesn’t make it so.

Test Ideas by the evidence gained from observation and experiment. If a favorite idea fails a well designed test, it’s wrong. Get over it.

Follow the evidence wherever it leads – If you have no evidence, reserve judgement.

Remember you could be wrong.

I realize it’s more than a bit ironic to suggest that the church should take these words as a lesson on faith since there is at least the implicit notion behind Tyson’s words (given his own views on religion) that such a path should lead a person away from faith.

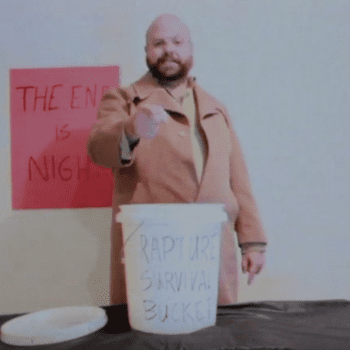

But given the fundamentalism and fear which have become so pervasive in the church today that few of us even recognize it unless it’s standing on a corner with a sign protesting a funeral, I think anyone who believes their faith is really worth believing in should heed the words of Neil deGrasse Tyson.

Why?

For starters, he highlights an important problem that has plagued the faith for centuries and continues to exist today albeit in sometimes more subtle, though no less nefarious ways. I’m talking about tyrants in the church, both those in positions of ecclesial authority and those with popular authority who demand unquestioned obedience to their version of absolute truth. But, as we all know too well, too often the only thing absolute is their desire to damn anyone to hell who disagrees.

While Jesus may have believed that the truth will set us free, we routinely see these despots of dogmatism use the truth – or their version of it – as a means to keep people in bondage.

If we are ever to be freed from the shackles of dogmatism and legalism, it will only happen when find the courage to follow in the footsteps of Jesus and Paul and Luther and countless others who boldly questioned authority, understanding that no matter the Bible verse that might be used as proof text or how strong a demagogue’s rhetoric might be, nothing is true just because some says it.

But even then we must be on guard against ourselves.

Emotions can get the best of us and our passions can prevent us from the sort learning and growing that is critical for a healthy faith. Learning and growing require us to admit that sometimes we’re wrong – even about important things. If we weren’t ever wrong, then there would be no need for growth and, among other problems, we would be left explaining why we don’t need to grow in wisdom, but Jesus did.

Which is why we must remember that strong, passionate faith doesn’t make Christianty true.

But that’s ok, because that’s what makes it faith.

And just as importantly, acknowledging our capacity to be wrong – particularly when it comes to declaring what the Bible teaches – should keep us humble in our strong convictions.

Humble in the knowledge that, as Tyson says, believing something doesn’t make it so.

Now there are obvious limitations in heeding Tyson’s advance. For example, there is no test to prove or disprove the existence of God. But while we may not be able to test that sort of claim, we can test whether or not our theology and concept of the Christian life is actually Christ-like.

In other words, if we claim that we’re being loving and yet the people we say we’re loving are left hurt, ostracized, and abandoned, then we can test our claims of being a loving people against the way people left their encounters with Jesus and, hopefully, realize that we might not be acting quite as loving as we like to think we are.

So while we might not be able to test the existence of God, we can compare the results of our way of living and loving with the way Jesus lived and loved and if we fail the test of Christ-likeness, then we need to admit when our theological rhetoric is wrong….and get over it.

Which leads us to what is perhaps the scariest part of Tyson’s advice for many of us in the church – the call to follow the evidence wherever it may lead.

I think many of us are worried that following the evidence will lead a person to atheism. To be honest, I think some of us should be afraid of this possibility because as people begin to question the sort of God some of us believe in, they’ll probably leave and never look back.

For example, when we preach a God who directly violates the very laws of science we also claim God wrote or proclaim a God who arbitrarily kills some people and damns others to hell for His glory, then we should be worried that questioning that sort of God will lead people down a path that ends in the abandonment of faith. After all who could and who would want to believe in such a God?

However, if we’re as confident that Christianity is true as we claim to be, then we should have nothing do fear about where the evidence will lead.

No question or path of inquiry should be off-limits.

In fact, we should be encouraging people to ask the tough questions and follow the evidence because we should be confident that the conclusions they ultimately reach will be that Jesus really is Lord.

In truth, our dogmatism and fear of questions only reveals a lack of confidence in the things we claim we’re most sure of. For if we really had the confidence of faith we claim to have, we wouldn’t feel the need to demonize people for asking tough and even embarrassing questions because we would have nothing to hide.

Finally, the last lesson Tyson offers might be most important of all, for there may be nothing more fundamental that we struggle with in the church today than admitting that we’re wrong.

It starts with our insistence that we’re just telling it like it is and preaching the God’s honest absolute truth directly from the Bible. But while we might think we’re preaching absolute truth and just telling it like it is and even though we might have the choir singing our praise behind us because they are just as disinterested in difficult questions and the complexities of real life as we are, the real truth of the matter is that it’s our version of the absolute truth that we’re preaching and it’s often absolute only in the sense that we absolutely believe it’s true and absolutely won’t stand to have anyone disagree. If we’re going to claim otherwise – that we are in fact preaching the unfiltered and unadulterated absolute truth – then we must admit that we’re taking a position above what even the Biblical writers claimed to know, that is to say, we believe we are seeing through a mirror clearly.

Now, admittedly, our addiction to absolute truth is a tough habit to kick. When conviction gets mingled with the uncertainty that comes along with faith, we tend to retrench in our sense of surety rather than admit our limited knowledge. And that’s a tough trench to climb our way out of.

I’m also keenly aware that by following Tyson’s (unintentional faith) advice we won’t suddenly convert the world to Christianity.

But that’s ok, because we’re not called to convert anyone anyway.

We’re called to make disciples and unlike making converts, both making disciples and being a disciples requires humility, a passion for learning, and a willingness to allow people to ask questions no matter how tough those questions might be or uncomfortable their answers might make us.