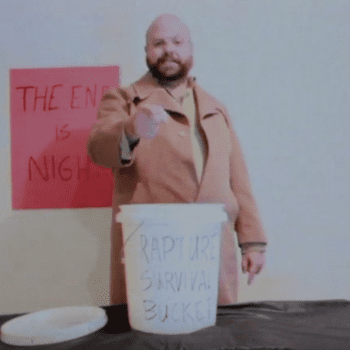

(H/T Michal Kasprzak, Flickr Creative Commons)

(H/T Michal Kasprzak, Flickr Creative Commons)

I get angry with God sometimes.

Actually, that’s not true.

If I’m being really honest, I get angry with God a lot.

When I hear about the atrocities committed by ISIS or the needless starving of millions or priests abusing children or babies being born only to die from some genetic defect I get angry at God.

I get angry because I believe in a God who is worthy of being called God.

I believe in a God who can act in history because God has acted in history. So, I get angry when God chooses not to act to lessen the pain and suffering that saturates the earth.

Now, when I say I get angry with God, it’s not the sort of anger I feel when I get stuck in line at the grocery store because the person in front of me feels compelled to count out exact change while arguing with the cashier over half a dozen expired coupons.

I’m talking about a holier form of anger.

I saw something once that said “anger is just love disappointed.” Though there is more than just disappointment involved for me, I think that sentiment does capture the heart of the sort of anger with God that I’m talking about. I’m profoundly disappointed, heartbroken that the God I love – the God who says He loves me and everyone around me – doesn’t do more to stem the tide of evil in the world.

So, I get angry.

I get angry because I love.

I’m guessing you get angry with God sometimes too.

I think all of us get angry with God at one time or another. Unfortunately, few of us are willing or able to admit it because we’ve been conditioned by a million praise songs and a thousand turn or burn sermons to think that the only emotions we’re allowed to have towards God are adulation and gratitude.

Ironically, we love talking about how much we want an authentic relationship with God, but when it comes to the messiness that accompanies every real relationship we tend to gloss over all that hard stuff with lots of mostly empty platitudes about “just trusting in God” and “letting go and letting God be God.”

Never mind that letting God be God could be an invitation to have our families and everything we own totally wiped out (see: Job), the truth is there is no virtue or holiness to be found in ignoring the problem of evil by hiding behind one-liners about “just having faith” or “loving God anyway” or “it’s all part of God’s plan” or the even more perverse notion that “suffering gives God glory.”

I don’t know how to say it more clearly than this: Telling someone who suffers that God wanted to them to suffer is not just insensitive or theologically dense.

It’s blasphemy.

Yes, we can and should proclaim the hope of the Second Coming, but to completely put off our expectation of God’s acting in response to evil until the eschaton is to silence the prayer of our Lord that Thy will be done (which if Eden and Revelation tell us anything it’s a will that desires no evil or suffering) on earth as it is in heaven.

In other words, we should expect a loving God to act in response to evil, not only because God has done so in the past, but because God has promised to continue to do so in the present.

Which is why when God doesn’t act, our broken hearts should make us angry.

But is it ok to be angry with God?

Well, if the Bible is going to be our guide, then I think the answer is unequivocally “yes.”

The story of God’s people does nothing to hide the fact that God’s people get angry with God. From Cain to Moses to Jonah to the Psalmist to Ananias and countless others in between, the Bible is riddled with the accounts of people who get angry with God and a God who responds with a listening ear.

Take the prayer of Jeremiah for example.

You deceived me, Lord, and I was deceived;

you overpowered me and prevailed.

I am ridiculed all day long;

everyone mocks me.

Whenever I speak, I cry out

proclaiming violence and destruction.

So the word of the Lord has brought me

insult and reproach all day long.

Not exactly the sort of prayer you typically hear at church. But it’s an important moment of raw honesty that demonstrates not only the frustrations even the holiest among us have, but also the willingness of God to listen to our cries.

Of course, if you’re anything like me, you’re so conditioned to always feel joy and thanksgiving toward God that you get a little panicky when you hear someone like Jeremiah lash out at God. You worry that lighting could strike at any moment. But God has never zapped anybody into oblivion because they got mad at Him. If the Bible is to be trusted, then God’s response to our anger isn’t wrath. It’s compassion.

But what about Paul’s words in Romans 9?

“But who are you, a human being, to talk back to God?”

Paul may be borrowing from the book of Job when God famously asks Job who he is to question God.

Well, we are the people of God, that’s who.

We are God’s creation with whom God has entered into covenant, the creation God has made promises of hope to and claims of being loving. If Paul really believed that we shouldn’t get angry with God, he would have had to abandon his own Jewish scripture, something the self-professed devote Jew would never do.

Think about it this way: if we adopt a dog as our family pet, we have certain obligations to that dog to care for it. That doesn’t mean we’re obligated to make sure it never feels pain, never gets sick, and never feels lonely. But if we leave our dog locked up in a cage to starve to death or otherwise abuse it, we can expect to find ourselves in jail.

If we are obligated to care for pets we merely adopted, but had no hand in creating, how much more commitment does God have to us who He created out dust, breathing into the mud the breath of life while bestowing us with His divine image?

Which is why I wonder if we can even be Christians and not get angry with God.

I realize that probably sounds pretty strange, but bear with me for a moment.

You see, it’s the problem of evil that spurs the moments in which I get angry with God. But within the problem of evil there is another subsequent problem for those of us that choose to believe in God despite the tension.

I’m talking about the problem of Jesus.

You see, Jesus seriously complicates the problem of evil for Christians.

Jesus stands as incarnated proof that God cares about creation, that God doesn’t want to see His people suffer, and is doing something about all this evil around us. Moreover, in Jesus we hear the call of God to go and do likewise, to go and do our part to alleviate the suffering of the world by feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, giving water to the thirsty, caring for the sick, visiting those in prison, and loving our enemies.

And yet there is still a profound amount of suffering in the world.

Which leaves us with a conundrum.

If both loving others and belief in a miracle working, death conquering God are core components of our faith, are we not in some sense compelled to be angry at God for continuing to allow so much wasteful suffering and pain?

To put it another way, if we believe in a God worthy of such a title, yet look around at a world filled with needless suffering and feel not even the slight bit of anger at God because He chooses not to act, then are we really worthy of bearing the title of Christian, the name of followers of one who was so grieved by the suffering of others that he sought to take it all upon himself so that it might end forever?

That is to say, if we are not grieved and angered over the plight of our neighbors, do we really love one another?

Again, I know the idea that Christians should ever be angry with the God who saves them sounds a bit strange. But a fundamental part of our faith is our love for the One for whom nothing is beyond His ability to heal and redeem. So, when we look around and see so many in need of healing and so much in need of redemption, how can our love not help but be disappointed?

How can we not get angry with God?

Now let me be clear, this is not about choosing being either love or anger. Like in any relationship, there is room for both. Even though we may get angry with God, there is also space for a faith that hopes in spite of what we see that one day God will indeed wipe away every tear from every eye.

But if the life of Jesus is the good news that God can and is doing something about the problem of evil, I think it’s only natural that we would get angry when we look around and don’t see God doing more to alleviate the pain of so many.

In fact, I would go so far as to say that not honestly and openly confronting the pain and frustration people feel because the God they worship could act but doesn’t, is the very opposite of the sort of compassion and love for others that Jesus embodied.

Which is why I so often find myself protesting to God.

I don’t mean I go to church and hold up picket signs.

I mean cry out to God to do more.

I cry out to God to be the loving and healing God He has revealed Himself to me.

I protest.

My protest stems from a place of anger, a place of love disappointed. It’s a call for God to act, to be faithful to His creation because I believe God is capable of doing so. My protest is not about bearing a grudge or living a bitter life. It’s about following in the footsteps of our biblical fore-bearers and holding God to His promises.

I believe the Bible reveals a God who wants us to feel free to be as honest about how we feel as we would in any other relationship. And if authentic relationship with God is really something we seek, then anger will sometimes be a part of it.

But that’s ok.

In fact, it may be a really, really good thing.

You see, the Bible also reveals a God who is moved to act by the cries of His people.

A God who is moved by protest.