(Credit: JSTOR Daily)

(Credit: JSTOR Daily)

I have stage 2x Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

The x means the cancerous tumor in my body is considered “bulky.”

Per my doctor’s prescribed course of treatment, I will undergo 4-6 months of chemotherapy, followed by a month of radiation. If all goes to plan, at the end of my treatment I will walk away from all of this cancer free and go on to live an otherwise normal life.

It’s nothing short of a miracle because, you see, the curing of my cancer is really just an accident.

I mean no disrespect to my doctors or nurses or the researchers who developed my cure, but the fact that I get to walk away from a disease that has taken the lives of so many is ultimately an accident of my birth.

I was born in 1983 in the United States to a middle class family. 33 years later, still living a middle class life in the first world, I was diagnosed with stage 2x Hodgkin’s lymphoma and became the beneficiary of good insurance and medical advances I had no hand in developing that will do nothing less that save my life.

Had I, instead, been born in 1859, I would be dead.

Maybe not today and maybe not tomorrow, but eventually, without treatment the cancer would spread to other parts of my body and/or the tumor would continue to grow, continue to press on my esophagus until I could no long eat or breathe and I would die.

It wouldn’t be my fault.

It would just be the accident of my birth, an accident of when I was born and under circumstances that didn’t allow for even the possibility of a cure.

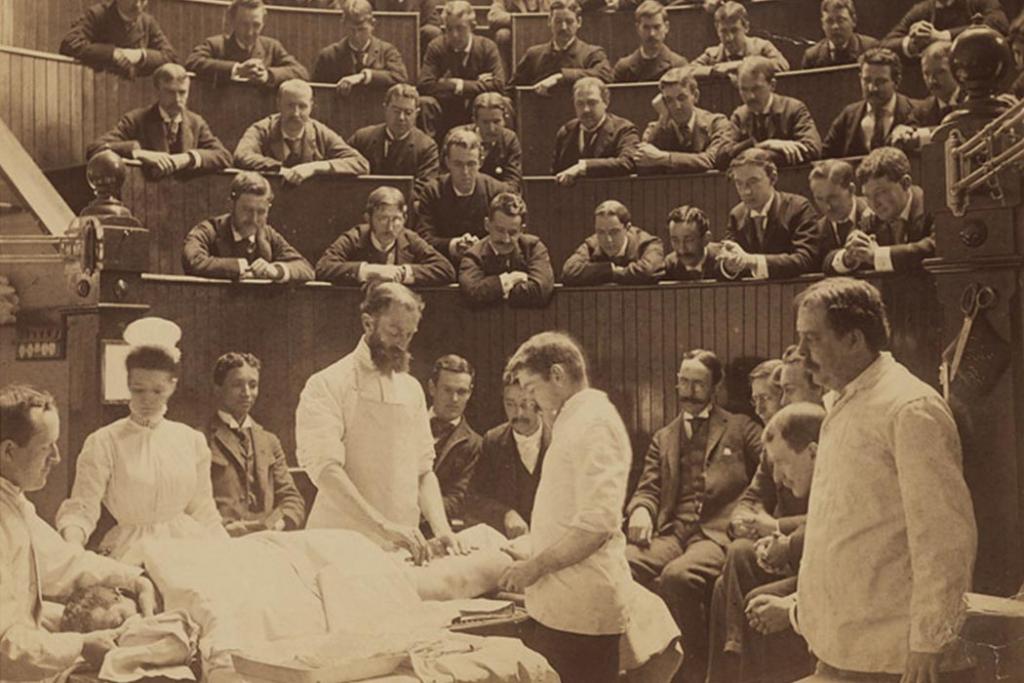

Even if I had been born into great wealth and privilege in 1859, it would still about 33 more years until two innovative physicians applied a newfangled technology known as x-rays to enlarged lymph nodes in Hodgkin’s patients and witnessed significant reduction in their size. And even then, it would be another half century before more advancements in radiation treatments for advance cases of Hodgkin’s were seen and decades still until those types of cases were cured.

My medical salvation, therefore, comes down to an accident of birth.

Had I not been born at the particular place and time in history that I was, if I had been more a century or so earlier, I would be dead by no fault of my own and there is absolutely nothing I could do about it no matter how many coffee enemas or kale smoothies I tried.

But what about my spiritual salvation?

What if I had still been born in 1983, but in Pyongyang, North Korea instead of Nashville, TN?

What if I had been born totally cut-off from the outside world in a land where Christianity is not only illegal, but for all intents and purposes non-existent, instead of right in the buckle of the Bible Belt?

And what if I died there, never having travelled outside my homeland, never hearing about Jesus, and never being told I had to repent of my sins and accept Jesus as my personal Lord and Savior?

It wouldn’t be my fault because I had no choice in where I was born or what opportunities my circumstances allowed.

So, would I go to hell?

If I would, it sure seems like a particularly cruel accident of birth.

Now, I’m sure this will come as a massive shock, but cancer has a way of changing your perspective on things, life and eternity in particular.

One thing that’s really struck me is how profound a role chance plays in our lives. (And before you yell at me in the comments section about how chance doesn’t existent and everything is pre-ordained by God, allow me to direct you to my previous post or this one to see what I think of that sort of theology.)

I’ve said all along that I consider myself incredibly lucky. Not lucky that I have cancer, but lucky that I have the curable form of cancer I do and even luckier to have an amazing support system around me. I fully, 100% believe God has had a hand in all of that, bringing good out of a terrible situation (terribleness which, again, I do not believe God caused).

But in my gratefulness, I wonder about those who aren’t so lucky, at least not according to the standards I grew up with in the Bible Belt.

According to the theology I grew up with, the only path to salvation and, therefore, the only way to get into heaven was to kneel at an altar (or pray where you stood), confess your sins, and accept Jesus as your personal Lord and Savior.

No profession, no heaven.

This, of course, always led to awkward conversations in Sunday School about all of the people in the Bible who came before Jesus. The Bible sure seemed to imply they were going to heaven and yet they never said the Sinner’s Prayer like we did. So, what gives?

Sure, the Sunday School teachers usually had handy supersessionist explanations ready to explain away that particular conundrum, but when it came to non-Jewish, post-Jesus folks who never heard of Jesus, things usually stayed in the awkward stage or just got more awkward if some smart-ass teenager like me brought up the issue of cultural isolation and the justice of God.

You know, like how I’m doing in this post right now by asking whether or not a just and loving God sends people to hell who live in such cultural isolation that the fully guaranteed evangelical Bible Belt path to heaven isn’t really an option simply by virtue of the accident of their birth.

Are those people really damned forever?

And if so, what does that say about God?

And if not, what does that say about our understanding of salvation?

Maybe it’s just the cancer talking, but it seems to me we place a great deal of weight on things like the accident of our birth that are both out of our control and more powerful than we can imagine.

It’s easy to divide up who goes where in eternity based on who’s professed what and who hasn’t and I think that’s part of the appeal of that particular brand of theology. But I’ve got to think a truly just and loving God isn’t quite so lazy or simplistic. Maybe, just maybe, God is more interested in how we live our lives than what we profess with our lips.

I get that idea from lots of places in scripture – like the entire ministry of Jesus, for example – but a few places in particular stick out. In the Old Testament, for example, there are weird places like in the book of Isaiah in which even Israel’s greatest enemies – Egypt and Assyria – seem to be welcomed into the family of God despite not going through the requisite rituals.

Then there’s Jesus himself saying, ““Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only the one who does the will of my Father in heaven.” And, of course, we shouldn’t forget the one moment in all of the gospels wherein Jesus describes exactly how he’ll separate the sheep and the goats and it’s not based on profession or theology but on how we treated the least of theses. Then there’s some of the last words Jesus ever told his disciples and, well, they may throw the biggest wrench in our obsession with conversion = heaven, “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.”

Notice what Jesus says there?

It’s “go and makes disciples,” not “go and make converts.”

It’s “go and make a better people,” not “go and see how many people you can get (or force) to agree with you.”

Better people make for a better world, converts just create more division and salvation is about the making of a better creation, not a more divided one.

Of course, that doesn’t negate our call to go and preach the good news, but it should call our attention to how much more concerned Jesus seems to be with how we live than what we believe.

So much so that even though we profess the “right” things, we may not enter the kingdom of heaven.

So much so that even though we profess Jesus as Lord, Lord it may not keep us from being goats if we didn’t care for the least of these.

So much so that even our enemies may end up among God’s people instead of us if we think we’ve already secured our place in heaven because we’re “chosen” and believe all the right things.

All that to say, as I sit here in a chair receiving my third dose of chemotherapy and thank God for the gift of an accidental birth that will allow me to go on living and see my kids grow up, I can’t help but wonder if maybe I should thank God for the love and grace I’ll never “need” because I was born in the “right” place and at the “right” time.

And while I’m at it, even if we never meet and never actually live next door to each other, maybe I should seek my neighbor’s forgiveness for damning them to hell because I didn’t realize just how incredible and expansive and surprising and working in ways and places I can’t even imagine the world changing, soul saving love and grace of God really is.