This is the final piece in a three-part series on Taxes, Rights, and Responsibilities. See the earlier posts here and here.

A year ago, on his March 11, 2010 program, broadcaster Glenn Beck challenged his audience to flee from any church using words like "social justice" or "economic justice," telling them it was a sign that they were in a church preaching a socialist and political gospel rather than a religious one.

When commentators or preachers talk about economic justice, some people still like to call that "class warfare."

And when politicians like President Barack Obama talk about government programs helping people in significant ways, it smacks of socialism for some, including the anonymous soul from Virginia who has paid for the mammoth billboard I pass on I-35 in Texas showing an angry-looking Obama and the words, "Socialist by Conduct."

I get that for some people, religion is personal, not political. This conflict is about more, though, than just a collision of religious understandings. It is also the big collision between the rights and responsibilities language most Americans believe in—the "freedom" ethic that Stanley Hauerwas pinpointed for us as the highest good of the modern West—and the rights and responsibilities language of the Founders, about doing what is right for the largest number of people.

It's also the collision between the freedom ethic and the Gospel imperative to help others, heal, feed, reconcile.

We are supposed to do justice. But the freedom ethic suggests that nobody should try to make us be just; we should be able to choose it for ourselves. Glenn Beck and his camp are clear on this: he's not against doing good, but he believes it should be purely a personal matter. As his executive producer Stu Burguiere put it back then, "Like most Americans, Glenn strongly supports and believes in 'social justice' when it is defined as 'good Christian charity.'"

Mr. Beck and others like him object to government programs, particularly when they're sold with the moral imperative of justice and require what Beck calls the redistribution of wealth, which is socialism, which is Marxism.

But I am asking, if for people of faith our highest goods are not economic fairness (that is, the unfettered freedom of my labor, my ideas, my dollars) but economic justice (that is, a concern for "us" instead of "me," care for the needy, and the commitment of resources to make that happen), doesn't this suggest we explore whether taxation and government programs may (if not should) be agents of this justice?

This is not my normal political bent; it is, actually, the theological position to which the last month of reading and thinking have led me. If you take away the Christian tradition's call, what's left behind is me, a squishy liberal with some progressive opinions and little will to see them carried out—and someone who, like everyone else, hears the freedom language and thinks: My taxes are too high, my taxes are too high.

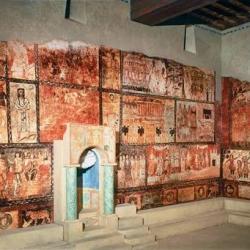

But for the past few weeks, we've been exploring the language of secular rights and responsibilities and examining the Christian tradition's normative understanding of our call to compassion and justice in the Bible and through the works of Augustine, Aquinas, and John Calvin, among others. Last week, we concluded with the idea that we as Christians have a responsibility to love and help others, and are called to serve others.

And so, after doing this work, it seems to me we can no longer ask whether or not we are supposed to seek justice for all; Calvin summed up the tradition in the Institutes when he gave us the daunting task of doing good to everyone who needs it without exception, because that is what Christians do (Institutes 3/7/6).

When we consider them from this viewpoint, our arguments about rights and responsibilities, our debates over taxing and spending, finally come down to this: Can secular government have a part in doing God's justice? Can taxes and spending help create a more just society?

Like Miss Molly Ivins, I suspect that taxes are the price we pay for our civilization, and should no more be regarded as the enemy than government should. At a talk in California in 2005, Miss Ivins said, in words she used throughout her life: