Dr. Gavin Ortlund is a Reformed Baptist author, speaker, pastor, scholar, and apologist for the Christian faith. He has a Ph.D. from Fuller Theological Seminary in historical theology, and an M.Div from Covenant Theological Seminary. Gavin is the author of seven books as well as numerous academic and popular articles. For a list of publications, see his CV. He runs the very popular YouTube channel Truth Unites, which seeks to provide an “irenic” voice on theology, apologetics, and the Christian life. See also his website, Truth Unites and his blog.

In my opinion, he is currently the best and most influential popular-level Protestant apologist, who (especially) interacts with and offers thoughtful critiques of Catholic positions, from a refreshing ecumenical (not anti-Catholic), but nevertheless solidly Protestant perspective. That’s what I want to interact with, so I have issued many replies to Gavin and will continue to do so. I use RSV for all Bible passages unless otherwise specified.

All of my replies to Gavin are collected on the top of my Calvinism & General Protestantism web page in the section, “Replies to Reformed Baptist Gavin Ortlund.” Gavin’s words will be in blue.

This is my 28th reply to his material.

*****

“Please Hit ‘Subscribe'”! If you have received benefit from this or any of my other 4,500+ articles, please follow this blog by signing up (w your email address) on the sidebar to the right, above where there is an icon bar, “Sign Me Up!”: to receive notice when I post a new blog article. This is the equivalent of subscribing to a YouTube channel. Please also consider following me on Twitter / X and purchasing one or more of my 55 books. All of this helps me get more exposure, and (however little!) more income for my full-time apologetics work. Thanks so much and happy reading!

*****

I am responding to a video from Gavin in debate with Orthodox priest, Fr. Stephen de Young on images and the early Church’s view of them. A one-minute and eleven seconds portion of it was tweeted on Protestant Collin Brook’s page on March 16th. As I write this (10:16 PM ET on 3-17-24), the excerpt has 110,000 views, 260 likes, and 59 retweets. Baptist apologist James White retweeted it also on 3-16-24. Collin commented, “This part of [the] recent dialogue was savagery.” It will no longer be (if it ever was: meaning that Gavin supposedly mightily prevailed) after I get through with it.

All the evidence that we have favors the view that any sort of cultic use of images was resoundingly rejected by Christians for the first 500 years of Church history . . . it’s everybody; it’s everywhere. It’s resounding, it’s clear, it’s bright. . . . If there’s anything we know about the early Church, we know that’s not what was happening. That is as clear as anything about the early Church. Can you name any advocate of icon veneration before 500 AD, . . . [who] says anything remotely positive about it?

[NOTE: if you want to actually see the context and full discussion on icon veneration, rather than simply this supposedly “gotcha!” soundbite, the entire video is called “Sola Scriptura or Holy Tradition? w/ Dr. Gavin Ortlund And Fr. Stephen De Young” (3-15-24 on The Transfigured Life channel. The portion on icons runs from 1:06:12-1:34:35. So it was over 28 minutes in length, from which Collin Brooks chose 71 seconds (about 4.2% of the whole), pronouncing it “savagery.”]

Once again we observe the spectacle of a Protestant apologist making a universal negative claim. Gavin isn’t claiming that the evidence is scanty or a small minority etc. He implies that no one believed it for 500 years. So, to refute his insinuation, all one has to do is come up with one example. But we have many more than that:

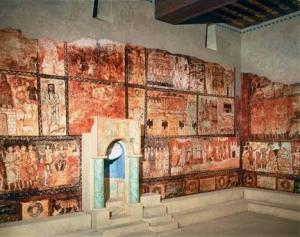

Catholic Encyclopedia (“Veneration of Images”): That Christians from the very beginning adorned their catacombs with paintings of Christ, of the saints, of scenes from the Bible and allegorical groups is too obvious and too well known for it to be necessary to insist upon the fact. The catacombs are the cradle of all Christian art. Since their discovery in the sixteenth century — on 31 May, 1578, an accident revealed part of the catacomb in the Via Salaria — and the investigation of their contents that has gone on steadily ever since, we are able to reconstruct an exact idea of the paintings that adorned them. That the first Christians had any sort of prejudice against images, pictures, or statues is a myth (defended amongst others by Erasmus) that has been abundantly dispelled by all students of Christian archaeology. The idea that they must have feared the danger of idolatry among their new converts is disproved in the simplest way by the pictures even statues, that remain from the first centuries. . . . The Christian sarcophagi were ornamented with indifferent or symbolic designs — palms, peacocks, vines, with the chi-rho monogram (long before Constantine), with bas-reliefs of Christ as the Good Shepherd, or seated between figures of saints, and sometimes, as in the famous one of Julius Bassus with elaborate scenes from the New Testament. And the catacombs were covered with paintings. . . .

Scenes from the New Testament are very common too, the Nativity and arrival of the Wise Men, our Lord’s baptism, the miracle of the loaves and fishes, the marriage feast at Cana, Lazarus, and Christ teaching the Apostles. There are also purely typical figures, the woman praying with uplifted hands representing the Church, harts drinking from a fountain that springs from a chi-rho monogram, and sheep. And there are especially pictures of Christ as the Good Shepherd, as lawgiver, as a child in His mother’s arms, of His head alone in a circle, of our Lady alone, of St. Peter and St. Paul — pictures that are not scenes of historic events, but, like the statues in our modern churches, just memorials of Christ and His saints. . . .

In the catacombs there is little that can be described as sculpture; there are few statues for a very simple reason. Statues are much more difficult to make, and cost much more than wall-paintings. But there was no principle against them. Eusebius describes very ancient statues at Caesarea Philippi representing Christ and the woman He healed there (Church History VII.18; Matthew 9:20-2). The earliest sarcophagi had bas-reliefs. As soon as the Church came out of the catacombs, became richer, had no fear of persecution, the same people who had painted their caves began to make statues of the same subjects. The famous statue of the Good Shepherd in the Lateran Museum was made as early as the beginning of the third century, the statues of Hippolytus and of St. Peter date from the end of the same century. The principle was quite simple. The first Christians were accustomed to see statues of emperors, of pagan gods and heroes, as well as pagan wall-paintings. So they made paintings of their religion, and, as soon as they could afford them, statues of their Lord and of their heroes, without the remotest fear or suspicion of idolatry.

The idea that the Church of the first centuries was in any way prejudiced against pictures and statues is the most impossible fiction. After Constantine (306-37) there was of course an enormous development of every kind. Instead of burrowing catacombs Christians began to build splendid basilicas. They adorned them with costly mosaics, carving, and statues. But there was no new principle. The mosaics represented more artistically and richly the motives that had been painted on the walls of the old caves, the larger statues continue the tradition begun by carved sarcophagi and little lead and glass ornaments. From that time to the Iconoclast Persecution holy images are in possession all over the Christian world. St. Ambrose (d. 397) describes in a letter how St. Paul appeared to him one night, and he recognized him by the likeness to his pictures (Ep. ii, in P.L., XVII, 821). St. Augustine (d. 430) refers several times to pictures of our Lord and the saints in churches (e.g. “De cons. Evang.”, x in P.L., XXXIV, 1049; Reply to Faustus XXII.73); he says that some people even adore them (“De mor. eccl. cath.”, xxxiv, P.L., XXXII, 1342). St. Jerome (d. 420) also writes of pictures of the Apostles as well-known ornaments of churches (In Ionam, iv). St. Paulinus of Nola (d. 431) paid for mosaics representing Biblical scenes and saints in the churches of his city, and then wrote a poem describing them (P.L., LXI, 884). Gregory of Tours (d. 594) says that a Frankish lady, who built a church of St. Stephen, showed the artists who painted its walls how they should represent the saints out of a book (Hist. Franc., II, 17, P.L., LXXI, 215). In the East St. Basil (d. 379), preaching about St. Barlaam, calls upon painters to do the saint more honour by making pictures of him than he himself can do by words (“Or. in S. Barlaam”, in P.G., XXXI). St. Nilus in the fifth century blames a friend for wishing to decorate a church with profane ornaments, and exhorts him to replace these by scenes from Scripture (Epist. IV, 56). St. Cyril of Alexandria (d. 444) was so great a defender of icons that his opponents accused him of idolatry (for all this see Schwarzlose, “Der Bilderstreit” i, 3-15). . . .

Although representations of the Crucifixion do not occur till later, the cross, as the symbol of Christianity, dates from the very beginning. Justin Martyr (d. 165) describes it in a way that already implies its use as a symbol (Dialogue with Trypho 91). He says that the cross is providentially represented in every kind of natural object: the sails of a ship, a plough, tools, even the human body (Apol. I, 55). According to Tertullian (d. about 240), Christians were known as “worshippers of the cross” (Apol., xv). Both simple crosses and the chi-rho monogram are common ornaments of catacombs; combined with palm branches, lambs and other symbols they form an obvious symbol of Christ. After Constantine the cross, made splendid with gold and gems, was set up triumphantly as the standard of the conquering Faith. A late catacomb painting represents a cross richly jewelled and adorned with flowers. Constantine’s Labarum at the battle of the Milvian Bridge (312), and the story of the finding of the True Cross by St. Helen, gave a fresh impulse to its worship. It appears (without a figure) above the image of Christ in the apsidal mosaic of St. Pudentiana at Rome, in His nimbus constantly, in some prominent place on an altar or throne (as the symbol of Christ), in nearly all mosaics above the apse or in the chief place of the first basilicas (St. Paul at Rome, ibid., 183, St. Vitalis at Ravenna). In Galla Placidia’s chapel at Ravenna Christ (as the Good Shepherd with His sheep) holds a great cross in His left hand. The cross had a special place as an object of worship. It was the chief outward sign of the Faith, was treated with more reverence than any picture “worship of the cross” (staurolatreia) was a special thing distinct from image-worship, so that we find the milder Iconoclasts in after years making an exception for the cross, still treating it with reverence, while they destroyed pictures. A common argument of the imageworshippers to their opponents was that since the latter too worshipped the cross they were inconsistent in refusing to worship other images (see ICONOCLASM). . . .

The veneration of images

Distinct from the admission of images is the question of the way they are treated. What signs of reverence, if any, did the first Christians give to the images in their catacombs and churches? For the first period we have no information. There are so few references to images at all in the earliest Christian literature that we should hardly have suspected their ubiquitous presence were they not actually there in the catacombs as the most convincing argument. But these catacomb paintings tell us nothing about how they were treated. We may take it for granted, on the one hand, that the first Christians understood quite well that paintings may not have any share in the adoration due to God alone. Their monotheism, their insistence on the fact that they serve only one almighty unseen God, their horror of the idolatry of their neighbours, the torture and death that their martyrs suffered rather than lay a grain of incense before the statue of the emperor’s numen are enough to convince us that they were not setting up rows of idols of their own. On the other hand, the place of honour they give to their symbols and pictures, the care with which they decorate them argue that they treated representations of their most sacred beliefs with at least decent reverence. It is from this reverence that the whole tradition of venerating holy images gradually and naturally developed. After the time of Constantine it is still mainly by conjecture that we are able to deduce the way these images were treated. The etiquette of the Byzantine court gradually evolved elaborate forms of respect, not only for the person of Ceesar but even for his statues and symbols. Philostorgius (who was an Iconoclast long before the eighth century) says that in the fourth century the Christian Roman citizens in the East offered gifts, incense, and even prayers, to the statues of the emperor (Hist. eccl., II, 17). It would be natural that people who bowed to, kissed, incensed the imperial eagles and images of Caesar (with no suspicion of anything like idolatry), who paid elaborate reverence to an empty throne as his symbol, should give the same signs to the cross, the images of Christ, and the altar. So in the first Byzantine centuries there grew up traditions of respect that gradually became fixed, as does all ceremonial.

Hippolytus: And they make counterfeit images of Christ, alleging that these were in existence at the time (during which our Lord was on earth, and that they were fashioned) by Pilate. (The Refutation of All Heresies, 7.20)

Basil the Great: Worshipping as we do God of God, we both confess the distinction of the Persons, and at the same time abide by the Monarchy. We do not fritter away the theology in a divided plurality, because one Form, so to say, united in the invariableness of the Godhead, is beheld in God the Father, and in God the Only begotten. For the Son is in the Father and the Father in the Son; since such as is the latter, such is the former, and such as is the former, such is the latter; and herein is the Unity. So that according to the distinction of Persons, both are one and one, and according to the community of Nature, one. How, then, if one and one, are there not two Gods? Because we speak of a king, and of the king’s image, and not of two kings. The majesty is not cloven in two, nor the glory divided. The sovereignty and authority over us is one, and so the doxology ascribed by us is not plural but one; because the honour paid to the image passes on to the prototype. Now what in the one case the image is by reason of imitation, that in the other case the Son is by nature; and as in works of art the likeness is dependent on the form, so in the case of the divine and uncompounded nature the union consists in the communion of the Godhead. (The Holy Spirit, ch. 18, sec. 45)

Methodius of Olympus (d. c. 311): The images of God’s angels, which are fashioned of gold, the principalities and powers, we make to His honour and glory. (From the Discourse on the Resurrection, Part 2)

John Chrysostom: And it became so frequent that this name [of St. Meletios] echoed around from every direction everywhere both in side streets and in the marketplace and in fields and on highways. But you didn’t experience so much just at the name, but even at the depiction of his body. At least, what you did with names, this you practiced, too, in the case of that man’s image. For truly, many carved that holy image on finger rings and on seals and on cups and on bedroom walls and all over the place so that one didn’t just hear that holy name, but also saw the depiction of his body all over the place and had a double consolation for his loss. (Homily in Praise of Saint Meletios)

Eusebius: For there stands upon an elevated stone, by the gates of her house, a brazen image of a woman kneeling, with her hands stretched out, as if she were praying. Opposite this is another upright image of a man, made of the same material, clothed decently in a double cloak, and extending his hand toward the woman. At his feet, beside the statue itself, is a certain strange plant, which climbs up to the hem of the brazen cloak, and is a remedy for all kinds of diseases. They say that this statue is an image of Jesus. It has remained to our day, so that we ourselves also saw it when we were staying in the city. Nor is it strange that those of the Gentiles who, of old, were benefited by our Savior, should have done such things, since we have learned also that the likenesses of his apostles Paul and Peter, and of Christ himself, are preserved in paintings, the ancients being accustomed, as it is likely, according to a habit of the Gentiles, to pay this kind of honor indiscriminately to those regarded by them as deliverers. (Church History, 7.18)

Theodoret: It is said that the man [St. Symeon] became so celebrated in the great city of Rome that at the entrance of all the workshops men have set up small representations of him, to provide thereby some protection and safety for themselves. (Life of St. Symeon the Stylite, 11)

Philip Schaff’s Summary: [T]he prejudices of the ante-Nicene period against images in painting or sculpture continued alive, through fear of approach to pagan idolatry, or of lowering Christianity into the province of sense. But generally the hostility was directed only against images of Christ; and from it, as Neander justly observes, we are by no means to infer the rejection of all representations of religious subjects; for images of Christ encounter objections peculiar to themselves. . . .

The prevalent spirit of the age already very decidedly favored this material representation as a powerful help to virtue and devotion, especially for the uneducated classes, whence the use of images, in fact, mainly proceeded. (History of the Christian Church, Vol. III: Nicene and Post-Nicene Christianity, New York: Scribner’s, 5th edition, 1910, reprinted by Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1974, 565, 566-567)

**

Now, I’d like to make a comparison between Catholic and Protestant patristic support. The whole point of Gavin’s claim in the video above is to make out that (paraphrasing) “here is this belief held by both Catholics and Orthodox that has absolutely no support from Church fathers in the first 500 years of the Church. How can that be?!” He assumes that this is a strong argument against us. In other words, we can say that there ought to be support in the fathers for any given theological belief that a Christian holds.

We agree with the previous sentence. I think I showed above that evidence for widespread use and veneration of images in the patristic era is not totally lacking. It’s surely and obviously less than that for many other doctrines, but it’s not nonexistent (and that was his claim, which is now decisively refuted), and there is also a line of argument — that is present but not developed in my defense — for why it is less prevalent.

Let’s assume for a moment — for the sake of argument — that it was totally absent, as Gavin claimed (“Can you name any advocate of icon veneration before 500 AD, . . . [who] says anything remotely positive about it?”). Even if that were actually true, the degree of patristic support for the Protestant is much, much less than it is for Catholicism. Veneration of images; even bowing before them, is also an explicit teaching of Holy Scripture, as I have massively demonstrated. See the section, “Veneration of Icons and Images (Including of God) / Statues / Holy Objects / Holy Days” on my Saints, Purgatory, & Penance web page.

But if we look at, for example, one of the two “pillars” of the “Protestant Reformation”: sola fide (faith alone), we find three well-known Protestant apologists and historians making summary statements about its utter lack of support among the Church fathers, and even up until the 16th century when Luther’s successor Philip Melanchthon pulled it out of a hat. First, I cite the late Protestant apologist Norman Geisler (who influenced my own apologetics outlook in many ways):

For Augustine, justification included both the beginnings of one’s righteousness before God and its subsequent perfection — the event and the process. What later became the Reformation concept of ‘sanctification’ then is effectively subsumed under the aegis of justification. Although he believed that God initiated the salvation process, it is incorrect to say that Augustine held to the concept of ‘forensic’ justification. This understanding of justification is a later development of the Reformation . . .

Before Luther, the standard Augustinian position on justification stressed intrinsic justification. Intrinsic justification argues that the believer is made righteous by God’s grace, as compared to extrinsic justification, by which a sinner is forensically declared righteous (at best, a subterranean strain in pre-Reformation Christendom). With Luther the situation changed dramatically . . .

. . . one can be saved without believing that imputed righteousness (or forensic justification) is an essential part of the true gospel. Otherwise, few people were saved between the time of the apostle Paul and the Reformation, since scarcely anyone taught imputed righteousness (or forensic justification) during that period! . . . . . (Roman Catholics and Evangelicals: Agreements and Differences, with Ralph E. MacKenzie, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1995, 502, 85, 222; my italics and bolding)

The renowned Protestant scholar Alister McGrath makes virtually the same point:

Whereas Augustine taught that the sinner is made righteous in justification, Melanchthon taught that he is counted as righteous or pronounced to be righteous. For Augustine, ‘justifying righteousness’ is imparted; for Melanchthon, it is imputed in the sense of being declared or pronounced to be righteous. Melanchthon drew a sharp distinction between the event of being declared righteous and the process of being made righteous, designating the former ‘justification’ and the latter ‘sanctification’ or ‘regeneration.’ For Augustine, these were simply different aspects of the same thing . . .

The importance of this development lies in the fact that it marks a complete break with the teaching of the church up to that point. From the time of Augustine onwards, justification had always been understood to refer to both the event of being declared righteous and the process of being made righteous. . . .

The Council of Trent . . . reaffirmed the views of Augustine on the nature of justification . . . the concept of forensic justification actually represents a development in Luther’s thought . . . .

Trent maintained the medieval tradition, stretching back to Augustine, which saw justification as comprising both an event and a process . . . (Reformation Thought: An Introduction, 2nd edition, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1993, 108-109, 115; my italics and bolding)

And the great Protestant Church historian Philip Schaff concurred:

If any one expects to find in this period [100-325], or in any of the church fathers, Augustin himself not excepted, the Protestant doctrine of justification by faith alone, . . . he will be greatly disappointed . . . Paul’s doctrine of justification, except perhaps in Clement of Rome, who joins it with the doctrine of James, is left very much out of view, and awaits the age of the Reformation to be more thoroughly established and understood. (Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Vol. 2, 588-589)

So two of the three are essentially saying that there is no support whatsoever for “faith alone” in the entire patristic period and indeed all the way up to even past Luther, to Melanchthon, when the novel innovation took place (Schaff’s statement addresses the period up to 325 AD). And this is — all agree — a central teaching, having to do with soteriology (the theology of salvation); how one is saved. If the alleged (but not actual) lack of patristic support for veneration of images is supposedly such a “victory” for Protestantism, why is not the actual lack of any patristic support for sola fide a strike against the Protestant worldview?

Goose and gander . . . I’ve done a lot less work on the soteriology of the Church fathers than I have about their rule of faith, but I plan on doing much more. For now, see what I have in the “Salvation / Justification / “Faith Alone” / Soteriology” section of my Fathers of the Church web page. Even so, I still have seventeen articles in that section, with many more to come. Stay tuned!

Moreover, I contend that interrelated notions of “faith alone” / extrinsic, imputed justification / the formal separation of justification and sanctification / denial of meritorious works are massively contradicted in the Bible as well, and aspects that are supported are those in which Catholics wholeheartedly agree with Protestants (initial monergistic justification, a denial of works-salvation or Pelagianism, sola gratia, etc.). See my debate with Brazilian Calvinist Francisco Tourinho on the topic, which is to be made into a book in Portugese, and is available for free on my blog: Justification: A Catholic Perspective (2023). See also scores of articles in the first (top) section of my Salvation, Justification, & “Faith Alone” web page.

The other self-described “pillar” of the Protestant Revolt is sola Scriptura. Protestants try very hard, but they have not, in my opinion (and I have studied this for many thousands of hours) established that any Church father actually held this viewpoint. I myself have documented how some 40 or so major Church fathers (yes, including the Protestant “hero” St. Augustine) in fact held views that expressly contradict sola Scriptura (see the “Bible / Tradition / Sola Scriptura / Perspicuity / Rule of Faith” section of my Fathers of the Church web page).

And if anyone wants to see how strong the alleged support for this novel doctrine is in Holy Scripture, well, I wrote an entire book demonstrating that there is none, entitled, 100 Biblical Arguments Against Sola Scriptura (2012). I also took on two men who are considered the best historical defenders of the false doctrine, in my book, Pillars of Sola Scriptura: Replies to Whitaker, Goode, & Biblical “Proofs” for “Bible Alone” (2012), and I’ve written more about this topic than anything else, among my 4,500+ articles. See sections III-V on my Bible, Tradition, Canon, & “Sola Scriptura” web page).

Thus, I strongly contend (and I can back it up) that both Protestant “pillars” have neither patristic nor biblical support. Perhaps this is why a very good Protestant apologist like Gavin Ortlund spends time making the now-falsified claim that there is no patristic evidence whatsoever for veneration of images, rather than trying to argue against the true and profound lack of same for the two “pillars” of the Protestant Reformation.

It’s a failed attempt, in other words, to “turn the tables” regarding the issue of patristic support (both sides claiming to have far more than the other). The famous statement of St. John Henry Cardinal Newman (that drives Protestants crazy) remains as true as ever: “to be deep in history is to cease to be a Protestant.” I will do my best to, in effect, defend it by taking on specific instances of Protestants trying hard (E for effort and zeal!) but failing to show that his maxim is untrue.

**

Related Reading

Responding to Gavin Ortlund on Icon Veneration (Suan Sonna, 2023) [excellent, thorough 142-page rebuttal]

See Gavin’s brief response on my Facebook page.

*

***

*

Practical Matters: Perhaps some of my 4,500+ free online articles (the most comprehensive “one-stop” Catholic apologetics site) or fifty-five books have helped you (by God’s grace) to decide to become Catholic or to return to the Church, or better understand some doctrines and why we believe them.

Or you may believe my work is worthy to support for the purpose of apologetics and evangelism in general. If so, please seriously consider a much-needed financial contribution. I’m always in need of more funds: especially monthly support. “The laborer is worthy of his wages” (1 Tim 5:18, NKJV). 1 December 2021 was my 20th anniversary as a full-time Catholic apologist, and February 2022 marked the 25th anniversary of my blog.

PayPal donations are the easiest: just send to my email address: [email protected]. Here’s also a second page to get to PayPal. You’ll see the term “Catholic Used Book Service”, which is my old side-business. To learn about the different methods of contributing (including Zelle), see my page: About Catholic Apologist Dave Armstrong / Donation Information. Thanks a million from the bottom of my heart!

*

***

Photo credit: sacred images on the walls of the 3rd-century Dura-Europos church in Syria [Summa Apologia]

Summary: Gavin Ortlund challenged: “Can you name any advocate of icon veneration before 500 AD?” I provide several examples from Church fathers and the catacombs.