- Trending:

- Pope Leo Xiv

- |

- Israel

- |

- Trump

- |

- Social Justice

- |

- Peace

- |

- Love

RELIGION LIBRARY

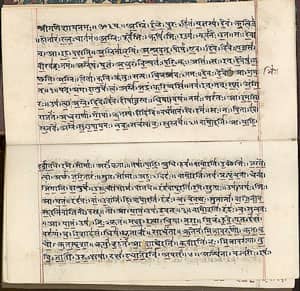

Hinduism

Sacred Texts

The textual tradition of Hinduism encompasses an almost incomprehensible collection of oral and written scriptures that include myths, rituals, philosophical speculation, devotional poems and songs, local histories, and so on. There are two basic categories of religious texts within this vast collection, Shruti (revealed) and Smrti (remembered). Shruti generally refers to the Vedas, the Brahmanas, and the Upanishads; some Hindus also classify the Bhagavad Gita as shruti. Smrti typically refers to everything else.

The textual tradition of Hinduism encompasses an almost incomprehensible collection of oral and written scriptures that include myths, rituals, philosophical speculation, devotional poems and songs, local histories, and so on. There are two basic categories of religious texts within this vast collection, Shruti (revealed) and Smrti (remembered). Shruti generally refers to the Vedas, the Brahmanas, and the Upanishads; some Hindus also classify the Bhagavad Gita as shruti. Smrti typically refers to everything else.

| Shruti (revealed) | Smrti (remembered) |

| *the Vedas | *vast collection of myths, epic texts, and traditions |

| *the Brahmanas | |

| *the Upanishads (=Vedanta) | |

| [*the Bhagavadgita] |

The Vedas form the foundation of Hinduism, the bedrock upon which the entire tradition is built. Indeed, although Hindus of different schools and different sects typically align themselves with different texts, virtually all Hindus recognize the legitimizing authority of the Vedas. There are four primary Vedas—the Rig Veda, Yajur Veda, Sama Veda, and Atharva Veda—that together comprise over 1,000 hymns of praise addressed to the gods, as well elaborate instructions on how to conduct sacrifices to these divine beings, and a huge corpus of myths. Each Veda, in turn, has four divisions. The primary division is called the Samhita, which is the vedic text itself. The other three divisions—the Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and Upanishads—are commentaries and elaborations on the primary vedic text.

| VEDIC TEXTS |

|

Although technically included in the Vedas, the Upanishads are in fact rather un-vedic scriptures. The principal Upanishads, of which there are traditionally thirteen, were probably composed between 800 and 100 B.C.E. The Upanishads are typically understood by the Hindu tradition as an extension of the Vedas; they are also known, collectively, as Vedanta, the "completion" of the Vedas. However, the Upanishads significantly reject many of the Vedic ideas and practices. The Upanishads largely reject the multiple deities of the Vedas, arguing that all one gets from such ritual is more material. The sages who composed the Upanishads sought something more—ultimate, eternal salvation. Thus they posit a single, eternal, impersonal divine force that animates and permeates the entire cosmos—Brahman.

| List of "principal" Upanishads (there are over 100 others) |

|

|

|

The word "Upanishad"derives from a Sanskrit term that means "to sit near." Specifically, it refers to a student sitting near a teacher and learning directly through questions and answers. The bulk of the Upanishads record such discourses, and the single most pressing question posed by the students to the teachers is: "What is the nature of Brahman?" This is a deceptively simple question. On a basic level, the answer is equally simple: "Everything is Brahman." But behind this simple answer is tremendous theological complexity.

The Upanishads hold that since everything is Brahman, the individual is also Brahman. What separates the individual from the absolute Brahman, and thus from salvation, or moksha (release), is ignorance of this fundamental reality. Individuals think that the things that make them who they are, such as one's relationships, or appearance, or even thoughts, are real. The Upanishad holds that these are merely elaborate illusions. We hold on to these illusions, and it is this holding that keeps us from realizing the ultimate truth, Brahman. Thus the Upanishads advocate an ascetic path. If one wishes to realize the ultimate, then one must detach oneself from all of these unreal things. One must go off and meditate on the reality of Brahman, which begins with meditation on the self, the atman, which is in essence the same as Brahman.

The category of scripture known as smrti is vast, encompassing the classic epic texts—the Mahabharata and the Ramayana—as well as a group of texts known as Puranas, and all manner of local myths and legends. The Mahabharata, the "Great story of India," is a huge text of over 75,000 verses, or nearly two million words, composed over a long period, probably between the 5th century B.C.E. and the 4th century C.E. It is a difficult text to classify, since it contains mythology, philosophy, theology, historical events (it is often classified in Hinduism as "ithihasa," or history), ritual, and social commentary. Early on, the text states: "What is found here, may be found elsewhere. What is not found here, will not be found elsewhere."

The category of scripture known as smrti is vast, encompassing the classic epic texts—the Mahabharata and the Ramayana—as well as a group of texts known as Puranas, and all manner of local myths and legends. The Mahabharata, the "Great story of India," is a huge text of over 75,000 verses, or nearly two million words, composed over a long period, probably between the 5th century B.C.E. and the 4th century C.E. It is a difficult text to classify, since it contains mythology, philosophy, theology, historical events (it is often classified in Hinduism as "ithihasa," or history), ritual, and social commentary. Early on, the text states: "What is found here, may be found elsewhere. What is not found here, will not be found elsewhere."

The central story of the Mahabharata is the dynastic conflict between two sets of paternal cousins, the Pandavas and the Kauravas, each of whom claim the rightful rule of Bharata (India). Their conflict culminates in an epic battle that is eventually won by the Pandavas. Over the course of the narrative, issues of kinship and kingship, familial loyalty and duty, and ultimately good and evil are complexly debated.

The most well-known part of the Mahabharata is the Bhagavad Gita, the "Song of the Blessed One," which becomes one of the most important theological treatises in all of Hinduism. The central message of the Bhagavad Gita is a complex reconciliation of the seemingly contradictory worldview of the Vedas—emphasizing ritual action and duty—and the Upanishads—emphasizing renunciation of worldly involvement and meditation. The text consists of a conversation between one of the Pandavas, Arjuna, and the god Krishna. Krishna resolves the conflict by proposing a new path: that of selfless devotion (bhakti) to the divine (here Krishna). As long as one is selflessly devoted, it does not ultimately matter what sorts of actions one engages in, since they are all, ultimately, part of the divine.

The most well-known part of the Mahabharata is the Bhagavad Gita, the "Song of the Blessed One," which becomes one of the most important theological treatises in all of Hinduism. The central message of the Bhagavad Gita is a complex reconciliation of the seemingly contradictory worldview of the Vedas—emphasizing ritual action and duty—and the Upanishads—emphasizing renunciation of worldly involvement and meditation. The text consists of a conversation between one of the Pandavas, Arjuna, and the god Krishna. Krishna resolves the conflict by proposing a new path: that of selfless devotion (bhakti) to the divine (here Krishna). As long as one is selflessly devoted, it does not ultimately matter what sorts of actions one engages in, since they are all, ultimately, part of the divine.

The Ramayana, like the Mahabharata, is a huge text. At its core is the story of the god Rama and his wife Sita, their exile, Sita's abduction by an evil demon (Ravana), Rama's rescue of Sita, and the eventual restoration of their kingdom. Interwoven into the narrative is a mixture of myths and history and theology as well as a particular focus on the proper actions of a dharmic (moral, righteous) ruler.

The Ramayana, like the Mahabharata, is a huge text. At its core is the story of the god Rama and his wife Sita, their exile, Sita's abduction by an evil demon (Ravana), Rama's rescue of Sita, and the eventual restoration of their kingdom. Interwoven into the narrative is a mixture of myths and history and theology as well as a particular focus on the proper actions of a dharmic (moral, righteous) ruler.

The Puranas (the word means "Ancient") are a diverse collection of texts that, like the epics, contain mythology, theology, history, and geography. Many of the Puranas focus on a single god or even a single temple, narrating key myths and philosophical/theological principles.

The categories of Shruti and Smrti are essential for understanding the vast array of Hindu scriptures, but it is important to note that not all Hindu scriptures easily fit into these categories. There are also thousands of "lesser," local scriptures—many of them only known in oral form and known only in vernacular languages—that are central to the lives of many, many Hindus.

Study Questions:

1. How are Hindu texts categorized? What are some examples of each, and why has more authority?

2. What is the purpose of the Vedas, and how are they divided?

3. Why might it be problematic to name the Upanishads as Vedic texts? What is their main teaching?

4. Describe the role of the Bhagavad Gita within Hindu scripture.