Patheos – the overarching home of Patheos Pagan – does book clubs and anyone from any channel is able to join it. Most of the books don’t interest me, but this month I decided to try one of the books. Broken Gods: Hope, Healing, and the 7 Longings of the Human Heart, is by Gregory K. Popcak, PhD., a Catholic, therapist, and fellow blogger at Patheos (Faith on the Couch).

I’ll admit the title intrigued me. I wondered what a Christian could be intimating by “Gods.” The blurb suggested Popcak would be discussing the idea of divinization. One of the things I studied extensively in graduate school was theological anthropology (who are we? what is the nature of the human person? what is our purpose? etc) and the early Church Fathers. The concept of divinization is central to both of those studies. It’s been years since I looked at this topic. What would I see in this topic now?

I’ll admit the title intrigued me. I wondered what a Christian could be intimating by “Gods.” The blurb suggested Popcak would be discussing the idea of divinization. One of the things I studied extensively in graduate school was theological anthropology (who are we? what is the nature of the human person? what is our purpose? etc) and the early Church Fathers. The concept of divinization is central to both of those studies. It’s been years since I looked at this topic. What would I see in this topic now?

Let’s get the obvious out of the way first: I am not the target audience of this book. This book is for Christians, specifically middle class, mainstream entrenched Christians. I am not that.

Much of the book repeats the general frame and tone that the Christian self-help books I read in the ’90’s had. I guess not much has changed. There are sweeping generalizations about what people want and what is best and healthy for persons; none of it sitting well with me. There is the mingling of neuroscience language and psychological words to attempt a bit of academic gravitas. There is the speaking about others’ experience. (“But atheists like Carter are lost in pessimism without even knowing it.” p.9) The book is divided up into seven chapters, following the seven deadly sins and what needs they mask. Each chapter ends with prayers and reflection points. Again, I feel like if you’ve read one Christian self-help book, you’ve read them all.

Reading the chapter on justice left a bad taste in my mouth, especially in the wake of high profile racial tension in the United States. Popcak describes the “divine longing for justice” as the “foundation for our natural expectation that everything should work infinitely better than it does” (p. 87). Injustice is discussed in terms of “big and small offenses” and “frustrated expectations.” There is no mention of actual, systemic injustice in this world. And all of injustice is diminished with the theology of the Fall – you know, everything’s just worse since then. Again, this kind of writing smacks of mollycoddling middle class Christians, rather than making them uncomfortable talking about actual injustice and suffering.

This middle class connection is made all the stronger when Popcak talks about work in the chapter on trust. God was a good “boss” in the Garden of Eden; our work was “dignified, profitable” (p. 120). Later on that same page he talks about how work ideally makes us feel accomplished and helps us “to become everything we are created to be.” Going on, he says: “Toil is, essentially, work stripped of our trust that the things we are asked to do are not beneath us…” So, in the garden no one had to scoop poop? Hard work is toil? There’s a lot to unpack here, conflating hard work with toil with indignity. But just in case you were nervous, because you might have a full savings account, we are reminded that saving money and being “financially blessed” isn’t bad. Do Christians still need this pointed out? Apparently so.

And since I’m a Pagan let me not fail to point out that Popcak confuses New Age and Neo-Paganism, and insults us by saying that “the modern neo-pagan [sic] fails to worship anyone…. besides himself.” p.11. So much for academic gravitas.

But not everything is awful. In his chapter on peace, Popcak makes a great point when he talks about the apathy of sloth. Peace isn’t the absence of conflict. “It is one thing if through thoughtful prater, careful discernment, and responsible consultation we consciously decide that it would be better to leave something alone. It is another thing to simply fail to consider the question in the first place out of a desire to avoid trouble.” (p. 110)

What is most interesting and unique about this book is Popcak’s focus on divinization. It is a little acknowledged aspect of Christian theology, but one that I find incredibly important and liberating. The Eastern Orthodox tradition has developed this concept most fully and, in my experience, brings it out more than the Western Christian tradition. Popcak, as a Roman Catholic, is perfectly situated to bring this concept to greater modern attention. He uses quotes from Papal writings, various saintly mystics, and ancient liturgies. The entire book is squarely situated in the broader Christian tradition – and I appreciate that.

Divinization, theosis, is the process of becoming a god. This is one of the goals and promises of Christianity. Yes! Christians ideally not just become like their god, but become gods. Now, it’s important to note the distinction between big G God and little g god in Christianity. For me, there is little distinction. The Christian mystics and Church Fathers all acknowledge that the goal of Christianity is perfection – not perfection in the sense that I will do every perfectly, that I will attain some Platonic ideal of being human. Rather, perfection is union so complete with their God that they become gods themselves. I think this is an incredibly beautiful theological idea and this idea is present (more or less) in the traditions I practice now.

I do believe that we are gods. Each and every one of us. I believe in the immanence of animating spirit, that every thing has the spark of the divine within it. This is one of the tenets of Christianity I took deeply to heart and have found reflected in nearly every mystic tradition I have studied. Taking seriously this theological claim, as well as my own lived experience, has led me more deeply into a panentheistic polytheistic animism. What this understanding of divinization and the inherent divinity of all things leads to next is profound relationship.

My favorite chapter in Broken Gods, hands down, was the chapter on communion. Intimate interdependence is the bedrock of human relationship and Popcak not only grasps that, but also understands the necessity of boundaries (chastity in his terms) in creating and safeguarding healthy relationships. I was particularly impressed with this bit:

” ‘All my relationships aren’t sexual.’ Of course they are. While not every relationship is genital in the sense that every relationship involves sexual intercourse, every relationship is sexual – in the broadest sense of the word – because every relationship involves both the sharing of oneself with another and generativity, that is, the creation of something that is bigger than oneself and potentially outlives the self.” (p. 171)

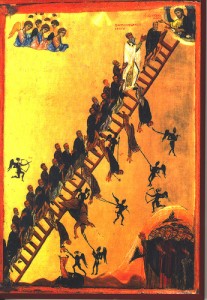

At the end of the book he mentions St John of the Cross’s “ladder of divine love.” I relate so strongly to this bit of mystic wisdom. The first stage of the way is purgative. We remove all that binds us and hinders us on our ascent. Next is the illumination and a “total reorientation of our desire,” where “we no longer experience our desires as a distraction.” I am so fully and completely on this part of the ladder. For so many years I thought my desires were out of place, making me unable to function in the world and society. Outwardly I was functioning fine, more or less, but the internal cost was incredibly high. Now, I see that my desires were not out of place or “weird;” I am merely myself and embracing my longings has actually set my life in order.

Popcak goes on: “Up to now, we’ve been afraid we would lose ourselves if we got too close to the fire. Now we’re finding that the more we are consumed by the fire, the more ‘ourselves,’ the more authentic we become.” (p. 179) I embrace the fire. I have prayed for the refining fire since I was 12 years old. It is the heart of the mystic yearning.

For Christians with no background in the Church Fathers or Christian mystics, this book might be a good way to introduce their ideas. Non-Christians have no need of this book at all, but instead I encourage everyone to go to the source. Read the Cappadocian Fathers (Saints Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian, and Gregory of Nyssa), St. John of the Cross, and the work of Vladimir Lossky.

As we approach the longest day of the year (in the Northern Hemisphere), may you embrace the fire! Jump in!