The word “eternity” scares us post-Christians. It was no contradiction for atheists like Nietzsche to disavow the existence of God while simultaneously reveling in the idea of eternity, but now that popular atheism has been irretrievably wed to the idea that truth is only in the material world, and that physical science rightfully usurps all other forms of knowledge, a rejection of God has come to mean a simultaneous rejection of eternity. Why? Because if truth is only known through science, and science deals with the physical world in its nebulas, atoms, and electromagnetic fields, then the one truth we must be absolutely sure of is that nothing is eternal, for the physical world is moving from a state of order to a state of final chaos. Entropy dictates a crumbling of the cosmic cookie. All things are exhaustible.

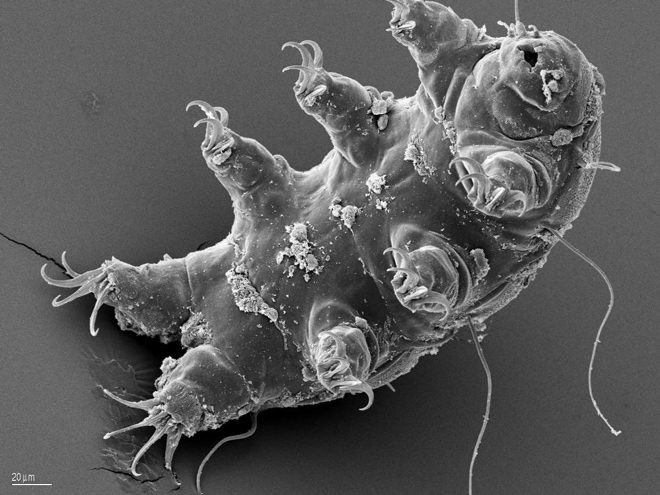

Now I’m not here to prove the existence of eternity. But if one were to stand up for its presence in human life, I imagine the first thing worth requesting of its critics would be to use an appropriate lens. If I deny the existence of bacteria by refusing to use a microscope, I hardly qualify as a serious scientist.

A similar issue plagues the denial of eternity. We ask that eternity — the inexhaustible and everlasting — be shown, as the nebula is shown, that is, as an object available to objective verification, but eternity is not a thing, it is only revealed by things. Or rather, knowing that eternity cannot be shown in a way subject to empirical science, we assume a priori that it is an illusion, and subsequently conduct scientific research to show the physicality of all human experiences that claim contact with the eternal. The God Helmet experiments come to mind, but these are notoriously dumb. Far more credible are the experiments regarding the nature of human love.

Contra the poets, contra the philosophers, and contra the theologians, in an objective, outside, scientific view of love, the thing is hardly eternal. Parents divorce, friendships fail, families scream, and even were two homo sapiens to claim eternal love and never cease loving for a second of their lives, still death would put an end to it all. From the view of a Martian regarding the phenomenon of love as a disinterested third party, we can safely say that love has nothing to do with eternity. This “ideal view” been taken by the scientists. “It’s all about the dopamine,” we’ve heard and heard again, or the serotonin, or the oxytocin. We can, as disinterested third parties, observe these chemicals in the brain, and these are finite, fading chemicals.

Or if that’s not your area of expertise, love is all about your major histocompatibility complex. Or it’s all about a tit-for-tat system, in which we love others so they don’t kill us. Whatever the case — or combination of cases — love is just another reality of the physical universe, subject, like all things, to entropy and eventual destruction. Love is not eternal.

Now all these claims are answerable in themselves. For instance, the claim that “love is chemical” assumes — in faith — that it has properly discerned the order of cause and effect, that “chemicals cause love,” and not that “love causes chemicals,” and certainly not that “since human beings are an eternal synthesis of body and soul, it would be silly to expects the spiritual reality of love to be apart from the physical reality of brain chemistry.”

But I would like to get to the heart of the issue, the fundamental problem I have with “knowing love scientifically.” It occurs to me that love as experienced by an objective, disinterested party is not “more truthfully known,” but less. Love apart from interested parties does not exist. It’d be foolish to say that the real truth about playing the guitar is known by the objective observer, who looks rationally upon the phenomenon and considers it variables, its mathematics, and physiological, biochemical realities. The truth about playing the guitar is known by the guitar player. Objects may be known in the objective perceiving, but actions — like “playing the guitar” or “loving the girl” — are known in the acting. Love is known in the loving. If it is known outside of loving, it is not known as love, but love-as-experienced-by-a-disinterested-party, which is, of course, no love at all. If you want to know love, love. Nothing more can be said.

But I would like to get to the heart of the issue, the fundamental problem I have with “knowing love scientifically.” It occurs to me that love as experienced by an objective, disinterested party is not “more truthfully known,” but less. Love apart from interested parties does not exist. It’d be foolish to say that the real truth about playing the guitar is known by the objective observer, who looks rationally upon the phenomenon and considers it variables, its mathematics, and physiological, biochemical realities. The truth about playing the guitar is known by the guitar player. Objects may be known in the objective perceiving, but actions — like “playing the guitar” or “loving the girl” — are known in the acting. Love is known in the loving. If it is known outside of loving, it is not known as love, but love-as-experienced-by-a-disinterested-party, which is, of course, no love at all. If you want to know love, love. Nothing more can be said.

In the first-person experience of love, it is far less obvious that love is not eternal. In love, lovers promise to love “forever.” In love, love precedes knowledge of the beloved, prompting us to say, “I’ve been waiting for you my whole life,” and “I loved you before I met you.” That love may fail is evidence to the Martian that the promises are based on the false premise of love’s eternity. To those in love, however, a failure to love is not evidence of love’s finite nature, but an evidence of human failure, which actually — and painfully — reaffirms the eternity of love.

Think about it. If love was finite, there could be no talk of “failure.” If love has nothing to do with the eternal, then there would be no guilt over the destruction of relationships, no pain over divorce, no heartache over estrangement from families and, more than all these things, no sense of injustice over the failure of love. Finite things are, after all, used up, and it’d make no more sense to weep over coming to a finish-line in love than it would to weep over finishing a meal. But love is experienced as eternal, giving rise to the expectation of eternity. When love is rudely cut short, the complaint is not over the finite nature of love, but over the lack of love in the other, the lack of the action of love, the inability of the lover to meet the eternal demand of love. Love is not proved finite, man is proved weak.

Imagine, for instance, an eternal tree in the middle of a lake.

The tree is beautiful, unaffected by the passage of time. It was, is, and always will be big and branching, immense and inviting. Delighting in its eternity, men and women climb its branches and eat its fruit. Now, if a man refused to be in the tree and to eat its fruit, his absence of action would be no evidence against the eternal nature of the tree. It would only be evidence of his inaction. So too with love. Our failures to remain in love are no testimony against its eternity. In fact, our bitterness and agony over failure is evidence of love’s true nature, evidence that it is eternal and thereby demands an eternal response, making all finite, limited, ending acts of love painful, confusing, and ultimately sinful.

Love — known in the loving — transcends time. We love the age gone by. A mother loves the baby she has yet to bear — not the abstract idea of a baby, mind you, but her particular, future baby, shrouded in the mystery of who, precisely, he will be, but nevertheless loved as himself and no other. A widow does not love the mere memory of her husband — such an accusation would be an offense. The widow loves her husband, and this love transcends time. These things cannot be true from a Martian perspective — for how could some one love what does not yet exist or exists no longer? — but this is not because the widow and the mother are fooled or lying. It is because the Martian perspective is not the perspective of love-as-present-action, but one of love-as-observed-object, and love is only known in the acting. It can only appear strange to the scientific view. For instance, it appears that love transcends the biological laws of nature, which dictate all things be “useful” in the Darwinian sense. We can love against the selfish persuasion of our genes, loving — to Nietzsche’s horror — the poor, the sick, the lame, the evil one, and even the enemy, loving to the point of our own death, fully convicted of the fact that we have found in love something far more dear than life. Love even transcends the boundaries of our human race: We can love our dogs and our countries.

So love appears to the lover as eternal, an ecstasy from the physical world, a transcendence from the bonds of matter and time. This mysticism is only ridiculous if we take on the view of one outside, peering in on love, but by doing so we cease to look at love, which is known in the loving, not the looking.

So when the atheist laughs at me for believing in “an invisible man in the sky,” I can’t help but laugh with him, for treating God as an observable object and arriving at disbelief is as ridiculous as my treating microbes as macrobes, refusing to use a microscope, and arriving at a disbelief in microbial life. What’s needed is the right perspective. God is not known in the observing. God is love, and is known in the loving.