To “love your neighbor as yourself” is not a restating of “do unto others as you would have them do unto you”, and I thank Christ for the fact, because the Golden Rule — taken as the singular guiding principle of morality — is frightening as all hell.

To “love your neighbor as yourself” is not a restating of “do unto others as you would have them do unto you”, and I thank Christ for the fact, because the Golden Rule — taken as the singular guiding principle of morality — is frightening as all hell.

For a sizable portion of the population, following the Golden Rule involves leaving others alone to drink Jaegermeister and play World of Warcraft. It could consist of treating others with rainbow-puking positivity, in a syrupy effort to provide eternal emotional affirmation. It could very well mean treating others as an object of lust, or even of violence: The masochist following the Golden Rule is scary thought indeed.

We are a perverse race of mammals. There is no guarantee that the way we would like ourselves to be treated has any bearing on whether that way is objectively good.

Now the call to “love our neighbor as ourself” is fundamentally different. Every man has one, and only one, experience of self: Himself. We — creatures of singular consciousness — know only our own thoughts, reactions, yearnings, longing for love, prayers for mercy, experiences of truth, goodness, beauty, etc. We are sure of the depth and richness and fullness of only our own existence. Sure, we can decide that others are having a remotely similar experience of self, but this can only be a decision of faith. We can neither know, nor prove that we are not the only self in existence, for we cannot experience another as a self, but only as an other, as an object outside of ourselves.

This is man’s greatest sublimity and highest absurdity, that despite having assurance of only his self existing, he treats his neighbor as a self. I believe it a thing rarely done, perhaps once in a thousand different interactions, for it is infinitely easier — and far more comfortable — to treat others, well, as others. This is, after all, how they are presented to us. We view this object, this rock, that animal, this baby, that human person. There is a shallow pool in the heart of man that contains only himself, and designates all else others.

In fact, it is often the case that the more someone is revealed as a self, the greater the temptation is to view them as merely an other.

Pornography is probably the greatest example of this impulse. The naked person is exposed, more fully revealed in their body, and thus more fully recognizable as a self. But it’s a terrifying thought that the person pixelated into an infinitely repeated pageantry of lust contains within himself the same doubts and fears of human existence, the same interior life occupied by a longing for love, and that same uniquely human capacity to wake up in the morning with a desire to do good that we have — in other words, that he is a self. Believing this would certainly render mindless masturbation difficult, and so, in the face of the naked person — so vulnerably a self — we reciprocate by treating them as utterly other. The pixels provide a welcome safety net.

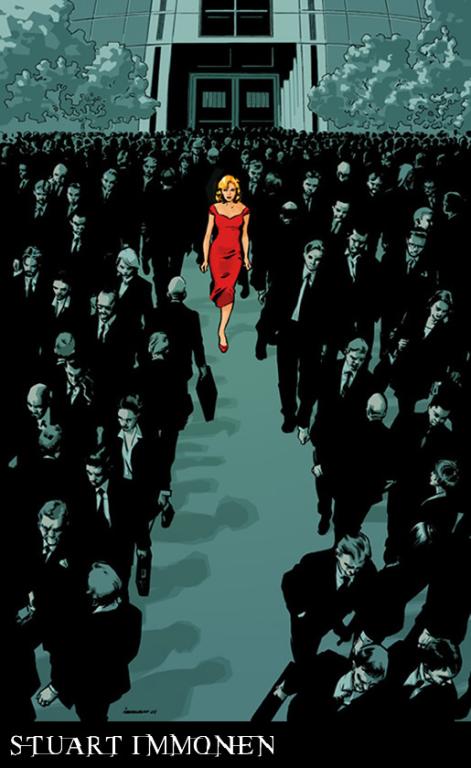

We do this all the time. We will reduce groups of selves to the object “crowd” unless we make the intentional, and difficult, act of faith, and claim that each individual walking in Times Square is an unrepeatable existence to be loved.

We do this all the time. We will reduce groups of selves to the object “crowd” unless we make the intentional, and difficult, act of faith, and claim that each individual walking in Times Square is an unrepeatable existence to be loved.

We reduce selves in moving boxes to “cars”, treating them with all the dignity and respect that a hunk of metal that doesn’t use turn-signals deserves. We create a whole host of labels to objectify selves into groups. The man who opposes the murder of infants is absorbed into the title “pro-life”, the one furious at God’s apparent inactivity in the world into “New Atheist”, the man without money is no longer a man but “the poor”, and so on and thus forth, fulfilling Kierkegaard’s bitter observation that “once you label me, you negate me.”

We are told not to objectify others. It is truly not objectifying others that is the effort, for all it takes to objectify is not to make a leap of faith and treat the other as a self. Objectification is the natural result of an unexamined experience.

Every person you meet, you meet as an object outside of yourself, as an interestingly arranged collection of atoms interacting upon your senses. You have no proof that he is a self. It is natural to treat humans like objects. Thus we categorize human beings, label them, use them orgasm-aiding devices, ignore them, and otherwise make like a dead thing and, without any effort, take the downward stream towards the total objectification of all others.

But blocking our path is that strange demand to love our neighbor as ourself. Love is an action of the human will that, in faith, treats those who can only be experienced as others as selves. This is self-evident. The more you love another, the less concerned you are with their objective qualities — how they appear to you, how they affect you — and the more you are concerned with their subjective qualities, their qualities as the selves that you cannot possibly have proof of them being — how they feel, whether they are at home in the world, their state of being, etc. As Kierkegaard posits in Works of Love:

Who, then, is one’s neighbor? The word is clearly derived from neahgebur [near-dweller]; consequently your neighbor is he who dwells nearer than anyone else, yet not in the sense of partiality, for to love him who through favoritism is nearer to you than all others is self-love—”Do not the heathens also do the same?” [Matt. 5.46f.] …The concept of neighbor really means a duplicating of one’s own self (p. 37).

If a man watching porn were for a moment to love the porn-star he would weep, for in making that absurd leap of faith that treats all others as selves, he would care how she felt, as he cares how he himself feels. If the philanthropist were to see “the poor” as singular selves, he would — by his act of love — cease to be a philanthropist and begin to be a Saint, for a Saint doesn’t give a damn about the poor — he loves his neighbor.

This may be why the sudden death of a loved one is so unbelievable, so vomit-inducing, so utterly rejected by the human mind. The one we have loved, the one we have treated as a self, has died. It follows that we, a known self, in a very real way, experience a death within that death. (When Michael Jackson died it felt far different. He was an other to me.)

There is far more to say on this subject, and I fear that I’ll be doing just that. But for now, lest we vomit Christ’s notable-quotable to “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” onto bumper stickers crowded with the similar sentiments of a multitude of Golden Rule religions, we should remember He said a little more: “Love your neighbor as yourself”, and that this is truly the greatest and most difficult of commandments.