The New York Times article What Happens to Women Who Are Denied Abortion? is an interesting read. The conclusions drawn from it have been — so far — pretty awful.

The New York Times article What Happens to Women Who Are Denied Abortion? is an interesting read. The conclusions drawn from it have been — so far — pretty awful.

This is because, by and large, culture-warriors don’t read. We subsume everything into a pre-ordained, pre-packaged worldview, and use even the most incomplete, unhelpful sociological data as a weapon and a trump card. This particular article, judging by its postings on Facebook, went into the “See, abortion is good for women!” category, but in actual fact — and were we to muster up the balls to say that the quality of human existence is ultimately not judged by sociological standards — the article — quite accidentally — affirms the triumph of life over death, of difficult love over abortion, and puts a jewel in the crown of motherhood.

The study compared women who received an abortion and women who went to receive an abortion but were turned away.

“Women’s depression and anxiety symptoms either remained steady or decreased over the two-year period after receiving an abortion,” and…“initial and subsequent levels of depressive symptoms were similar” between those who received an abortion and those who were turned away. Turnaways did, however, suffer from higher levels of anxiety, but six months out, there were no appreciable differences between the two groups.

This was used to make the assumption that the idea that “women regret their abortions” is wrong. But collecting women’s reactions just after receiving an abortion does not merit this conclusion. If both the women who were denied abortions and the women who had abortions had come to the point in which they desired and deemed it “OK” to have an abortion, the initial, primary experience of not receiving that abortion would be — all things considered equal — disappointment. The denied women were, well, denied. The difficulty they sought to solve via abortion was not solved. The women who received an abortion, on the other hand, avoided a potential difficulty. This is consistent with previous research that found that the overwhelming experience the majority of women of women felt in the first year after their abortion was one of “relief.”

This indicates what we all know, that unintended pregnancy is difficult, that motherhood is difficult, that the situations of poverty that so often lead women to consider abortion in the first place are difficult, and insofar as not killing your child means you have to face those difficulties, then yes, of course “turnaways did…suffer from higher levels of anxiety,” but — and this is part of what I mean when I say that this article is accidentally life-affirming — “six months out, there were no appreciable differences between the two groups.” After a short amount of time, having an abortion will lead to no less anxiety than having an unintended pregnancy.

But I have some major concerns with the article.

In the first place, the study has not been peer-reviewed. There is no public access to the paper to examine the claims. For the New York Times to sandwich a study that may not even be published into an emotional article is a little weird. Secondly, the bias of the study is obvious. It comes from the research group Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH), whose founding member states on their website that she helped create the group because, “I knew it was time to return to my first love, access to abortion care.” (Now obviously this is fine if all the methodology checks out. My issue is the NYT’s premature media ejaculation, which has created a situation in which their article will have it’s emotional effect long, long before the study is published and we can decide whether our emotions were warranted.)

Then I have an issue with looking at the 2-year aftermath of abortion and coming to some sort of general, “abortion is good for women” conclusion. For some women, there is immediate regret. For others, the fact of a “problem solved” is enough to carry them through. But the fact of abortion is not something women deal with for 2 years. It is a lifetime struggle. Looking at initial relief does not appreciate the whole woman, in the entirety of her emotional and physical life. From Leslie, in Virginia, who had an abortion:

Looking back on the choices I made, I didn’t realize the profound emotional impact the abortions would have on my life. I buried them in the deep recesses of my soul, where they stayed for the next three decades. I moved on with life, feeling bogus and unworthy, but strained forward in my motherhood, marriage, career, and community involvement.

Trying to validate my choices, I became a strong pro-abortion supporter and spent many years fighting to protect women’s reproductive rights. I was an outspoken advocate for choice…at times militant with anyone who didn’t agree with my opinion. The radical feminist inside me angrily argued that it was only about a woman’s right to choose.

I even lobbied lawmakers in the Virginia General Assembly, helped organize the Republican Pro Choice Coalition of Virginia, worked as a Media adviser for a Pro Choice House of Delegate candidate, hosted events for Pro Choice candidates, and was one month away from becoming a Board member of the Virginia League for Planned Parenthood when my heart dramatically changed…thank God!

Nearly five years ago, a powerful message clearly came to me that I could no longer fight against the lives of the unborn. God’s grace allowed me to see clearly that life is sacred. I began regretting my abortions and attended a Rachel’s Vineyard Retreat for post-abortive men and women where I finally received the tremendous healing I so desperately needed. I learned to forgive myself and give dignity to the precious lives I took.

This is obviously an anecdote, but it helps me clarify what I mean. Abortion is not a two year issue. It may, as was the case with Lesli, a 35-year issue. The article brushes off the idea that the effects of abortion on women should be studied over a long period of time by saying:

In the National Right to Life’s five-part response to preliminary findings of Foster’s study, which were presented at the American Public Health Association conference last year, the group noted that the ill effects of abortion — future miscarriage, breast cancer, infertility — may become apparent only later. Reputable research does not support such claims.

This might true of those three effects listed, although a 2003 study published in Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey found that “Previous abortion was a risk factor for placenta previa. Moreover, induced abortion increased the risks for both a subsequent preterm delivery and mood disorders substantial enough to provoke attempts of self-harm.” As far as the question of whether women who’ve had abortions are at greater risk for mental health problems, I honestly don’t know what to think. The data swings this way and that way, from nays to yays, from the final answer to other final answers, from including post-abortion syndrome into psychological practices to saying it doesn’t exist.

But I think this is where those trafficking in sociological evidence — on both sides of the issue — miss the point. Barring the times it is forced, abortion is not something that simply “happens” to you, an event for which we can then evaluate the “outcomes.” Abortion is a decision. It is a choice. And the measure of whether a person is at peace with his choice is not a combination of the objective consequences of his choice, even when these consequences are psychological or economical.

For instance, I might choose to marry a woman with cancer. As a consequence, I might experience a decline in every objective standard of “wellness.” I’d shoot below the poverty line with medical bills and far below the normal-anxiety line with worry. I’d lose weight, I’d lose sleep, I’d lose time — and none of this would change whether I believed I made the right choice. The choice stands alone. The question no one is asking is “Would you rather not have married her?” — and yet my answer to this question is the only one that matters. Consequences can certainly influence my view of the choices I make — they do not define my inherent value-judgment on those choices.

So I’d argue that we need to back up. The one question we’re not asking women who’ve been denied abortions is, to my mind, the first question I’d ask: “Would you rather have had an abortion?” This cuts through the sociological back-and-forth, the endless study-rebuts-study game that embarrasses everyone, and asks the question that matters, the question that ultimately defines a persons well-being. It treats women like, well, people.

And as the article points out, when it comes to actually the question that matters, women overwhelmingly affirm the goodness of life over the difficulties of motherhood. Woman S. was denied an abortion.

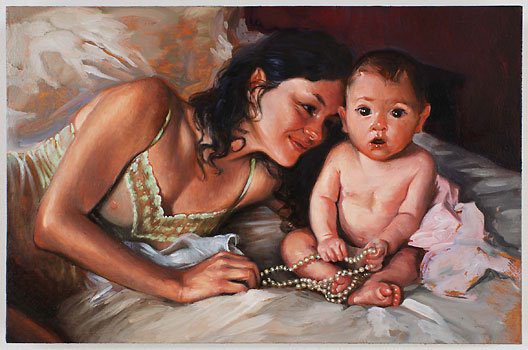

S. now says that Baby S. is the best thing that ever happened to her. “She is more than my best friend, more than the love of my life,” S. told me, glowingly. There were white spit-up stains on her green top. “She is just my whole world.”

When I told Foster S.’s story, she wasn’t surprised that S. ended up bonding with her baby. “That would be consistent with our study,” Foster said. “About 5 percent of the women, after they have had the baby, still wish they hadn’t. And the rest of them adjust.” S.’s experience is also consistent with one of the most striking statistics from Henry David’s Czech study. David found that nine years after being denied abortions, 38 percent of women said they never sought one in the first place.

Which is really beautiful stuff. Granted, this fact will be ignored in favor of the general yodel that “women denied abortions are less wealthy than the women who receive them” — yes, it’s called raising a child, now sit down — but I want to bring it up anyways: After giving birth, 95% of women denied abortions were glad that they did not have an abortion (and I imagine this percent grows over time).

Now can it be said that 95% of women were glad they had their abortion? Actually, according to a criticism of the presentation of the study, in just one week out, 3% of aborting women reported they had made the wrong decision, and a 2000 study found that, by two years, that grew to 28%. I can only imagine that number grows at 5, 10, 20, and 50 years.

So the article somewhat accidentally points to the fact that the vast majority of women who are denied an abortion are ultimately  happy about the fact, while a sizable portion of those who are not denied their abortion, in growing numbers over time, regret having one. And if you’re thinking, “Well duh, who would wish they’d aborted their child 10 years into being a mother?” then I’m happy, because it is rather obvious. The fact of motherhood — even unplanned motherhood, even initially undesired motherhood, even unplanned-undesired-loaded-with-objective-sociological-markers-of-a-difficult-life motherhood — is beautiful, ultimately rendering even the most tempting abortion unthinkable, to the point that “nine years after being denied abortions, 38 percent of women said they never sought one in the first place.” The same cannot be said of abortion. Given the choice between the two, I’d argue for motherhood, that love which seems to overwhelm even the most damning of objective, sociological markers, giving women something they wouldn’t give up for the world.

happy about the fact, while a sizable portion of those who are not denied their abortion, in growing numbers over time, regret having one. And if you’re thinking, “Well duh, who would wish they’d aborted their child 10 years into being a mother?” then I’m happy, because it is rather obvious. The fact of motherhood — even unplanned motherhood, even initially undesired motherhood, even unplanned-undesired-loaded-with-objective-sociological-markers-of-a-difficult-life motherhood — is beautiful, ultimately rendering even the most tempting abortion unthinkable, to the point that “nine years after being denied abortions, 38 percent of women said they never sought one in the first place.” The same cannot be said of abortion. Given the choice between the two, I’d argue for motherhood, that love which seems to overwhelm even the most damning of objective, sociological markers, giving women something they wouldn’t give up for the world.

The study’s only point that seems like a valid 2-year concern was as follows:

Adjusting for any previous differences between the two groups, women denied abortion were three times as likely to end up below the federal poverty line two years later. Having a child is expensive, and many mothers have trouble holding down a job while caring for an infant. Had the turnaways not had access to public assistance for women with newborns, Foster says, they would have experienced greater hardship.

So let’s work hard to make sure new mothers have our support.

For those women who have had an abortion, I realize that the popularity of the NYT article and its subsequent discussion may be painful. I apologize for any insensitivity. Know that I am praying for you.