Poverty is the primordial fact of human existence, for we did not earn our existence — we were given it by our dear, darling parents. All subsequent earning, owning and wealth is contingent upon this being given — upon receiving existence like a welfare check.

But we are poorer still, needy for even after the gift of existence, waiting to be given language, virtue, identity, belonging, continued existence — donations that make all later owning, earning, and wealth possible. The means of becoming fully human are as given like Christmas presents.

If “have” indicates anything amounting to total ownership, we have nothing. Touching the edges of this ontological poverty, feeling its shape and its squeeze, I try and fail to avoid contemplating a possible Giver, a Donor, a Cosmic Sap who presses pennies to the palms of we whose existence is a begging. Yes, my existence was given to me by my parents, and their’s by their parents, and so on and thus forth, but to leave it at this is to wallow in infinite regress, to continuously pass the question of who gives existence back in time. If all existence is given, who first gave?

So language is given to us. Our parents point to the sparrow, give us its name, and we believe them. A child uneducated in speech will not spontaneously develop the capacity for language and linguistic thought — he waits for education. But if we haven’t evolved to simply “become symbol-users ourselves,” if language is given to us by our parents and our community, and to them by others, and to them by others, we arrive at the need for a genesis, a primordial moment in which language — or arguably, rationality itself — was first given, to be ever-after passed down. This idea, the miracle of language’s origins, was part of the immense intrigue that brought Dr. Walker Percy to the Catholic faith.

But this is not the place — if there is any place — to present a demystified argument for the existence of God. I merely wish to point out that there is an inescapable connection between poverty — with its recognition that nothing is owned — and religion. Let those accustomed to sneering sneer. We have heard and will continue to hear religion’s affair with the poor chalked up as a mark against its validity, a metaphysics for idiots, science for the uneducated, a vision of impossible wealth for the broke, the opiate of the masses and a carrot for all the asses for whom life would otherwise be unbearable misery and meaninglessness.

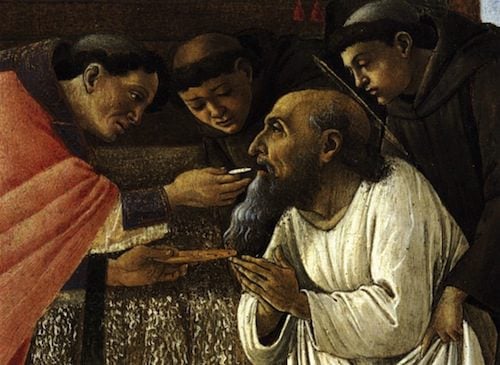

And yes, it is possible that poverty and religion are wed because the poor are largely unenlightened beyond the confines of a mystical, authoritative, and often unintellectual system. But I wonder whether the marriage is not a good deal richer. For if poverty is the truth about human existence, in which all things are given, then the motions and meanings of religion are the proper, intelligible and honest response to the fact of waking up human. Surely we recognize that the universal postures of prayer are identical with those of the homeless man who begs by the gas station? Kneeling, pleading with fingers interwoven, imploring with hands folded, bowing, weeping, rocking, extending open palms — this is the dialect of the poor and the faithful, the common ground between the wealthy churchgoer and the beggar outside the door. Both are engaged in radical honesty about the nature of their existence. This is the dialect of the divine liturgy, a practice in poverty, a gift to the rich man who would be ashamed to kneel on the street, the culmination of which is a soup-kitchen called Holy Communion, where we act out that universal symbol of dependency — receiving food from another. If humans are fundamentally poor, than these religious acts are fundamentally human.

Being materially poor is a physical confession of the universal truth that we have nothing we can call our own. Being materially poor delivers first-hand the reality we have been teasing — that all things are given. Thus being poor presses our faces with messy necessity against the possibility of an ultimate Giver: If I have nothing, and all is given, who first gave? Perhaps the poor live the conundrum of the Uncaused Cause. Perhaps poverty and religion are wed because the poor are blessed with the first-hand experience of a universe in which we cannot entertain the illusion of owning things for ourselves. Perhaps “theirs is the kingdom of God,” theirs the province of a possible Giver, because being poor is being correct, an ontologically honesty that must look towards a Provider, as effects look to a cause.

This, at least, make sense to me, for I understand Christianity as the means by which I fully become myself. I go to church in a desperate attempt to be who I am. If poverty is the truth of existence, the nature of the self that I am, and Christianity is the means by which I become who I am, then of course Christianity is a bended knee and an outstretched palm. It is a becoming poor.