NSFW, but neither is the fact that you’re on this blog at work in the first place.

NSFW, but neither is the fact that you’re on this blog at work in the first place.

Almost anything we can be proud to call American came from poverty. Jeans came from miners, bluegrass from the British immigrants of Appalachia, barbecue was popularized by impoverished Southern Blacks who couldn’t afford expensive cuts of meat, and blues, jazz, and rock n’ roll — those uniquely American art forms I was so proud to hear playing in the bars of Budapest, Vienna, and Rome — rose up from the same. Why? Why not from suburbia or Wall Street?

There’s a plethora of reasons, but here, I think, is the biggie: Poverty is an occasion for community. We are more likely to help each other when we’re not quite making it on our own. The degree to which we shirk self-reliance is the degree to which we start relying on our neighbors. Since culture is always a sharing in the work and life of other men — present insofar as we consent to being made, shaped and formed by a community and a tradition — it makes sense that, historically speaking, it comes from the tight-knit, poor communities. From poverty, community, from community, culture.

But it is almost foolish to bring this up, when so many poor American communities are the most contentious, culturally depraved, anti-communal places on Earth. I cannot, nor should I maintain a romance of poverty walking past the place a 5-year-old was shot in a pathetically theatrical “turf war” between dealers. It’s almost silly to think of the origins of culture rising up from the poorest communities when “whore” is spray-painted across neighborhood doors and no one talks to each other. So what happened?

Consider, as a present example, the current state of hip-hop.

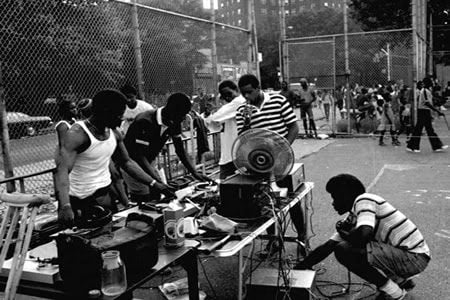

Rap music came from poor, tight-knit community, taking its foundations in the already established tradition of soul music and spoken word poetry. In fact, its origin is the most communal event I can think of — neighborhood block parties in the Bronx. Something by the community, for the community –rhythm, lyric, dance, the neighborhood, the block. Not innocent in its lyric, but based around positive goods — fiery social criticism and a celebration of a being black. Anger and humor in a community downtrodden by slumlords. Party stuff.

Rap music came from poor, tight-knit community, taking its foundations in the already established tradition of soul music and spoken word poetry. In fact, its origin is the most communal event I can think of — neighborhood block parties in the Bronx. Something by the community, for the community –rhythm, lyric, dance, the neighborhood, the block. Not innocent in its lyric, but based around positive goods — fiery social criticism and a celebration of a being black. Anger and humor in a community downtrodden by slumlords. Party stuff.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FTJ6RrQoOxU

Now, in the mainstream, the values it preaches are largely indistinguishable from the values of capitalism and post-Christian, suburban, sexually-liberated, white culture. They’re just pushed to extremes. From it’s new place in the sphere of wealth, not rising up from the poverty and community of the block, but descending down from the immense will to power of the record company, rap music preaches the values of wealth back to the community that is its mother, like a child learning curse words at school and “bringing them into the house.”

50 Cent could say “get rich or die trying,” and what’s remarkable isn’t the shock-value of the phrase, but how comfortably the idea fits in with the impulse and drive of the self-made capitalist. I have heard the same phrase from poor African-American kids and a rich, unbelievably racist Serbian businessman.

Lil Wayne, one of the best examples of a culture perverted and re-sold, can say…

AK on my night stand, right next to that bible

But I swear with these 50 shots, I’ll shoot it out with 5-0

Pockets getting too fat, no weight watchers no lipo

Money talks, bullshit walks on a motherfucking tight rope

…and it’s weird when I have to check if I’m reading Limbaugh or Weezy. The latter’s lyrics parrot the nihilism of neo-conservative, “Christian,” capitalist culture. But it’s not just him — the dominant WASPish American narrative is the dominant narrative of mainstream rap. If you want the American Dream, don’t read books — listen to hip-hop. You’ve got the self-made man ambition:

The places I’m ’bout to go and the money I’m ’bout to see

Gave Bill Gates some binoculars and said, “Look out for ME!”

…

My momma quit her job and now she works with six figures

Cause I’m a self-made nappy headed RICH NIGGA! (T.I.)

You’ve got the Ayn-Randian individualism, the worship of “the word which can never die on this earth, for it is the heart of it and the meaning and the glory. The sacred word: EGO.” There’s a million ego trips I could pick to show this, but let’s cut to the Kanye:

I am a god

Hurry up with my damn massage

Hurry up with my damn ménage

Get the Porsche out the damn garage

But, because rap music is absorbing the dominant culture, you’ve even got the placid use of Christianity along side this worship of self and mammon:

I am a god

Even though I’m a man of God

My whole life in the hands of God

So y’all better quit playin’ with God (Kanye West)

You’ve got the rags to riches narrative that provides the hope and the despair of the vast majority of listeners who will not be rid of rags:

He said: “I write what I see

Write to make it right, don’t like where I be

I’d like to make it like the sights on TV

Quite the great life, so nice and easy” (Lupe Fiasco)

It’s not all bad stuff, but I could go on all day — the ownership of private property, the protest of gun control, distrust of government, business-man values, the constant, panicked assertion of having earned everything one has, it’s all there. Rap is a Republican. And of course, listening to mainstream rappers talk about sex is almost indistinguishable from the dominant values of a “sexually-liberated” white culture, where sex is striving to be separate from fertility, family, responsibility, and community. The difference is that rappers are unintentionally honest in their recognition that sex stripped from family tends towards violence — like the childless, sexy-CEO, pseudo-rape of an Ayn Rand novel.

David Samuels, in his classic 1991 essay “The Rap on Rap,” made the point that rap music descended into a celebration of criminality and violence against women to the degree that it targeted a wealthier, white audience.

The ways in which rap has been consumed and popularized speak of cross-cultural understanding, musical or otherwise, but of a voyeurism and tolerance of racism in which black and white are both complicit. “Both the rappers and their white fans affect and commodify their own visions of street culture,” argues Henry Louis Gates, Jr., of Harvard University, “like buying Navajo blankets at a reservation roadstop. A lot of what you see in rap is the guilt of the black middle class about its economic success, its inability to put forth a culture of its own. Instead they do the worst possible thing, falling back on fantasies of street life. In turn, white college students with impeccable gender credentials buy nasty sex lyrics under the cover of getting at some kind of authentic black experience.”

In 1991, what sold was not black culture, but black culture perverted for the sake of white entertainment. The impossible image of the African-American man that mainstream, gentrified hip-hop sells back to African-American communities — incredibly rich, enjoying drugs like candy, having impossible sex devoid of consequences, depraved and happy — it’s an idol, a life-wrecking idol, not of a culture but against it. What comes out of community and poverty is taken, packaged and re-sold to the detriment of that same community — for how many young men and women idolize these impossible images, not knowing or caring that they’re complex mythologies of marketing?

But 1991 was a while ago. Now, in the 2000’s, the degree to which the culture that came from poor community has been bought, packaged, and sold, transmogrified into the non-culture of fashion, capitalism, individualism — it becomes humorous. Or at least it would be, if it wasn’t for that fact that it is sold back to poor communities disguised as their culture — a subliminal education for the naturally communal poor in how to be spiritually, selfishly rich.

Rap is a good example. But it’s just an example. The phenomenon by which community is killed in the buying, perverting, and selling of the same culture that springs forth from it — it’s everywhere. It’s in the farmer’s market, a cheap, sensible form of shopping that turns into an impossibly expensive trend in the hands of fashion. It’s in sport, a community event if there ever was one, curdling into a vicious, millionaire-making source of Viagra advertisement and shoe sales the moment the consumptive King Midas of non-culture touches it. It’s in beer. It’s in religion. It’s in tattoos and mason jars. The best thing to do — burn the television with fire, get out while you can, or better yet, save yourself by grabbing hold of the Church, that rock of community and culture unmoved by the fads and fashions of the world.