I know it’s hardly with-it to draw distinctions between men and women. And yes, I know humans are androgynous, non-gendered ghosts suffering the misfortune of being smooshed into bodies with gendery bits that delude everyone into thinking: “Look, there goes a dude.” But bear with me, I’m feeling ambitious.

Femininity is more cyclical than masculinity. If the female body is dizzying for men, it is only because it is made out of circles. It cannot be encountered in the same way each day, but requires passive conformity to its present moment. This is obvious in the fertility cycle, wherein women’s bodies gain proportion and claritas in monthly season, where drives, emotions, mental operations, and value-responses ebb and flow, and where pregnancies changes the shape of the body in familiar patterns.

If femininity tends towards circles, masculinity tends towards lines. Again, the body gives us a few hints. Where the female body curves, the male body straightens, where the former swells, the latter flattens. While the male body can certainly change — gaining weight, losing hair — it does not reveal itself as an essentially cyclical phenomenon. The distinction between masculine and feminine time, then, begins with this distinction between progression and season — between the line and the circle.

Our age has a perverse obsession with progress, with driving-forward, with moronic catch-phrases like “a lack of progress is regress” and “time is money,” with the destruction of environmental cycles and human traditions, with ignorance of the past and an absurd optimism in an ever-improving future, in which everything improves (usually through technology) on a forward-march incapable of looking back. Our age, in short, lives a hyper-masculinized vision of time.

The line is the god of an industrial and technological age, of a culture that thinks in straight-edges about tasks comprised of a start and a finish. It defines time as the duration between event A and event B. In principle, it is a useful working definition. Taken out of the workday world in order to serve as the truly human view of time, however, and the line becomes a relentless plowing-forward of the present moment into a formless future that leaves behind a wake of detritus we call “the past.” This is the optimism of Winston Churchill, who promised that “there will stretch out before you an ever-lengthening, ever-ascending, ever-improving path.” It is also the pessimism of our modern artists and philosophers, who exist in the panic of a constant break from “event A,” frantic with the need to split from tradition, jittery in their rush towards “event B.” And it is, in the final estimation, and inadequate view of the human experience of time, which does simply plow forward, but remembers, recalls, returns, anticipates, and hopes.

The line is the god of an industrial and technological age, of a culture that thinks in straight-edges about tasks comprised of a start and a finish. It defines time as the duration between event A and event B. In principle, it is a useful working definition. Taken out of the workday world in order to serve as the truly human view of time, however, and the line becomes a relentless plowing-forward of the present moment into a formless future that leaves behind a wake of detritus we call “the past.” This is the optimism of Winston Churchill, who promised that “there will stretch out before you an ever-lengthening, ever-ascending, ever-improving path.” It is also the pessimism of our modern artists and philosophers, who exist in the panic of a constant break from “event A,” frantic with the need to split from tradition, jittery in their rush towards “event B.” And it is, in the final estimation, and inadequate view of the human experience of time, which does simply plow forward, but remembers, recalls, returns, anticipates, and hopes.

It is no accident that an age that treats time as a line treats the female body with similar violence. It is no accident that an age which has steamrolled the delicate ecological cycles sustaining our environment in favor of linear profit and progress also demands a masculinization of the female body via menstrual suppression, the impossible androgyny of female fashion, the lack of decent maternity leave, and our generally abysmal devaluation of pregnancy, motherhood and breastfeeding. The basic message a woman hears is: “Destroy the seasonal. Take up the linear.” But if femininity is suppressed, it is not just at the expense of women, but at the expense of men, who have no education in a seasonal life, no natural, beautiful, and therefore desirable check on the temptation to plow forward, to endlessly assert, to pretend that constantly making a living will ever amount to a life.

This view might prove difficult to an age that views man and women as mutual competitors for individual, androgynous happiness, but the masculine image of time, in its drive forward, needs the feminine in its cycle. We don’t have the space to argue what ought to be an obvious point, that the human person is that type of being that only exists in and through gender-communion, but take it as a doctrine: The feminine and the masculine are not the exclusive property of women and men — they are modes of being-in-the-world that each may participate in. If women hold femininity as their very form, and men masculinity, they hold it as a gift for the other, as a responsibility to educate the other to rise to the fullness of their humanity. Women give by way of communion the femininity men lack by way of nature, and vice versa. To be gendered is to be-for-the-other.

For what mightier check, what stronger hold is there on violence — that great temptation of masculinity — than season? Our World Wars made remarkably efficient use of industry and technology (triumphs of progress and linearity) to plunge violence for its more unimaginable possibilities. And yet, in 1914, on the Western Front of the First World War, there was a week of profound peace. British, French and German soldiers met in No Man’s Land. They exchanged gifts. The sang songs. The played football.

It was Christmastime. Season asserted herself with a strength that puts violence to shame, saying, quite simply: Now is not the acceptable time for war. It is time for peace. While this miracle was certainly driven by piety, I cannot help but view as a fundamentally human reality, tied not just to the particular facts of the Birth of Christ, but also to the proper incorporation of the seasonal-feminine into an linear-masculine horror of assertion and violence.

An atemporal victory of masculinity over the principle of femininity is no victory. A life without history, without children, without cyclical rest, without season, just the daily, masturbatory existence of constant acquisition, the “ever-expanding path,” and the forward-march — this uneducated masculinity is as much a source of impotence, rage and violence as it is of millionaires, and could as easily end in prolonged video-gaming as becoming a CEO.

Now it is far more difficult to speak of what the masculine form offers the ecological form of femininity, for while I daily receive an education from the latter, marvel at the fact, and can attest to its reality — women are awfully quiet about whether men are doing them any good. But if I were to venture a guess, I would say that the masculine form is a pedagogy in teleology — a lesson in achieving an end. It is written in the very muscular structure of the male form, to accomplish the task, to complete the mission, to do and do well, to use strength.

In the creation myth of Judaism, when Adam and Eve were cast out of the garden of Eden, their punishments mirrored this bodily reality. Eve is given the suffering of cyclical pain –“I will intensify your toil in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children” — and Adam is given the suffering of constant toil:

By the sweat of your brow

you shall eat bread,

Until you return to the ground,

from which you were taken;

For you are dust,

and to dust you shall return.

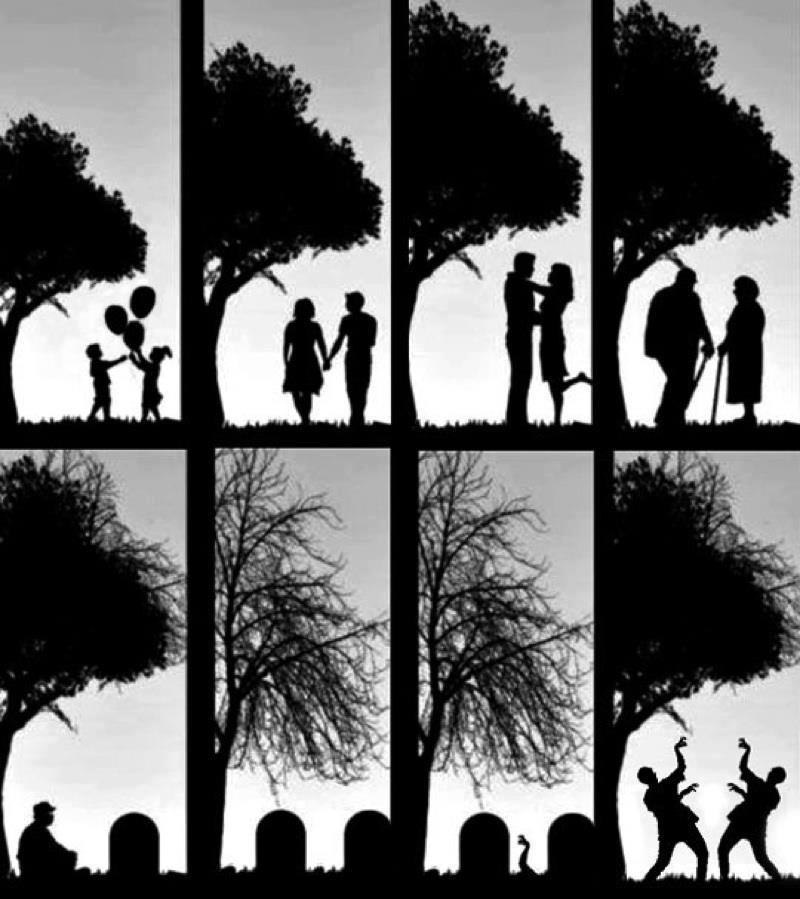

Adam, not Eve, is reminded of his own death, of the “end of the line” and the final collapsing of his body into dust. Surely this is a necessary check on a purely cyclical vision of time. Things return, seasons cycle, planets orbit, yes, but in the end everything really and finally dies — and you most of all. Talk of “the circle of life” works well enough in the Lion King. When you are staring at the suited corpse of your friend, it becomes a shallow comfort to imagine the process by which his atoms will be reconstituted into a patch of stinging nettles. He is gone, and even if he fertilizes the grass, which feeds the deer, which feeds the hunter, who has a baby, there is no he in any of these things. I sympathize with the pathos behind books like “Be a Tree; the Natural Burial Guide for Turning Yourself into a Forest,” but why make nature an angel? If I can become a forest, why not the paper that becomes the next Mein Kampf ?

Adam, not Eve, is reminded of his own death, of the “end of the line” and the final collapsing of his body into dust. Surely this is a necessary check on a purely cyclical vision of time. Things return, seasons cycle, planets orbit, yes, but in the end everything really and finally dies — and you most of all. Talk of “the circle of life” works well enough in the Lion King. When you are staring at the suited corpse of your friend, it becomes a shallow comfort to imagine the process by which his atoms will be reconstituted into a patch of stinging nettles. He is gone, and even if he fertilizes the grass, which feeds the deer, which feeds the hunter, who has a baby, there is no he in any of these things. I sympathize with the pathos behind books like “Be a Tree; the Natural Burial Guide for Turning Yourself into a Forest,” but why make nature an angel? If I can become a forest, why not the paper that becomes the next Mein Kampf ?

Perhaps the male form, in its linearity, in its strength, and in its movement towards an end, is a memento mori for a feminine view of time, a check on a cyclical feeling for time, one which whispers, “But there really will be an end, a final breath, a no-more, and beyond this there is no return, and no cycling back.”

This has its resonances in the sexual act, and indeed, I am not unaware of the obvious genital imagery in associating “the line” with the masculine and “the circle” with the feminine. The French refer to the orgasm as la petite mort, literally, “little death,” and death has traditionally been used to describe the male orgasm in English literature, with double-entendres like Shakespeare’s in Much Ado About Nothing, — “I will live in thy heart, die in thy lap.” That it is the male and not the female orgasm that is more often associated with death certainly has to do with the fact that men experience a “refractory period” immediately after orgasm, a period “when a man cannot reach excitement, plateau, or orgasm through any kind of sexual stimulation.” Men die, empty themselves. Women receive, and turn that death into new life. Neither form of sexuality makes sense without the other.

So the line is a reminder of death — insofar as it really is a line, and not an endless continuum — the circle is a reminder of new life, and the marriage of the two gives birth to a properly human vision of time. Thus Christianity asserts herself as a vessel of realism: The Church preaches death and resurrection. Not death that merely looks like death and really amounts to the movement of atoms from the cooling body into the tree — no, real death. The end of the line in all its severity. But here, at the end of all things, resurrection, surprising as a newborn baby, a turning of death into life, a rising-from earth, an ecological vision of rebirth, a lesson we learn from the feminine form — that life comes around again. Not a life that removes the Christian from having to undergo death, not a circle that forgets the line, but a circle that acknowledges the line it is destined to encapsulate. The line and the circle, not in mutual competition, but in harmony, husking off the false shell of either/or, giving birth to the typically catholic both/and of death and resurrection — this is what Christianity offers.