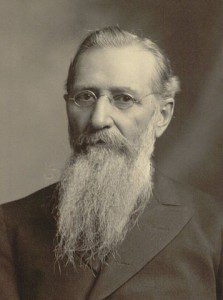

The general thrust of my research over the next few years will be science, religion, and history, centered around evolution and scriptural interpretation. I’ll post various things from time to time. The following comes from The Juvenile Instructor, Vol XLVI No. 4 (April 1911): 208-9. BYU had just undergone a controversy of sorts about evolution, the nature of the Bible, and some other intertwined issues. See my post here. Writing in the Church’s magazine, President Joseph F. Smith, in the 10th year of his presidency, penned the following. I have broken up some of the paragraphing for readability, and bolded some interesting bits, commentary at the end.

SALT LAKE CITY

APRIL, 1911Philosophy and the Church Schools.

Some questions have arisen about the attitude of the Church on certain discussions of philosophy in the Church schools. Philosophical discussions, as we understand them, are open questions about which men of science are very greatly at variance. As a rule we do not think it advisable to dwell on questions that are in controversy, and especially questions of a certain character, in the courses of instruction given by our institutions. In the first place it is the mission of our institutions of learning to qualify our young people for the practical duties of life. It is much to be preferred that they emphasize the industrial and practical side of education. Students are very apt to draw the conclusion that whichever side of a controversial question they adopt is the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth ; and it is very doubtful, therefore, whether the great mass of our students have sufficient discriminating judgment to understand very much about some of the advanced theories of philosophy or science.

Some subjects are in themselves, perhaps, perfectly harmless, and any amount of discussion over them would not be injurious to the faith of our young people. We are told, for example, that the theory of gravitation is at best a hypothesis and that such is the atomic theory. These theories help to explain certain things about nature. Whether they are ultimately true can not make much difference to the religious convictions of our young people. On the other hand there are speculations which touch the origin of life and the relationship of God to his children. In a very limited degree that relationship has been defined by revelation, and until we receive more light upon the subject we deem it best to refrain from the discussion of certain philosophical theories which rather destroy than build up the faith of our young people.

One thing about this so-called philosophy of religion that is very undesirable, lies in the fact that as soon as we convert our religion into a system of philosophy none but philosophers can understand, appreciate, or enjoy it. God, in his revelation to man, has made His word so simple that the humblest of men, without especial training, may enjoy great faith, comprehend the teachings of the Gospel, and enjoy undisturbed their religious convictions. For that reason we are averse to the discussion of certain philosophical theories in our religious instructions. If our Church schools would confine their so-called course of study in biology to that knowledge of the insect world which would help us to eradicate the pests that threaten the destruction of our crops and our fruit, such instruction would answer much better the aims of the Church school, than theories which deal with the origin of life.

These theories may have a fascination for our teachers and they may find interest in the study of them, but they are not properly within the scope of the purpose for which these schools were organized.

Some of our teachers are anxious to explain how much of the theory of evolution, in their judgment, is true, and what is false, but that only leaves their students in an unsettled frame of mind. They are not old enough and learned enough to discriminate, or put proper limitations upon a theory which we believe is more or less a fallacy. In reaching the conclusion that evolution would be best left out of discussions in our Church schools we are deciding a question of propriety and are not undertaking to say how much of evolution is true, or how much is false. We think that while it is a hypothesis, on both sides of which the most eminent scientific men of the world are arrayed, that it is folly to take up its discussion in our institutions of learning; and we can not see wherein such discussions are likely to promote the faith of our young people.

On the other hand we have abundant evidence that many of those who have adopted in its fulness the theory of evolution have discarded the Bible, or at least refused to accept it as the inspired word of God. It is not, then, the question of the liberty of any teacher to entertain whatever views he may have upon this hypothesis of evolution, but rather the right of the Church to say that it does not think it profitable or wise to introduce controversies relative to evolution in its schools. Even if it were harmless from the stand-point of our faith, we think there are things more important to the daily affairs of life and the practical welfare of our young people. The Church itself has no philosophy about the modus operandi employed by the Lord in His creation of the world, and much of the talk therefore about the philosophy of Mormonism is altogether misleading. God has revealed to us a simple and effectual way of serving Him, and we should regret very much to see the simplicity of those revelations involved in all sorts of philosophical speculations. If we encouraged them it would not be long before we should have a theological scholastic aristocracy in the Church, and we should therefore not enjoy the brotherhood that now is, or should be common to rich and poor, learned and unlearned among the Saints.

Joseph F. Smith.

A few observations, then.

- Smith does not pass judgment on evolution directly, but observes that it is an open and disputed theory which does not lend itself to practical, daily needs, and therefore doesn’t belong in Church schools.

- However, he states that many who adopt evolution refuse to accept the Bible as the word of God. This can be read several ways, and I don’t think this is accurate today, even if it was then. However, since Smith also asserts that the Church has very little revelation about the nature of creation or the relationship of God to his children, it does not seem that he reads Genesis/Moses/Abraham as strongly controlling scientific/historical accounts. (Which raises the question, where does his son Joseph Fielding Smith get that from?)

- Smith is pessimistic about the the ability of students to wrestle with ambiguous questions and theory without doing harm to faith.

- Smith is wary of any kind of de facto intellectual class distinctions being established among LDS. This, I think, was inherited from Joseph Smith, and was anti-intellectual in a way. Joseph Smith had bad experiences with trained pastors and preachers, and taught fairly strongly that you did not need training for the ministry.On the other hand, he also engaged in “academic” pursuits like studying Hebrew and German, reading Josephus, etc. (On Josephus, see here, a good LDS lecture here, and the expanded publication of that and similar lectures.) The Church seemed to inherit the suspicion of a trained, quasi-priestly class, as reflected above. This suspicion, I think, is still around today, but has also partially been overcome (see Elder Ballard’s important comments about consulting scholars) and partially been realized in an academic and practical sense by BYU’s RelEd department and CES, respectively.

An interesting document from 1911.