The following is a repost by kind permission of Trevin Wax and his blog.

Work and the Church: A Conversation with Gene Veith & Ben Witherington (Part 1)

By Trevin Wax on Jun 21, 2011 in Interviews | Edit |  Print This Post | Share (Twitter, Email, Facebook)

Print This Post | Share (Twitter, Email, Facebook)

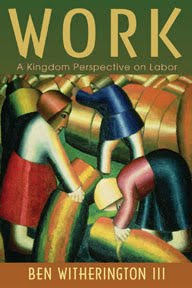

Not too long ago, I was reading a new book by Ben Witherington entitled Work: A Kingdom Perspective on Labor

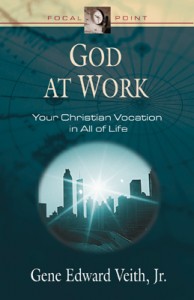

Not too long ago, I was reading a new book by Ben Witherington entitled Work: A Kingdom Perspective on Labor. Midway through the book, I saw that Witherington was interacting with Gene Veith’s book, God at Work: Your Christian Vocation in All of Life in order to underscore the differences between their perspectives.

I had read Veith’s book several years ago and had found it to be a helpful guide to thinking about matters related to a Christian’s view of vocation and calling. It struck me that Witherington and Veith, though working from different theological streams, weren’t as far apart as it seemed.

When I finished the book, I decided to bring Dr. Veith and Dr. Witherington together on this blog and host a forum on how our theological persuasions affect our view of labor. Within hours of throwing out the initial question, the emails from these two brilliant men had piled up so fast and furiously that I found I had to just get out of the way! By the end of the email conversation, I was satisfied that some good discussion had taken place and some differences had been hashed out.

After the conversation took place, Dr. Veith recommended that I break the conversation into separate posts in a series. He then wrote:

“I myself have gotten a lot out of this exchange. It happens rarely enough, for people who disagree with each other in their publications to talk it out, to the point of finding at least some underlying agreements after all. A blog actually makes it possible for this to happen, though few bloggers go to the trouble of using their forum in this way. I really appreciate your doing this. This could be a model for others to follow!”

I hope so, which is why I’m happy to devote the next couple of days to allowing Kingdom People readers enjoy an important conversation about work from two scholars who have spent many hours considering these matters.

WAX: What role does the church play in relation to a man or woman who is seeking to discern God’s call to a particular vocation?

WAX: What role does the church play in relation to a man or woman who is seeking to discern God’s call to a particular vocation?

VEITH: I think that the church’s main role is, quite simply, to teach the doctrine of vocation, according to its own theological light.

As Dr. Witherington says in his book, this is a topic that has been neglected by churches, despite how much the Bible teaches about the topic and despite the huge role that work plays in people’s lives today.

After that, the man or woman struggling over questions of vocation simply needs to be encouraged to see God’s hand in the normal processes and decision-making that goes into finding a job. Dissatisfaction with what one is currently doing, particular interests and talents, opportunities that arise, doors that open and doors that slam in your face – all of these are factors in going in one direction or another. Christians are still subject to all of these “secular” factors, but, through the eyes of faith, they can trust in God’s leading.

WITHERINGTON: I would say from the outset we need to distinguish between being called by God and some particular vocation. So calling and ‘vocation’ should be distinguished.

I certainly think the church has an obligation to help persons discern the call of God on their lives at this or that point in time in their lives. But a person can be called to a variety of tasks on a variety of occasions for a variety of ways of serving the Lord and edifying others. As, you will have deduced from my book entitled Work, I don’t really agree with either Luther’s two kingdoms approach, nor the subset of that, the notion that we are called to some specific vocation over the long haul (e.g. one to be a plumber one to be a preacher etc.)

VEITH: I certainly agree that “vocation” includes much more than the work one does to make a living. We have vocations – a term that is simply the Latin form of “calling” – in the family, the church, and the culture as a whole, as well as in what Luther called “the common order of Christian love” (the ordinary course of life outside of any particular office, the realm of the Good Samaritan, of friendship, and informal interactions).

In fact, Luther considered the things we do to make a living under the classification of the family, specifically “the household” (oikos, which is where we get the word “economy,” from oikonomia, the laws of the household). In Luther’s day, economic activity and the family were not separated as they have been since the Industrial Revolution. Most of Luther’s writings about vocation (as well as those of the Apostle Paul) had to do not so much with “economic activity” as with marriage and parenthood.

That the word “vocation” has narrowed to mean “employment” may be one of the reasons the larger theology of vocation has been lost.

WAX: Why and when do you think the doctrine of vocation became lost?

VEITH: I suspect part of the reason is that it became “hardened.” I believe the Puritans started using the term more or less exclusively for “employment.” The notion that a person has one and only one calling in that sense, so that one must not leave one’s job or improve one’s social status may have the same derivation.

Luther sometimes talks about being satisfied in one’s calling, however lowly in the eyes of the world, but that is not the same thing. In Luther’s time, in the late Middle Ages, social position was very static. But that would soon change, largely due to the Reformation and the doctrine of vocation, as Max Weber argues, leading to the unprecedented social mobility of the Reformation countries.

That vocation is not static and that vocations (in the sense of “callings,” which is what the word means – we could just as easily retire the term “vocation” and retain “calling”) is proven in the most fundamental of the vocations: the family. A person comes into a family with the vocation of a child. She then grows up and is led into the new vocation of marriage. She may then be called into motherhood. And eventually grandmotherhood.

The same thing happens in the workplace (Luther’s father was a peasant farmer, who then became a miner, who then purchased smelting machines and had a small business), including the ministry (Luther was a law student; then he became a monk; then he became a priest; then he became a professor; etc.).

WAX: But Dr. Witherington, you mean something else by “vocation.” Can you elaborate?

WITHERINGTON: Yes. Being a child is not vocation, not least because it does not involve a choice. It’s simply a phase or condition in life.

Is marriage a vocation? Well no, it’s a charisma as Paul calls it in 1 Corinthians 7. It’s something one must have the grace gift to do, but it’s not a vocation. I would say the Greek term charisma (literally grace gift), which Paul then applies to the gift of being single or the gift of being married in the Lord, connotes something quite different from vocation. It has more to do with whether one has the capacity for marriage or singleness, not whether one has the calling to be married or sees marriage as a vocation.

WAX: So how do you distinguish between “calling” and “vocation”?

WITHERINGTON: When the term “calling” comes up in the New Testament, it is applied to becoming a disciple of Jesus, not taking on a particular role or task in the family or in society.

I think I understand why Luther goes the way he does with the language of vocation. Precisely because of his two kingdom theology, he nonetheless wanted to avoid not only the idea that God was only involved in one realm, but he also wanted to avoid the notion that what happened in the other realm was merely secular in character, hence this theological notion that even mundane tasks or even normal familial roles which have nothing necessarily to do with being Christian, are seen as vocations in a rather specifically Christian sense of the term.

If there is one thing that is clear to me about Paul’s use of the term charisma, he applies it only to Christians – to himself and to his converts. I don’t think non-Christians having a calling or vocation in the Christian sense, at least according to the New Testament. They simply have roles and jobs etc.

VEITH: But what about Paul writing this:

“Only let each person lead the life that the Lord has assigned to him, and to which God has called him” (1 Corinthians 7:17).

This is a key text for the doctrine of vocation, which, again, simply means “calling.” This comes in the midst of Paul’s discussion of marriage and singleness, slaves and masters, circumcised and uncircumcised – thus, the “assignments” and “callings” of family, economic activity, and ethnicity.

So you are defining vocation solely in terms of what we have a choice to do? You don’t think our family background or our citizenship are part of our calling? It sounds like you are limiting “calling” to “vocation,” in the sense of economic employment, but you have been arguing against that!

We are certainly getting somewhere, though, in isolating where we disagree. “Vocation” in the Lutheran sense includes “phase and condition of life.” It also is related to the gifts that God gives us. In fact, our different vocations are gifts of God. And the gifts God gives us, in the sense of talents, etc., are part of God’s equipping us for our particular avenues of service (as evident with Bezalel in Exodus 35:30-36:2). These gifts are not to be confused with the spiritual gifts given to Christians, as you discuss, but God gives many different kinds of gifts.

WAX: The main difference between your approaches is that Dr. Veith’s book God at Work applies Luther’s doctrine of vocation, while Dr. Witherington’s book takes on the issue as an Arminian. Of course, there are going to be differences.

VEITH: But I’m not sure we disagree as much as it first appears. Arminianism does have more space for human agency than Lutheranism, Augustinianism, and Calvinism. But there are important differences between Luther, Augustine, and Calvin. We Lutherans affirm the secular world more than Augustinians do. (In Augustine, the City of God and the City of Man are opposed to each other; in Luther, the Two Kingdoms are both under God’s rule and are both inhabited by Him.) And we are not nearly as deterministic as Calvinists. Lutherans do believe in human agency.

As it applies to vocation and to work, when we follow God’s commands and use our work to love and serve our neighbors, we are co-operating with God’s work and His creativity. We often, though, sin in our vocations, working only for our selves and sometimes harming and misusing our neighbors. Nevertheless, God can use even the work of sinners to care for His creation, though some sin against neighbors is so extreme that nothing is left of God’s will.

God never calls anyone to sin. Not all economic activity is a calling from God because not all economic employment involves loving and serving one’s neighbor; rather, it may involve hating and hurting and corrupting one’s neighbor. Being a pimp or a pornographer or an abortionist or a Nazi guard are not callings from God.

(Ben, you would add being a soldier, since you are a pacifist. I would disagree, but I would agree that casino workers do not love and serve their neighbors, but rather take money from their neighbors that should be going to their families, and so that is not a true calling from God. )

Sometimes the issues are not clear–can I love and serve my neighbor by being a telemarketer? a bonds trader?–but these are the moral issues that Christians must struggle with, and, as you say, put God’s commandments uppermost.

WAX: We’ll continue this discussion tomorrow and talk specifically about “cooperating with God in our work”.

Co-operating with God in our Work: The Witherington/Veith Discussion Part 2

By Trevin Wax on Jun 22, 2011 in Interviews | Edit |  Print This Post | Share (Twitter, Email, Facebook)

Print This Post | Share (Twitter, Email, Facebook)

Yesterday, I posted the first of a three-part series prompted by Ben Witherington’s new book, Work: A Kingdom Perspective on Labor. Witherington is professor of New Testament at Asbury Seminary. Gene Veith is the provost and professor of literature at Patrick Henry College and author of God at Work: Your Christian Vocation in All of Life. Today, the conversation between these two scholars (one Wesleyan and the other Lutheran) continues.

WITHERINGTON: Let’s take one of these issues where we really do have a difference. While I am not going to suggest that human beings, Christians in particular, never are co-operating with God in some sense, I am going to insist on is that there are plenty of times where we have been graced and empowered to do things for God. We are the hands and feet of Jesus. Doubtless he could have done it without us, or by using others, but Gene, he’s decided to do it by empowering you and me, for example.

Now what this in turn means is that while I am happy to talk about God empowering or leading or guiding such activities, at the end of the day, they would not happen as my action, unless I decided to do it and acted on the decision. The matter was not fore-ordained, and so I am not merely going along with what God is doing, without God coercing me (and so ‘freely’ in the Edwardsian sense of not compelled to do it), I am actually acting as a free agent of God, and indeed God will hold me responsible for my behavior, accordingly. He will not be holding himself responsible. I bring this all up because it affects the way we look at the notion of vocation and the notion of calling, as we can discuss further in due course.

VEITH: Ben, I think I agree with your first paragraph.

I’m not sure I fully understand your second paragraph. (Do you mean “with God coercing me”?) Is it that you are bringing “free will” into the doctrine of vocation, as with the Arminian doctrine of salvation? As a Lutheran, I can actually agree with much of the former without agreeing with the latter. (Luther wrote “The Bondage of the Will,” but he also wrote “The Freedom of the Christian,” in which he develops his theology of vocation.)

I guess the main difference would be that we Lutherans might have a greater emphasis on sin in the human agency that we do have.

Say a man has the calling to work in a bank. He lends people money and takes care of other financial needs of the community, so that he is indeed loving and serving his neighbors. God is in what he does. But one day he decides to embezzle money. He is stealing from his neighbors. He is certainly free to do that, but God will indeed hold him responsible. Perhaps then he goes to church, hears a sermon from God’s Word, and is convicted of his sin. He repents and puts the money back before anyone notices. From that time on, he works as an honest employee. He has the agency to do that also, though we would say the credit for his repentance goes to the Holy Spirit working through God’s Law. Now that he is doing what he should, does he earn merit for that before God? Well, not really. He is now doing what he was supposed to do all along. ”When you have done all that you were commanded, say, ‘We are unworthy servants; we have only done what was our duty.’” (Luke 17:10). The man, however, assuming he is a Christian, is in the process of being sanctified. The struggle with sin, finding forgiveness, and doing what is right made him grow in his faith, which bears fruit in good works, and so he has grown in sanctification. (Vocation is where sanctification happens. You make that point too, associating our work with our sanctification, but you seem to think Lutherans don’t believe that. We do!)

WITHERINGTON: Interesting. I don’t think a banker has a calling to be a banker in the Biblical sense of the term calling, but let’s leave that aside for a moment. A big part of my objection to what you write about work is the Lutheran understanding of God’s involvement in human work, that He uses human beings as His instruments and is somehow “hidden” in vocation.

VEITH: What would you say to the atheist father who refuses to let his family say grace before a meal because “God didn’t provide this food! I did!” Aren’t we right to thank God for our food because He “gives us this day our daily bread” through the instrumentality of farmers, bakers, and the person who prepared our meal? Isn’t it true that God creates new life through the instrumentality of mothers and fathers; that is, in vocations of parenthood? It is surely true, as I believe you said in your book, that the Holy Spirit is active in pastoral ministry, when the pastor preaches God’s Word and gives spiritual care to the congregation.

I totally agree that the farmer who grew the grain that went into my daily piece of toast and my mother and father who brought me into existence have their own identity and their own moral agency. They can resist God’s will or they can co-operate with Him. Nevertheless, isn’t there some sense in which God is active in their work?

I do not understand God’s presence and activity in human work in a deterministic or even Calvinistic sense, as I believe you are assuming.

WITHERINGTON: The question is: in what sense is God involved in what I do or others do? Does it involve his permissive will or his active will, and if the latter in what sense and in what way?

I see God as a guider, a giver of wisdom, an empowerer, in such situations. I see God as a lover and a persuader. I don’t see him as ‘doing’ the activity itself. God gives us our daily bread through the hands of human beings. We can talk about God setting up the world and the economy and the crops in such a way that it is possible for human hands to make bread and me to buy it. But it is not God who is directly baking the bread or selling it to me. If that is not the case, then I don’t really understand what it means to say We are co-operating with God when we buy daily bread.

VEITH: We don’t co-operate with God when we buy our daily bread. But when we make a loaf of bread and give it to someone who is hungry, yes, we are co-operating with God.

No, God doesn’t do it “directly”. But God’s normal way of doing things is through means. Usually physical means. God doesn’t have to use physical means–he can certainly do things directly, as with miracles and with giving the children of Israel their daily bread directly with the manna in the desert–but he usually works through His created order. (I suppose some of this is distinctly Lutheran, as in our emphasis about how God conveys His gospel in the water of Baptism, the bread and wine of Holy Communion, the paper and ink and soundwaves of God’s Word, but surely we can agree that God is active in His creation, including in non-miraculous processes. We don’t want to be Gnostics.)

One of the great virtues of your book is to break down the dichotomy between the sacred and the secular. Doesn’t limiting God’s action to direct, “spiritual” things and not also to ordinary material life put up that wall once again?

WITHERINGTON: I guess my problem is with the word co-operating. To my Wesleyan ears that sounds like ‘God makes you an offer you can’t refuse’ – turning God into the Godfather. Honestly, I have read a lot of Luther including the Bondage of the Will and I must say I much prefer you and modern Lutheran theologians to Luther! Luther frequently sounds to me more Augustinian than either Augustine or Calvin, especially in the Bondage of the Will, more deterministic, and with less of a proper sense of second causes, and when he starting talking about the Devil being God’s Devil whom he has pre-programmed, I break out in rash, because at the end of day, in too many places, Luther sure seems to be making God the author of evil.

VEITH: Well, thanks for the compliment! It took Luther a long time to break out of his Augustinian monastery.

Lutheran theology is defined not by the writings of Martin Luther, as such – the man was mind-bogglingly prolific, churning out tons of often contradictory material throughout his life as his theology developed – but by the Book of Concord, the collection of confessions of faith from the early Creeds through the Reformation confessions by Melanchthon and Chemnitz to the Catechisms. I’m pretty sure that my formulation is that of the Small Catechism and the Large Catechism, both by a kinder and gentler Luther.

That’s a great and humorous line, that Luther in the Bondage of the Will is more Augustinian than Augustine! In Luther’s defense, a lot of these writings are undecipherable apart from their polemical contexts and Luther’s love of paradoxes, not to mention his not necessarily commendable desire to shock the scholastics and the humanists. He is also doing things with what he called “the theology of the Cross,” as opposed to “the theology of Glory,” which is a subject unto itself, but in which he really tears into both the scholastics and what would become Calvinism (which you should appreciate)! You’ve got to balance the Bondage of the Will with The Freedom of the Christian.

The thing is, Lutheranism often gets conflated with Calvinism. Even though Lutherans tend to treat Calvin as their major theological adversary! Part of the problem is that Calvinists claim Luther for themselves, so that much of what people hear about Luther comes through Calvinist filters! Lutherans actually agree with Wesleyans in affirming the Universal Atonement, that it is possible to lose salvation, and in rejecting double predestination.

WITHERINGTON: I’m glad to hear all this, but it’s not the Luther I remember. Nor the Luther I learned about from Roland Bainton either. If you think Luther was voluminous you should try and read Wesley, even just all his journal and sermons and tracts, never mind his zillion letters. I think he and Luther could compete in the most words in print contest.

VEITH: How were these guys able, with their quill pens and candle light, to be so much more productive than we are, with our computers and electricity? And on top of all of their writing, they were preaching nearly every day of the week! And doing lots of other things, like meeting with people, counseling, travelling, and trying to solve intractable problems. There is an example for us of ”work.”

WAX: We’ll continue this discussion tomorrow and focus on the place of rewards and virtue when it comes to work.

Rewards, Virtue, and Work: The Witherington/Veith Conversation (Conclusion)

By Trevin Wax on Jun 23, 2011 in Interviews | Edit |  Print This Post | Share (Twitter, Email, Facebook)

Print This Post | Share (Twitter, Email, Facebook)

This is the last of a three-part series on work, featuring a Wesleyan theologian (Ben Witherington) and a Lutheran theologian (Gene Veith). In this post, these two scholars focus on the implications of their theological moorings when it comes to good works. (Check out part 1 and part 2 of the conversation.)

This is the last of a three-part series on work, featuring a Wesleyan theologian (Ben Witherington) and a Lutheran theologian (Gene Veith). In this post, these two scholars focus on the implications of their theological moorings when it comes to good works. (Check out part 1 and part 2 of the conversation.)

WITHERINGTON: Why do both Jesus and Paul talk about rewards in heaven or in the Kingdom, and the lack thereof for those who are less profitable servants, shall we say? Do you think virtue is its own reward, and how does virtue relate to your notion of vocation or calling?

VEITH: Of course we are rewarded. God awards abundantly. And I have no problem with the notion of the great saints, the true heroes of the faith, will receive a greater reward than someone like me, though we are also told that the first will be last and the last first and that there will be lots of surprises in Heaven. (Some will put forward their “mighty works” only to have the Lord say, “I never knew you” [Matthew 7:22-23].)

Virtue is to do God’s will. We are to do God’s will in every part of our lives – in our families, in the workplace, in the church, and in our culture; that is, in our vocations.

The underlying question is, how do we become virtuous; that is, how do we do God’s will? We must know God in order to know His will–which means we must know and trust His Word–and to actually do His will, we need to be saved from our sinful condition through the life-changing work of Jesus Christ. Now we are in the realm of faith. To say that good works are the fruit of faith, which Matthew 7 also teaches in the passage immediately before the one cited above, is a very literal truth. Knowing what Christ has done for us and personally trusting and depending on Him makes us want to do His will.

I totally agree with you when in your book you indicate that coercing someone to do something has no moral value. And when we do something good just to be rewarded, that also compromises the work’s moral value. The politician who shows up at a soup kitchen for 15 minutes while the cameras roll is not necessarily showing virtue, if he feeds the hungry only to boost his image and his polling numbers. The woman who really feels compassion for the homeless and the hungry and so gives up Thanksgiving dinner with her family to serve at the soup kitchen, she is showing virtue and she will have her reward. She is following God’s will and thus is co-operating with God in His love and care for His children. He uses her as His hands and feet, as you say, and He honors that. (Now He may also have used the politician to give food to the hungry during that 15 minutes, and perhaps beyond in drawing attention and building further support for the soup kitchen. The politician himself didn’t do anything particularly virtuous, but God did something good with him anyway, though not by any kind of coercion into virtue.)

God wants us to serve Him and our neighbors because we want to (there is your free agency!) and out of love. And love and good works grow out of faith. ”Without faith it is impossible to please Him” (Hebrews 11:6). The key is “faith working through love” (Galatians 5:6). And this happens in vocation.

WITHERINGTON: I don’t think I have anything to disagree with about this, but I do have a story to tell you briefly.

When we lived in Ashland Ohio, we attended several churches, and I got involved in a very active and excellent Lutheran Church— Trinity Lutheran. In fact, I became a part time cantor at their folk service in the evenings on Sunday. I loved it.

There was just one problem— I couldn’t say the line in the creed about even as Christians we are still ‘simul justus et peccator’ we are still in the bondage of sin. Nope, my that made my Wesleyan and charismatic blood boil. I just went silent when that line of the creed or confession came up. And here is the relevance of this to our discussion – I don’t believe we are still sinners who are called or enabled to occasionally do saintly things. I believe we are set apart by God and sanctified so that we have been freed from the bondage to sin. This is why Paul calls us ‘holy ones’ and any time we do anything that is good and true and beautiful and godly, whether it’s part of our profession or not, it is part of our calling, part of our living out our one true vocation – to be like Christ. I don’t think we have a vocation or calling to be anything else, though God may call us to do a million things. They simply put are not our callings or vocations; they are the good works we have been created in Christ Jesus to do.

VEITH: Isn’t that something, Ben, that you used to go to a Lutheran church! I’m puzzled, though, that you had to confess a creed that referred in any way to ‘simul justus et peccator.’ I can’t think of any creed used in any Lutheran worship service that says that! It’s not in the Apostle’s, Nicean, or Athanasian creeds. Sometimes part of the Catechism is recited on informal occasions, but that’s not in there, as such, and even that isn’t in the liturgy of the Divine Service. Was your pastor just making up creeds for the congregation to recite? He’s not supposed to do that! The liturgy is where we are universal and “catholic”! We belonged to a Lutheran congregation once whose pastor did that sort of thing. We didn’t like it when he made up the liturgy, but we held in there until he started making up the creed. That was too much, so we left.

VEITH: Isn’t that something, Ben, that you used to go to a Lutheran church! I’m puzzled, though, that you had to confess a creed that referred in any way to ‘simul justus et peccator.’ I can’t think of any creed used in any Lutheran worship service that says that! It’s not in the Apostle’s, Nicean, or Athanasian creeds. Sometimes part of the Catechism is recited on informal occasions, but that’s not in there, as such, and even that isn’t in the liturgy of the Divine Service. Was your pastor just making up creeds for the congregation to recite? He’s not supposed to do that! The liturgy is where we are universal and “catholic”! We belonged to a Lutheran congregation once whose pastor did that sort of thing. We didn’t like it when he made up the liturgy, but we held in there until he started making up the creed. That was too much, so we left.

But, of course, that slogan is what Lutherans believe. I do think I am a sinner. I am also a saint because Christ has given me His holiness. We don’t believe in the Wesleyan idea that we can attain perfection in this life. We do have a different understanding of sanctification. We see it as a constant struggle between our “Old Adam” and the new life that Christ has given us, so that we are always coming before God in repentance and coming to the Gospel again and again. And in that process, we grow in our faith and so grow in our righteousness and our holiness. We believe that good works are done in vocation and that the struggles of our ordinary callings are where sanctification happens. But I do agree with this beautiful sentence that you write: ”Any time we do anything that is good and true and beautiful and godly, whether it’s part of our profession or not, it is part of our calling, part of our living out our one true vocation— to be like Christ.”

I don’t want to minimize our theological differences, even though I argue that we agree with each other on more things than we might realize. What I am coming to understand through your book and our discussions is that the different theologies and theological traditions that we have as Christians are going to manifest themselves in their theologies of work.

- Lutheran theology emphasizes God’s action in our lives and His presence in physical means, so that carries over into vocation.

- Wesleyan theology emphasizes human agency, freedom, and the role of good works, so that carries over into a Wesleyan view of work and vocation.

- Calvinists, I have noticed, tend to look at vocation in terms of their understanding of the Third Use of the Law.

- I suspect that Pentecostalists, Anabaptists, and regular Baptists would have their own spin on the topic.

This is understandable and the nature of having particular theologies. What all can agree on, though, is that ordinary human work has a spiritual significance that we need to recover and to live out.

WITHERINGTON: It was part of the confession rather than the creed, we made every single service, and embedded in the liturgy. It’s the I’m fallen and I can’t get up part of the liturgy ![]()

I think this is an excellent insight of yours that theological differences in general will manifest themselves in particular in one’s theology of work. Of course this is especially clear with something like ‘the Puritan work ethic’ but it would be true in all theologies I imagine. For example, in the Wesleyan tradition good works are part of our working out our salvation so it does indeed have to do with our sanctification. We don’t believe in the imputed righteousness of Christ substituting for our actual righteousness. We believe in the imparted righteousness that comes through the Holy Spirit, and that absolutely affects the way we view both work, and good works, and final salvation which is not just a matter of justification by grace through faith.