BEN: One of the topics broached at length in this study is the issue of syncretism. In fact a good deal of what you say reminds me of the interesting study by Ramsay McMullen, one of his last books entitled The Second Church, where, instead of going with the ‘multiple Christianities’ model of Ehrman, he argues instead, and I think rightly for a two levels sort of early Christianity– at the lay level there was considerable syncretism, especially as seen in the funerary practices of ordinary Christians which he documents very well (see also 1 Cor. 15 and the baptism for the dead). At the level of the leadership, and the praxis that went on in the ‘first church’ and well before Constantine, we find a much less broad spectrum of belief and praxis like unto the orthodoxy and orthopraxy advocated by the writers of the NT (as distinguished from say, the Judaizers, the libertines, the syncretists). The voices of the NT do not represent the full spectrum in the early church, but they do represent the official voice, the voice that prevailed even long before Nicaea, while ordinary Christians continued to wear their amulets, worry about untoward spirits and the like. What do you think of this argument, and have you interacted somewhere with McMullen’s case?

BRUCE:

Funny you should mention MacMullen. I have an article coming out later this year entitled “Mark’s Gospel for the Second Church of the Late First Century.” Obviously, for that article I have adopted a strong dose of MacMullen’s argument (although I’m not quite convinced that we can accurately designate “the second church” of the second through fourth centuries as comprising 95% of Christians, as MacMullen does).

The differentiation between what you call “the lay level” and “the leadership” does seem to have been a reality, not only in the years 200-400 that MacMullen outlines, but even in the first century, when there are plenty of indicators that “the second church” was alive and well. It was to “the second church” that “the apostolic voice” (as I like to call it) was frequently addressed – the “apostolic voice” that we hear in the texts of the New Testament and beyond (although even there, the voice was expressed within a spectrum of some diversity).

My essay suggests that Mark’s Gospel fits perfectly into this scenario, as the much-needed “apostolic voice” that sought to correct “the second church” of the late first century. It is easy to interpret the first half of Mark’s Gospel as tapping into the desire for spiritual power and protection of the “second church” but then, in the second half, harnessing that desire in relation to an exclusive devotion to Jesus Christ and a cruciform pattern of discipleship.

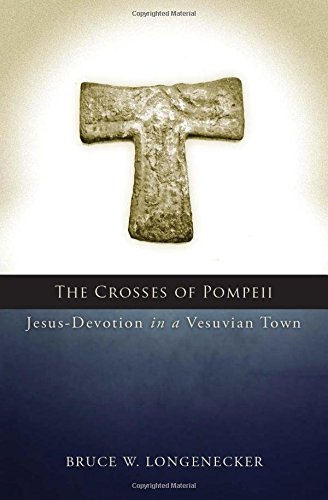

It was when the Pompeii pieces of first-century Jesus-devotion fell into place that I came to a new appreciation of Mark’s Gospel. The old adage that Mark’s Gospel links a “theology of glory” to a “theology of the cross” (with a variety of scholarly variations on that theme) came alive with new urgency, in light of what I was finding about Jesus-devotion in Pompeii, where Jesus-devotion seems intricately tied to strategies of protection in a dangerous world. Against this backdrop, Mark’s Gospel is not simply an interesting theological contribution to Christian discourse but is an urgent corrective to the “second church” of the first century – the sort of thing that we might be seeing in Pompeii, and if in Pompeii, no doubt elsewhere as well. (Of course, Mark’s Gospel may well have been doing other things as well, but if it was a text written “for all Christians” [to use Richard Bauckham’s term], the Pompeian data opens up one vista in which see one application of its potential impact in its original setting.)

BEN: Your discussion of the Hebrew +, or Taw, the last letter of the Hebrew alphabet used on ossuaries and elsewhere to signify God’s property and the devotion of the person in question is fascinating. (It of course flatly contradicts the Talpiot tomb folks who think that the + symbol must indicate a Christian tomb, even a tomb of Jesus himself, with bones intact.) I wrote you an email asking if you had considered not only the connection between Ezekiel’s mark on the saints and the + and the reference in Rev. 7, but also the possibility that John in Revelation envisions not the + or Taw but the Omega or even Alpha and Omega mark as the one the saints bear (since the alpha and omega is predicated of both the Father and the Son in Revelation). This would contrast quite nicely with the mark of the beast on the Emperor worshippers. What do you think?

BRUCE:

I’m not sure about your idea in particular, but then again, nothing would surprise me in this regard. The first-century world of religious symbolism was extremely rich. Jews and Christians frequently probed deeply into symbolism that they found embedded within Jewish scripture and tradition.

And the more you dig around in the ancient world, the more you recognize that what seems extraordinary to us was not out of the ordinary for people of the past. Some ancient people appreciated theological connections of the most subtle and intricate kinds. I tried to demonstrate this in relation to Luke’s Gospel in my little book, Hearing the Silence, which argues that the Lukan evangelist expected his audience to explore subtle theological connections – both intratextual connections within his narrative and intertextual connections beyond it (especially with reference to Psalm 91).

But pride of place in this regard is the book of Revelation. I often think that anyone interested in exploring the religious imagination of a first-century creative mind needs to start by reading through Richard Bauckham’s book The Climax of Prophecy. It is a fascinating study of that text, demonstrating just how creatively

agile an ancient mind could be in terms of making theological connections between resources within the Judeo-Christian tradition.