By historical Adam and Eve I simply mean real people in space and time, the progenitors of God’s people who were the sinners in question that set in motion the train of murder and death and iniquity that followed, no sooner than they stepped outside the garden (see the story of Cain and Abel). I do not think it is adequate to suggest that the writers of the NT or for that matter of the intertestamental period were simply referring to Adam and Eve as archetypal or literary figures in a story.

No, they believed these folks actually existed on planet earth long long ago. Indeed, so much did they take that for granted, that they argued from that basis to be able to say other things about Adam and Eve. I find weird the argument of John Walton cited on p. 109 that says because Christ is called the last Adam, since he was not the last biological specimen, one cannot conclude that when Paul refers to the first Adam he means the first biological specimen. Paul is talking about two founders of the race of God’s people— the first one, who is the progenitor of God’s people and the last one who will also be the progenitor of God’s people. Biology is neither implied nor denied by this rhetorical comparison, for either Adam.

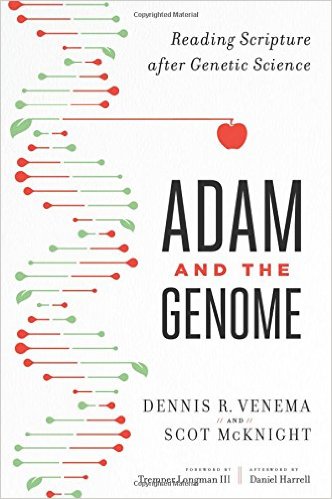

The chapter about the Twelve major theses, which begins on p. 111 makes up the bulk of Scot’s main argument. It begins with a very ironic quote from Walter Brueggemann on p. 112. Speaking about the theologians who wrote Gen. 1-11 he says of them “they resist a scientific view of creation which assumes the world contains its own mysteries and can be understood in terms of itself without any transcendent referent.” Indeed— it’s a pity that the first half of this book didn’t approach the matter more like the writers of Gen. 1-11. This quote accurately describes what we find in this book in the discussion on genetics.