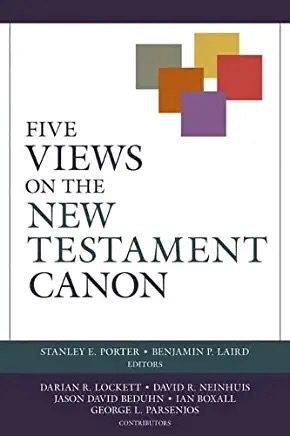

Five Views on the New Testament Canon, eds. S.E. Porter and B.P. Laird, (Grand Rapids, Kregel, 2022), 288 pages, $24.99.

In recent years there have been a slew of books with four or five views on some topic important to students of the Bible. This is another one, and interestingly it involves Protestants Catholics, and Orthodox scholars sharing and comparing their views on the complex manner of NT canon formation. Three of the views are by Protestants, or at least by people well conversant with the Protestant views on such matters (and two are labeled some sort of Evangelical, the other representing liberal Protestantism). Doubtless this is because the folks putting this together know that the main audience for such books by Kregel are Protestants, and chiefly Evangelicals. But it is very helpful that both a Catholic and an Orthodox scholar are allowed to weigh in on the matter, and critique the other presenters as well.

No book can be all things to all people, and this is a good book remarkably free of unnecessary and unhelpful polemics. It involves respectful dialogue, but if you are looking for a deep discussion of what counts as truth, what counts as the Word of God, what we should think about the relation of history to theology, and particularly what we should think about the inspiration of Biblical texts, there is not a surfeit of discussion on those relevant topics, though there is some. For instance, there is little or no discussion about how sacred texts worked and were viewed in an overwhelmingly oral environment in early Judaism or the Greco-Roman world. There is no real discussion about whether inspiration somehow produces truthful discussions about history, theology and ethics in the NT. There is also next to no discussion about the relationship between the closing of the canon of the OT and the canon of the NT even though all the quotations of the OT in the NT with one possible exception (Jude quoting 1 Enoch, but he does not quote it as ‘Scripture’ but as a true prophetic utterance) all come from the 39 books of the OT that all Christians and also Jews recognize as Scripture. This suggests that the OT canon was de facto closed by the time the NT documents were written, and provided Scriptural resources for the composers of NT documents, all of whom or almost all of whom were Jews. What we do get in this volume is elongated discussions and debates about whether the church authorized and canonized the NT books, or merely recognized them as authoritative on the basis of certain criteria— apostolicity (in some sense), catholicity, widespread use etc. What about the criteria of veracity of content?

There are many positive things to say about this volume, and here are some of the things: 1) it makes very clear that all the participants recognize that the NT is (and I would add, should be) these 27 books plus nothing. Other early Christian literature is valuable but not canonical, not NT Scriptures. 2) Protestants Catholics, and the Orthodox have more disagreements about what the OT canon includes than the NT canon. Only Protestants are in agreement with Jews about the extent of the OT canon; 3) the term kanon itself refers in the first instance to a measuring rod, and came to refer to canonical limits of the NT, something that no sort of definitive statement was made about before the 4th century. And as Prof. Boxall says, the real watershed moment for Catholics was at the Council of Trent (on which see below). 4) Note the helpful definition of apostolicity by Prof. Boxall on p. 143: “Apostolicity is understood rather as the preservation of the original apostolic response to the Christ event, first conveyed through the preached Gospel, and preserved both orally in the ongoing transmission of the apostolic tradition, and in written form in the writings now recognized as canonical. The authority of the NT writings lies in their preservation of the authoritative testimony from ‘the closing period of foundational revelation.’” Note the reference to revelation. The NT is not viewed as mere human words about God, but as revelation. What should have been also said in this statement is that the authoritative testimony is a true testimony. Its authority doesn’t primarily lie in which human being said it, but in what was said when the truth was revealed. 5) Prof. Boxall rightly stresses that at the heart of all these texts is a person— Jesus Christ, a living person, indeed the risen Lord, not merely a collection of texts. But does this mean that the teaching of Jesus is somehow more inspired than say the teaching of Paul? The early church fathers do not in the main seem to think so. Here, I’m thinking particularly of people like John Chrysostom.

Something has to be said about the false notion that shows up in places in this volume that the writers of the NT had no clue they were speaking or writing God’s Word, but rather that idea was a clearly ex post facto judgment. Just for a moment let’s talk about probably the earliest contributor to the NT— the apostle Paul. Consider for a minute what’s in perhaps our earliest NT document—1 Thessalonians 2.13— “And we also thank God continually because, when you received the word of God, which you heard from us, you accepted it not as a human word, but as it actually is, the Word of God, which is indeed at work in you who believe.” Paul of course is talking about hearing the Good News about Jesus which he calls ‘the Word of God’, and he quite clearly says it was properly received as not merely the words of human beings, but THE WORD OF GOD. In fact, he says that it is actually the Word of God, the change agent at work in those who believe. In fact, the phrase ‘logos tou theou’ throughout the NT, when it does not refer to Christ himself (e.g. in John 1) refers to the oral proclamation of the Good News and the truth about Christ. This is true where this phrase occurs in Acts and also in Hebrews where that word of God is said to pierce to the depths of a person’s being and changes that person. Paul, and others believed they were inspired to proclaim God’s Word that told the truth about Jesus (see my The Living Word of God, on this and on the issue of whether the canon misfired or not!). It’s not enough to talk about canon consciousness. We need to discuss Word of God consciousness spoken of above, Scripture consciousness (see 2 Pet.3—- “He writes the same way in all his letters….which ignorant and unstable people distort, as they do the other Scriptures”), and yes canon consciousness. Both Word of God and Scripture consciousness already existed and was applied to what is now the content of the NT, including the earliest Pauline content, long before the canon or canon consciousness appeared in early church history. The failure to deal with the historical situation of genuine Christians before there was a canon of Scripture and yet for whom various of these texts were soul nourishing and coming from God through human writers is a significant failure in some forms of canonical criticism.

Now we can debate what the relationship of this oral proclamation is to written words, but when we actually look closely at a text like 1 Cor. 7, Paul stacks up his own pronouncements alongside of Jesus’ in regard to divorce, and thinks they have the same authority for his audience as Jesus’s words. And if there was any doubt about that he tells them that he too, like Jesus, has the Spirit of God inspiring his words. I do not personally doubt Paul believed his written words were viewed by him as just as authoritative as his proclaimed words. Indeed, his letters contain what he would have proclaimed orally to various congregations had he been present there. They are oral and rhetorical discourses. Put another way, they are the preaching of God’s Word in written form.

And are we really to suppose that when we read in regard to the OT Scripture that it is God-breathed that somehow the writer thought that the content of the writers of the NT about Jesus as the Savior of the world were somehow less authoritative or truth-telling than the God-breathed OT? The answer is surely no. They did not. They believed God’s inspiration applied not just to speaking but also to writing, just as was the case with the OT prophets like a Jeremiah. The authority of what was said was determined by the truth of the content itself as inspired by God. A secondary thing that gave authority to what was said is who it came from—- from eyewitnesses (cf. Lk. 1.1-4), from apostles, and from the co-workers of both apostles and eyewitnesses. And since that, broadly speaking, became the criteria used to determine what books should be consider inspired NT texts in due course, then automatically any documents created after the apostolic period of whatever sort were ruled out as canonical Scriptures of the NT.

Of course, it is true that various Christian writers of the 2nd through 4th century were not always clear on the criteria for what counted as their new Scriptures, but happily various parts of the church recognized these 27 documents as their NT in the fourth century. No canon lists or codexes included any Gnostic documents, or the Gospel of Thomas, or the Acts of Paul and Thecla, or other second century documents though there was some debate about the Gospel of Peter and the Shepherd of Hermas early on and occasionally such a document showed up in a codex, but it may be debated whether we should view codexes as canon lists. More likely they are approved Christian reading lists.[1] And even the Gospel of Peter, when read by a church authority was disapproved for reading in church.

One of the lacuna of this volume is any detailed discussion of the importance of text criticism, of establishing the earliest Greek text of the NT as best we can. Thankful the editors of the volume in their conclusions have a brief discussion of the matter and offer a helpful listing of volumes where we can track down the canon lists and other helpful resources. This is good, but contrast this with statements about the Council of Trent that Prof. Boxall rightly draws our attention to. There is a huge problem with the Council of Trent’s pronouncement about the 27 books of the NT because they added the phrase ‘in all its parts”, which includes the long ending of Mark, John. 7.53-8.11 and the additions to Luke’s passion narrative.[2]

This is problematic on several counts: 1) text determines canon in regard to this matter. By this I mean that no clearly later additions to the text in the second or later centuries should be considered the original inspired text of NT Scripture. This is just a basic principle of text criticism widely recognized today, and is rightly the basis of the revisions of NT translations in the last century; 2) of course when the Council of Trent made its decision in 1546, Latin was still the official language of the Scripture and liturgy of the Catholic Church, and proper text criticism didn’t truly exist, even to the point of not giving priority to the original language texts of Scripture. Latin was in any case the original language of no NT text.[3]

When one considers the intertwined nature of history, theology, and ethics in the NT, and especially in the Gospels and Acts the question that has to be raised is this— If the text is making both a historical and a theological claim, how should this be viewed? Can a text be both theologically true and historically false? My answer to that question is no, if the theology in question is grounded in and dependent on some historical occurrence. So, for example, as Paul makes clear in regard to the resurrection of Christ in 1 Cor. 15— if Christ is not raised then his death atoned for nothing and we are still in our sins. History and theology are intertwined because early Christianity is a religion grounded in, and based on some historical claims, especially about Jesus. It would have been good if one of the writers of these chapters was an ancient historian who had actually written a book on NT History.

The NT is full of theologizing which needs to be interpreted, and it does not require a later ‘theological or canonical reading’ of the text to make it theologically important or significant. Later theological readings of the text are fine, if they comport with or are a reasonable exposition or amplification of the theology in the Scriptural text itself. The fact that the original texts of the NT are words on target for those first audiences does not mean they could not be words on target for other and later audiences as well. But the important point is that what the text meant in its original setting is still today what the text means— hence the need for good detailed contextual exegesis. It may have a different significance or application today, but what it doesn’t have is a different meaning. Meaning is in the configuration of the words in the Greek text, not in the eyes of the beholder, even though it is true we are all active and even creative readers of the text. What must be guarded against in such readings is reading something into the text which does not comport with the actual meaning of the text. In other words, the sin of anachronism needs to be avoided.

In the first couple of chapters by Evangelical scholars, the chapter by D. Lockett is far less problematic than the one by D. Nienhuis. The latter follows the sort of canonical approach to the Scriptures we find in the work of Robert Wall and others. While I have no problem with the notion that the NT once assembled in a particular order took on further significance, provided further insights, led to new applications of the NT, there is however a big problem with seeing this as the point at which we find the definitive meaning of the text or the point at which it became Scripture for the church. It had already been Scripture read in church for generations before then. A text without a context is just a pretext for whatever you want it to mean and the original contexts of each of the NT documents is the first century audiences to whom it was sent.

It was the Word of God for those earliest Christians first, before there ever was a collection of Gospels, or Paul’s letters or the Catholic epistles, and since it is the same texts with the same words which later became part of the NT canon its meaning did not suddenly show up in the fourth century A.D., nor for that matter its original significance. The sort of canonical criticism suggested in Nienhuis is largely a-historical or to some degree anti-historical in approach (or later 4th century historical in approach). It somehow mistakes liberal and radical historical criticism of the NT as either the only sort of critical historical study there is of these texts, or suggests we must simply accept the notion that there are pseudepigrapha (see p. 90) in the NT canon, a suggestion many and perhaps most conservative Protestant and Catholic and Orthodox scholars would rightly reject. As Richard Bauckham and others have made clear, there was a serious problem with pseudepigrapha when it came to the truth claims within a document. As Bart Ehrman demonstrated at length— such documents are forgeries, and there is clear evidence from the second century and later that church leaders rejected such documents as not to be read in church, much less later included in a NT canon.[2] The Pastoral Epistles, for example, were not viewed as such by the early church.

Underlying all the discussions in this volume is the issue of the relationship of Scripture to later church tradition, with various authors suggesting that these are two streams of Christian teaching worth studying and learning from, which is of course true, with some suggesting that the tradition outside the NT canon is in various ways as authoritative as the tradition inside the NT canon. I prefer the statement of my old Princeton Teacher, Bruce Metzger that the church recognized what the Holy Spirit had guided the church to see as its NT Scripture, it did not determine the canon. As such the canon of the NT was to be seen as the norm of all norms which can be supplemented by, amplified by, explained by other traditions, but can’t be supplanted by, corrected by later traditions. Only the NT documents are revelation from God, not the later traditions that can supplement and explain such revelation.[4]

Prof. Parsenios says that the Orthodox tradition never felt it necessary to make a definitive statement about the limits of the NT canon, unlike the Council of Trent. This is perhaps in part because the Protestant movement was born in Europe out of Roman Catholicism, not out of the Orthodox tradition, and the Council of Trent was of course part of the attempt by the Catholic church to counter the Protestant Reformation. Happily, this volume helpfully proves we don’t need to be anathematizing each other anymore. Rather, we can have respectful dialogue, even with significant disagreements and can actually work towards understanding canonical matters better together as brothers and sisters in Christ.

It is the measure of a good book like this one that it teases the mind into activity thought as C.H. Dodd used to say about Jesus’ parables, and produces vigorous and hopefully helpful responses. I highly recommend this book for that very reason, however much I may disagree with this or that point of the five main contributing writers.

[1] On the issue of the Muratorian fragment being a second century canon list, see not only the article by J. Verheyden listed in the Five Views book in a note on p.47, but also my deconstruction of the later date theory by Hahneman in my, What’s in the Word? (Baylor U. Press, 2009).

[2]. See Ehrman, Forged: Writing in the Name of God, (Oxford, 2012).

[3] The council went on for many years, starting in 1545.

[4] See my lengthy discussion of this issue in Letters and Homilies for Hellenized Christians, Vol. One. (IV Press, 2014).