A lot has changed with witchcraft, both socially and individually. Historic witchcraft may, in fact, be sufficiently removed from its modern counterpart as to be unrecognisable in a time when there has never been more positive media exposure as with the rise of the aesthetic, social and lifestyle witchcrafts which affirm individuality and “…empower us to grow, change and heal.”[1]

There are some common and easily identified mistakes with this vogue understanding of witchcraft, which is little helped by some quarters of Traditional Witchcraft, who see the label as a license to cherry-pick in the name of eclecticism, and also some public faces of Wicca, who fail to look past there own nose and definitions/opinions. In addition, those few traditions, from both ends of the spectrum, which have survived from the middle of the last century have been seen to assume a position of provenance over the rest of us as to be quite supercilious and, therefore, removed from the greater community. This little post is likely to be contentious to some in either camp, for which I make no apology.

Many years ago, the internet was a steam powered tractor unit that required a delicate and rehearsed ritual in order to engage it, demanding patience and hard work as the screeching wail emitted from the idol heralded the evocation to physical manifestation of a screen image, appearing before you pixelated line by pixelated line. It was a simpler time, when a myriad of cables and plugs abounded and command of such wire trickery bestowed upon the user the magisterial title of ‘web master’. Meanwhile, in another room, with a separate interface, there were those wizards amongst us who were adept at surfing the web, like a keyboard hunter with the dexterity to type with more than a single digit and fire out code and sentences in the blink of an eye. Those of us who had dedicated our time to the diligent scouring of the first incarnation of the internet were able to perform feats that would now be curtailed by the algorithms, privacy policies and incessant need to harvest user data to target advertising, thereby crippling exploratory uses of the search engine and limiting it only to those things that the now mature internet deems worthy of your puny mortal brain.

Back in those heady days, before vastly more powerful internet computers were placed in all of our pockets, along with all of the music ever, I stumbled across an anonymous webpage that fascinated and imprinted its simple message upon me. It was a glamorous affair for those days, mostly black with some crude pixels, the odd banner ad no doubt enabling the ownership of the web address for free. It was mostly text and precious little of that. In tone, it was quite critical of modern renditions of witchcraft, perhaps rose-tinted memory masks a downright scathing timbre within the stark message. However, one thing stuck in my mind to this day. It simply stated: if you want to do real witchcraft, first learn to get out of your body, with the caveat to not be alarmed or afraid if, in doing so, an actual disincarnate witch turns up in the dead of night wondering why you called.

The point of this is to illustrate one of the most basic and fundamental things which was once a staple in the esoteric and occult worlds, with magic orders and organisations teaching astral vision, use of the etheric double, energy work and such like. I’m sure you’re thinking, this all sounds far removed from the historic witch. Isobel Gowdie was hardly crouching in her dank, infested mud hovel practicing the Middle Pillar Exercise, or awakening her chakras as she scrabbled around in the dirt for any root which might contain sufficient calorific value to justify another breath. Clearly, these people had more things on their minds. Didn’t they?

As a former student of Medieval History at the University of Wales, one of the most important things I have taken away, and which was instilled from some of the first lectures, is that we cannot (indeed must not) view a culture separated from us by time and distance from a place of morality and current mores. That is to say, we may not measure the ethics, politics, social makeup or traditions of peoples living in the past, or another culture entirely, using our own worldview as a measure. This is one of those lessons that may be applied in life to a good many circumstances and is not limited to history but necessary in sociology as a whole. We may not judge another’s culture or tradition as morally incorrect because we do not partake of it, nor can we wholly understand it from the outside alone.

Habitus: is a system of embodied dispositions, tendencies that organise the ways in which individuals perceive the world around them and react to it. These dispositions are usually shared by people with similar background, as the habitus is acquired through mimesis [2].

The habitus which was shared by the individuals of 17th Century self-confessed witch Isobel Gowdie suggests a worldview that was in close proximity to the deceased, which in itself is sufficient relationship with the ‘other’ or ‘unseen’ to equate perfectly with a fairy belief and witchcraft (Lecouteux, 1992). Death was a constant companion to Gowdie and her contemporaries, haunting the very landscape in which she lived and was as close as the wind on the cheek. Indeed, academics have postulated that the supernatural phenomenon reported in this period all indicates a relationship with death, the veil between the two worlds being so thin as to be, on ocassion, unrecognisable (Wilby, 2005). Through this, we have those cunning folk and witches, such as Bessie Dunlop, who report meeting with a familiar spirit, or fairy, being the image and apparent personality of the deceased[3].

Claude Lecouteux, professor of medieval literature and civilisation at the Sorbonne, emphasises this relationship with the dead as the ‘otherworld’ itself, together with the medieval notion of the ‘double’ as an aspect of the makeup of the soul. Through the evidence of the reports of witches, werewolves and fairies (coincidentally the title of one of his books), Lecouteux, along with Wilby, identifies the otherworld as a place of the dead, fairies and associated spirits. It is suggested that the successful magician or witch can externalise, or else work the imagination upon, the double and may similarly impact upon the double or unseen aspect of another. These individuals were capable, spontaneously or intentionally, of leaving the physical body, now in a state of catalepsy, and travel as the ‘double’, even transforming into the shapes of other creatures. Various reports of witches assuming animal form and receiving injury whilst in this shape, and which later appeared on the entranced body, are suggestive of the link between the double and the physical. Accounts of the infamous Witches’ Sabbath, then, are almost certainly experiences of a congregation occurring whilst travelling in the double.

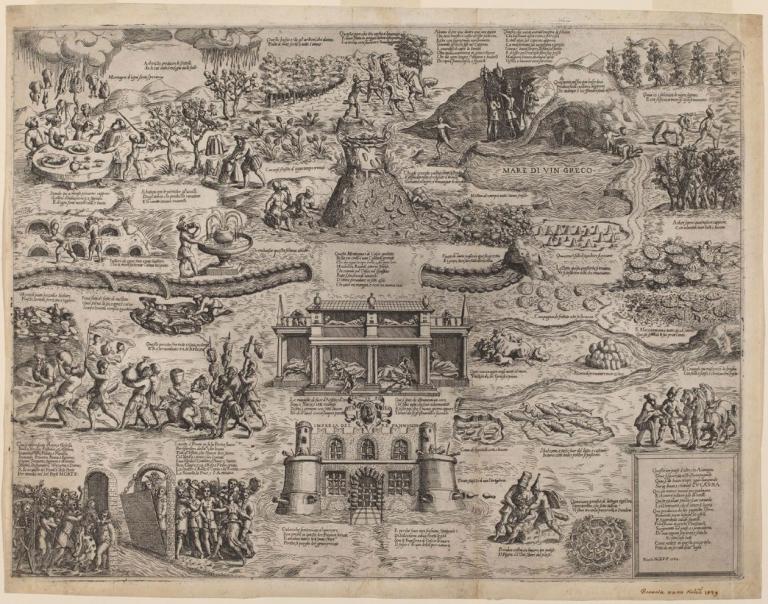

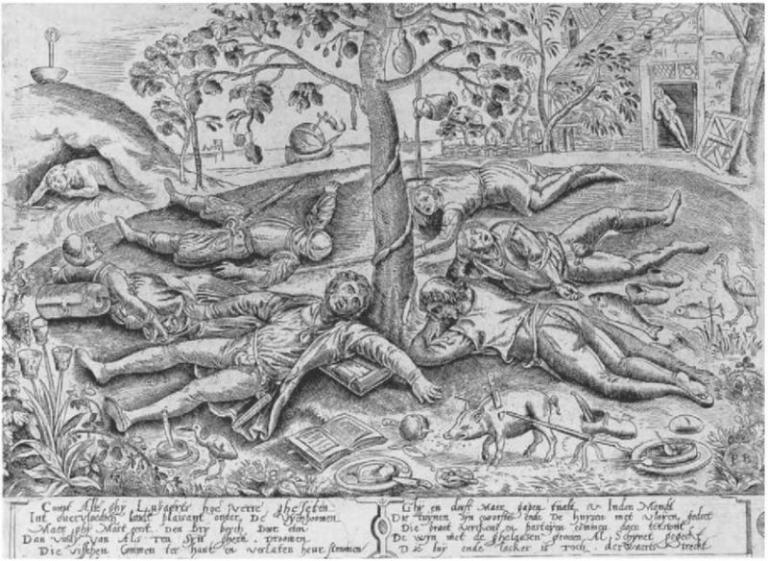

Furthermore, oneiric vision and otherworld work is regarded as working upon the same or related planes, while the depth of altered states of consciousness occurred with a frequency and tendency that would be unprecedented in our own reality. Consider the constant of hunger, the daily struggle to obtain sustenance, tiredness and fatigue which would accompany such a lifestyle in abject poverty, as well as the proximity of illness and disease that poor sanitation and hygiene brings, we can perhaps understand the proclivity to engage with the world of ‘other’ and the spirits of the deceased in the realm of the imagination. Indeed, we can evidence such a tendency in the literature, tradition and folklore of utopian ‘otherworlds’ wherein all was a reverse of the reality of the physical. One such is the medieval tradition of the Land of Cockaigne, a mystical utopian reality, a world of plenty where there is an abundance of food and drink, sexual liberty, all social rules are turned on their head. Such a world would appeal greatly to the Gowdies and Dunlops who fortune treated so poorly. Another incidence of the otherworld is the land of faery itself, where the night train of the dead and unseen spirits revel in a topsy turvy world, described as being the opposite of the mundane world in that night is day, winter is summer, etc.

So different are the worlds of the historic witch to that of the modern counterpart, separated not only by time but by realities, existing in more than different times but utterly alien realms. Furthermore, our understanding of the historic place of witchcraft in our modern mind has altered completely within the bounds of our shifting social environment. No longer is the divide between the physical and unseen a thin veneer, nor the ‘other’ perceived as removed from the harsh realities of life. The new lifestyle identity witchcraft is developing exponentially, with YouTube channels, Instagram pages, and even cosmetic purveyors Sephora getting in on the trend with its $42 ‘Starter Witch Kit‘, whatever the hell that is!

[1] Witchcraft: A Beginners Guide to Witchcraft, Sophie Cornish 2015. This is an introduction to witchcraft, used interchangeably in the description with ‘wicca’ and identified as being “based in the spirituality of our ancestors who worshipped the Goddess, God and natural universe,” which historic late medieval, early modern witches almost certainly never did.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Habitus_(sociology)

[3] Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits, Emma Wilby

[4] Witches, Werewolves and Fairies: Shapeshifters and Astral Doubles in the Middle Ages, Claude Lecouteux (Fr. 1995, En. 2003)