Sunday marked the 15th anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon. Many of us can likely remember where we were that morning. And even as many of us will never forget the trauma of that day, this anniversary is an opportunity to reflect on what the passing of fifteen years means in our cultural memory.

As difficult as it is to comprehend, part of what the passage of time means is that “nearly one-fifth of the current population was born after the attacks…and a quarter of Americans were too young to have any significant or meaningful memory of the day.” All of the eighteen-year-old freshmen entering college this fall were three-years-old on September 11, 2001.

This anniversary year also means reflecting on the continuing impact of our response to the attacks. As devastating as the attacks were — almost 3,000 people killed and more than 6,000 injured — our collective responses has also had a tremendous toll. Yes, we had to respond. But according to the Costs of War Project at Brown University, which has tracked the costs of the post-9/11 wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan:

- Over 370,000 people have died due to direct war violence, and many more indirectly

- 210,000 civilians have been killed

- 7.6 million war refugees and displaced persons

- The U.S. federal price tag for the Iraq war is about 4.8 trillion dollars

- The wars have been accompanied by violations of human rights and civil liberties, in the U.S. and abroad

- The wars did not result in inclusive, transparent, and democratic governments in Iraq or Afghanistan

There have been many important books written about both the 9/11 attacks and the impacts of our response, and there are

many significant angles to consider. But in the limited space of this post, I would like to reflect on the ways that a culture of toxic masculinity is one among many factors that both precipitated the attacks and triggered some of the most damaging aspects of our response.

many significant angles to consider. But in the limited space of this post, I would like to reflect on the ways that a culture of toxic masculinity is one among many factors that both precipitated the attacks and triggered some of the most damaging aspects of our response.

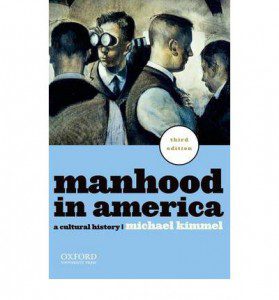

This post draws on the sociologist Michael Kimmel’s book Manhood in America: A Cultural History, 3rd Edition (Oxford University Press, 2011). I should also add here at the beginning that, as I explored a few weeks ago in a post on “Gender Liberation,” the term masculinity does not necessarily correspond to biological anatomy. Instead, different ones of us find ourselves at different points on that masculine-feminine continuum at different points of our lives.

To say more about the term “toxic masculinity,” I am referring to the stereotype of cowboy swagger: that if a so-called “real man” is attacked, then he will respond with a violent, unemotional, strike-first-and-ask-questions-later aggression in order to reestablish dominance and control. And looking back on the history of this country, historians have described our primary model of masculinity as the “self-made man” (ix). One of the problems with this model is that it creates a perpetual anxiety around proving one’s manhood. If one’s self-worth is produced through being a self-made man, then any failure brings one’s manhood into question — and must be avoided at all costs.

Consider this observations from a sociologist:

In an important sense there is only one complete unblushing male in America: a young, married, white, urban, northern, heterosexual, Protestant, father, college educated, fully employed, of good complexion, weight, and height, and a recent record in sport…. Any male who fails to qualify in any one of these ways is likely to view himself — during moments at least — as unworthy, incomplete and inferior. (4)

I invite you to pause and consider the masculine-identified people in your life and the ways they relate to the anxiety of constantly trying to prove themselves in all those arenas. More broadly, with changes to our economy due to globalization and other factors, increasing numbers of men have experienced themselves slipping farther and farther away from this ideal of the self-made man. Moreover, at the same time, many of these ideals have been called into question by the women’s movement, the Civil Rights Movement, the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Rights movement, and more.

The pressure to be a self-made man means that immigrants and women competing in the workforce can be experienced as an existential threat to one’s manhood (217-218). (There are many examples of this dynamic in the news in recent months.) Ironically, the result is men, who are supposed to be so “rational” compared to the supposedly more emotional women, are increasingly moving from anxiety to anger and even rage (ix). But men are no less emotional than women, we are often just more culturally conditioned to repress our emotions — and when those repressed emotions are released, it can be explosive. And in recent decades we have seen an exaggerated backlash of “unapologetically ‘politically incorrect’ magazines, radio hosts, television shows,” and political movements (239-240).

One of the most telling complaints is a white man angrily lamenting that some “other” (immigrant/minority/woman) stole my job. Can you hear the entitlement in that complaint (244)? I do not know of any gentler way to put it than that straight white men have become so accustomed to racism, sexism, and homophobia giving them unfair advantages that, “equality feels like oppression.” But “loss of privilege is not the same as reverse discrimination.”

To look deeper beneath the surface, allow me to share one of the biggest insights I have found from the field sometimes know as “men’s studies” or “masculinities studies.” Contrary to conventional wisdom, masculinity is much less about “the drive for power, domination, and control” and much more about the fear of being dominated by others or others having power and control:

Throughout American history, American men have been afraid that others will see us as less than manly, as weak, timid, frightened. And men have been afraid of not measuring up to some vaguely defined notions of what it means to be a man, afraid of failure. (5)

It turns out that, “American men define their masculinity, not as much in relation to women, but in relation to each other” (5). The real fear is of “being ashamed or humiliated in front of other men” (6). So much toxic masculinity — so much false swagger, unnecessary aggression, and repressed emotion — has resulted from seeking to mask the fear of being ashamed, humiliated, or dominated.

As I quoted in a recent post about Brene Brown, “You might be able to lie, cheat, and steal your way to success, fame, and wealth. But ‘vulnerability is the only path to more love, belonging, and joy.’” And in far too many cases, all that fake cowboy bravado has prevented many men from being honest about their emotions: their fear, shame, anger, sadness — even their joy. The result has been so much unnecessary harm, damage, and expense to self and others — and loss of opportunities for love and belonging.

And although the model of being a self-made man has been particularly dominant in U.S. history, there are many other models of masculinity. One historically dominant model in Europe is finding one’s self-worth in “the life of the community and the qualities of [one’s] character” (14). But due to the influence of the European Enlightenment, by the time of the American Revolution, the paradigm was shifting away from “service to community” and toward “individual achievement.” As a result, the pressure to be a self-made man has been particularly dominant in our country since the beginning. But the shifts in how masculinity has changed over time can give us permission to allow understandings of masculinity to continue evolving in healthier directions.

I’ll briefly name two more of my favorite examples of how much ideals of masculinity have varied over time and in different cultures. First, if you go back to the mid-nineteenth century, muscular men were considered less desirable because muscles indicated that you earned a living as a laborer. Consider these two descriptions from that time:

- “An American exquisite must not measure more than 24 inches round the chest; his face must be pale, thin and long; and he must be spindle-shanked,” meaning lean.

- “There is nothing our women dislike so much as corpulency; weak and refined are synonymous.” (21).

Today the opposite is the case: “men’s interest in health and diet has matched women’s only twice in our history — at the turn of the twentieth century and today.” From one sociological perspective, this shift is directly related to changes in the workplace: “When our real work failed to confirm manhood, we ‘worked out’” (225).

And just as you can study the increasingly perverse beauty standards represented by Barbie dolls, you can also take

G.I. Joe’s proportions and translate them into real-life statistics. In 1974, G.I. Joe was 5 feet 10 inches tall and had a 31-inch waist, a 44-inch chest, and 12-inch biceps. Strong and muscular…but at least within the realm of the possible. By 2002…he’s still 5 feet 10 inches tall, but his waist has shrunk to 28 inches, his chest has expanded to 50 inches, and his biceps are now 22 inches (almost the size of his waist). (247)

Those standards are absurdly unrealistic.

To give one more (among many other possible examples), if you look back less than a century, here’s an excerpt of a 1918 editorial:

there has been a great diversity of opinion on the subject, but the generally accepted rule is pink for the boy and blue for the girl. The reason is that pink, being a more decided and stronger color, is more suitable of the boy; while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl. (Kimmel 117)

Fascinatingly, the reasons the colors switched in ensuing decades is not fully clear. But the upshot is that so much of gender politics has occurred for historically contingent reasons. And the fact that our conceptions of gender have changed so much over time should embolden us that they can continue to be changed in the direction of equality.

This shift is vital for all of us. To quote a passage about men from Betty Friedman’s classic The Feminine Mystique:

How could we ever really know or love each other as long as we kept playing those roles that kept us from knowing or being ourselves? Weren’t men as well as women still locked in lonely isolation, alienation…? Weren’t men dying too young, suppressing fears and tears and their own tenderness? It seemed to me that men weren’t really the enemy — they were fellow victims, suffering from an outmoded masculine mystique that made them feel unnecessarily inadequate when there were no bears to kill. (190)

When I reflect on these gender dynamics, some of the lyrics that come to mind are from Dar Williams’s song “When I Was a Boy.” It’s a lament about moving from the freedom she experienced as a young girl, who loved being a tomboy, to all the restrictions that were imposed on her as others began to increasingly view her body through a gendered lens. No longer could she climb trees, get grass stains, and ride her bike around shirtless. Instead she was told to look pretty, that she could now be arrested for taking her shirt off, and that the world was so dangerous for women that she should “find a nice man to walk her home.”

In the closing stanza of the song, she confesses to her boyfriend, “I have lost and you have won” — meaning that women has lost and men have won. But he surprises her and says:

Oh no, can’t you see

When I was a girl, my mom and I we always talked

And I picked flowers everywhere that I walked.

And I could always cry,

now even when I’m alone I seldom do

And I have lost some kindness

But I was a girl too.

And you were just like me, and I was just like you.

In the coming days and weeks — when conflict inevitably arises — what might it look like to not shut down, but instead to open your heart?

What might it look like to risk being honest about the fullness of who you really are — and the fullness of who others really are?

What might it look like to try taking off the masks that culture tells us we have to wear — and instead to stand on the side of love for others and for yourself?

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a trained spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism: http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles