Today’s guest post is by Kevin M. Johnson, one of the co-hosts of the Encountering Silence Podcast.

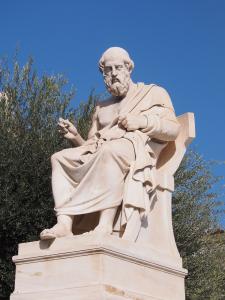

I see, my dear Theaetetus, that Theodorus had a true insight into your nature when he said that you were a philosopher; for wonder is the feeling of a philosopher, and philosophy begins in wonder.— Plato, Theaetetus

Recently, I have publically identified myself as a “recovering academic.”

I have quickly grown fond of using this label. While I love to teach at the university level, parts of the job just do not make sense to me. That is probably a complaint as old as universities themselves — but by gently mocking my status as an academic, I create some humor and distance rather than annoyance. (Think of the old Elvis Costello song: “I used to be disgusted, and now I try to be amused!”)

Another reason I like to call myself a recovering academic, is because I am interested in recovering aspects of teaching and learning that we seem to have forgotten or have become distorted in unhelpful ways.

This “lost aspect” of learning concerns how we come to know anything and how to pursue wisdom for a full and well-lived life. In my work as a theologian, I began to ask more and more what one means by “knowing” in terms of religion and theology. In asking that question, I saw there was a huge difference between the mental map we currently use to comprehend learning and wisdom, and the map philosophers and theologians used in centuries past to describe it.

The difference between these two maps is shaped by silence and contemplation.

Two Ways of Knowing

The current lens we use to examine the world — and the language that accompanies that lens — actually filters out the contemplative way of knowing. In the past, such a way of knowing was assumed and accepted; but as we have lost the contemplative way of knowing, our contemporary filters distort the very foundation of how we learn (and teach) what there is to know.

To illustrate this, let’s look to the foundation of all Western thought and knowledge — the Greek philosopher Plato. Plato reminds us wisdom is saturated in silence. Philosophy, the love of wisdom, begins in wonder, an emotion of contemplation, surprise, and deep attentiveness.

Philosophy — literally, the love of wisdom — originally was seen as a way of life. Philosophers focused on practices to discover wisdom and how people could engage in those practices to open themselves up to wisdom. The word philosophy did not just mean jargon and abstract thinking (as it does now). Therefore, it was not necessarily limited to a few experts.

Over time, schools of philosophy (that is, of wisdom) developed. Here again we can see the importance of silence, for the word school meant stillness or a form of leisure and quiet attention that allowed for learning. Each specific school taught its own practices to engage with the world in a deep way in order to understand it.

In fact, ancient and pre-modern approaches to thinking had two components. Ancient thinkers carefully watched how their minds worked and concluded that there was a part of the mind that used reason, logic, words, ideas, and concepts to come to know and analyze things.

Yet this way of knowing, while important, was seen as secondary and only a help to another, deeper way of knowing that they noticed. This way of knowing was seen as a “higher way” of knowing – a more foundational and primal way of engaging and knowing the world. This way was considered the pinnacle of the mind. It was a type of thinking and knowing that is more closely related to perception or intuition. A true knowing, yet not with words and ideas.

In other words, it was silent.

The “Blind Spot” That Gives Us Sight

Becoming aware of this very basic foundation allows us to glimpse how our own minds work and to see that Silence (with a capital S) is not just any practice or activity. Silence is profoundly rooted in knowledge — indeed, in knowing anything. Whether we seek to “know thyself” as the ancient Delphic oracle once mandated, or to know the world, Silence and knowledge are indelibly linked.

Further, the intentional attentiveness to Silence opens up the transcendent aspects of knowledge and being human. In crossing the threshold of Silence the realms of the metaphysical, aesthetic, and ethical all become present as categories to explore and evaluate. The creative impulse that has perpetually appeared in human culture and manifested in its religious and artistic expressions appear here too.

It is here, in Silence, that prayer and contemplation connect. To know God, to know our faith, we turn to contemplation recognizing that it is a type of knowing that is much more immediate to life as it really is and not confined to words or ideas. It is a knowing through participation and encounter. These are all topics that we are exploring in our new podcast, Encountering Silence.

Unfortunately, as Western culture developed, the focus on Silence as an actual practice that is foundational to human knowing eventually became overshadowed by the knowledge we gained — by the words used, the technology developed, and the self that one becomes aware of when one experiences anything at all.

A normal working mind flows in and out of silence continuously as we come to know things — but over the centuries, a constant focus on words, ideas, logic, techniques, and technology has made us misunderstand the process of knowing and how we come to know. Now silence may better be thought of as a kind of blind spot of the mind. Just as the end of the optic nerve where it joins the retina creates a blind spot in each eye but is absolutely essential to seeing, so silence is essential to knowledge, although we often remain “blind” to its role in human cognition.

Without the optic nerve, we could not see at all — thus, in a strange twist, blindness is the very ground of vision. Likewise, a form of unknowing – the shift away from words, thinking, concepts that we currently consider knowledge – is the foundation for knowing.

We need to allow for more silent unknowing in all educational spaces so that we can work with how the mind naturally comes to know.

It is time to expand our minds and notice the blind spot. In recovering this aspect of the mind and putting it back on our mental maps, we will be more able to give our selves over to this practice and more authentically engaged in the pursuit of knowledge and wisdom in all aspects of our lives.

If you’d like to explore these ideas further, here are several books I recommend:

- Maggie Ross, Silence, A User’s Guide — Volume I: Process and Volume II: Application

- Iain McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World

- James P. Danaher, The Second Truth: A Brief Introduction to the Intellectual and Spiritual Journey that is Philosophy

Today’s guest post is by Kevin M. Johnson. A self-described recovering academic, Kevin is an independent scholar, writer, and speaker who explores the recovery of contemplative knowing in his work, in university settings, church settings, as well as online. Kevin is one of the co-hosts (with Carl McColman and Cassidy Hall) of the Encountering Silence Podcast. Connect with Kevin at his website, www.kevinmichaeljohnson.com.

Today’s guest post is by Kevin M. Johnson. A self-described recovering academic, Kevin is an independent scholar, writer, and speaker who explores the recovery of contemplative knowing in his work, in university settings, church settings, as well as online. Kevin is one of the co-hosts (with Carl McColman and Cassidy Hall) of the Encountering Silence Podcast. Connect with Kevin at his website, www.kevinmichaeljohnson.com.

Enjoy reading this blog?

Click here to become a patron.