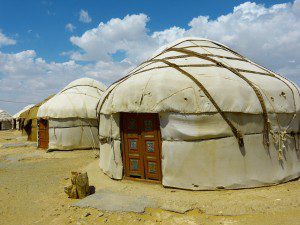

Once upon a time, a man who had two blankets, and a tent of his own, and enough meat to get him through the winter was rich. Today, a man who has only two blankets, nothing but a tent to live in, and just enough meat to get him through the winter is considered extremely poor. The rich man in the tent never thought of himself as poor. He didn’t look with envy on other men and didn’t feel the stigmatization of being of the lowest class. He didn’t think, “Look at me, I have not a computer, or electric heating, or running water, or many delicacies for the table. Woe. Alas. For I have been born into a century of poverty and privation.”

Most of the suffering associated with poverty is the suffering of feeling poor and the fear of being treated like a poor person. People tend to stereotype those who are beneath them on the social ladder as stupid, lazy, and uncouth. The rich habitually treat the poor as second class citizens and have done so since Scriptural times.

“The proud man thinks humility abhorrent; so too, the rich abominate the poor” (Ecclus 13:20).

Judgements of this sort are traditionally based on class distinctions. We tend to think that these distinctions no longer exist in “the land of equal opportunity,” but this is only because these distinctions are now tacitly understood and silently maintained. For example, most municipal planners take the trouble to ensure that people living in cities are stratified according to class. Zoning bylaws are used to control and corral poverty, but it is not just that the poor are ghettoized. The middle class, and even the rich, are also pushed into isolated ghettos where they are functionally prevented from having access to the wider range of social conditions that exist within the same metropolitan sphere — often within blocks of one another. This is good for commerce because it deprives people of a sense of perspective and wards off the danger of pricked consciences and social responsibility. The rich man will always find it much easier to ignore Lazarus if, instead of languishing on his doorstep, Lazarus is politely shoved into an out-of-the-way slum where the rich man need not see him.

The segregation of the classes creates the illusion of poverty within spheres of affluence. People tend to have the most contempt for those who are only one or two rungs below them on the social ladder, whereas they feel pity for those who live further down. This creates intense personal anxiety about any diminution of one’s social status.

The cure for this insular obsession with keeping up appearances is solidarity. Solidarity is very different from pity. When rich Westerners wring their hands about the plight of war orphans, that is pity. When rich Westerners fly to war-torn countries and put their bodies in the way of the guns, knowing that people will wake up and pay attention if an American citizen gets shot, that’s solidarity. It means entering into other people’s suffering in order to have a genuine understanding of what their experience is like, and it means making use of one’s wealth and of the status and influence associated with wealth to improve the conditions of the less fortunate.

Gandhi did this. He traveled all over India by train, riding third class. By riding with poor people, he learned about their lives and gained a real experience of what it was like to suffer the privations that they were suffering. He concluded that “the people in high places…who generally travel in superior classes, [should] without previous warning, go through the experiences now and then of third class traveling. We would then soon see a remarkable change in the conditions of third class travelling and the uncomplaining millions will get some return for the fares they pay under the expectation of being carried from place to place with ordinary creature comforts.”

Those who have actually lived with the poor and shared their poverty do not feel pity. This is because the actual experience of suffering bears almost no relationship to the imaginary experience of suffering: the idea of poverty is much harder to bear than actual poverty. When we look upon “the tragic spectacle of misery and poverty that people tend to ignore in order to salve their consciences” (Populorum Progressio), what we feel is guilt. Pity is not a form of compassion, but a form of self-accusation. The burning in the heart, the tears welling up in the eyes, the sinking feeling in the gut when you look at an image of a starving child is in no way similar to the hunger and desperation that the child feels. If you get people from your parish to sponsor you to go to Africa and suffer in solidarity with that child, you won’t feel anything that is even remotely the same as what you feel when watching the World Vision commercials.

“In economic matters, respect for human dignity requires the practice of…solidarity, in accordance with the golden rule and in keeping with the generosity of the Lord, who ‘though he was rich, yet for your sake…became poor so that by his poverty, you might become rich’” (CCC 2407). Solidarity creates a sense of perspective. Poverty voluntarily accepted is not that difficult to bear. Even if you are cold and hungry, you still have all of your faculties, and all of the good things of the earth to cheer you. If you have experienced this, it makes it a lot harder to get really worked up about trifling privations. This perspective does not, however, lead to carelessness towards others. In times of plenty, we tend to get relatively little out of our riches: the thought of losing them makes us anxious, but the fact of owning them gives little joy. Those who have practised solidarity understand how the poor feel about receiving the things that they have been hoping and praying for. Instead of giving out of a sense of guilt or pity, they give because they realize how much more joy the poor could be getting out of their wealth than they are getting out of it themselves.

[Excerpted from Slave of Two Masters]

Photo credit: Pixabay