Art is not merely a matter of faithfully transcribed inspirations. There is also a large portion of the self that must enter into the work. The inspiration behind Michelangelo’s David is something from outside, something that he feels as being in the marble: “Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.” But we cannot explain David purely in terms of the block of stone; it is not difficult for the perceptive viewer, present or contemporaneous with the artist, to notice the sublimated homoeroticism in the exquisitely sculpted youth.

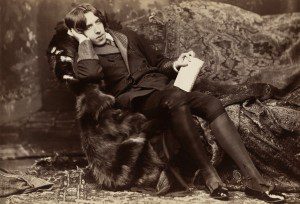

Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Grey is, in part, an exploration of this theme. Basil creates a portrait of young Dorian, but he is terrified to showcase it because he feels that he has put too much of himself into the painting. Again, the hidden secret is homoeroticism — and Wilde’s contemporaries were not slow to recognize Oscar in Basil, nor to deride Dorian Grey as a scandalous novel upon its publication.

The gay artist is not alone in hoping that his secrets will somehow, impossibly, stay in the closet. Every artist outs him/herself. Good art requires a marriage of inspiration and honesty: the artist must take this thing that is from outside, and make it personal. Many of the truths that need to be told are intensely uncomfortable. The artist who portrays darknesses with which (s)he is unfamiliar will always seem callow or superficial to those who actually understand. The allegedly Christian husband in Margret Atwood’s A Handmaid’s Tale does not ring true, he is a stereotype, a person that Atwood doesn’t understand, a man who could not possibly exist. He is no more convincing than the drug addict in a Church basement morality play, or The Peculiar Purple Pieman of Porcupine Peak (rat ta ta ta ta ta ta ta ta!)

The artist who portrays vices, dark secrets, shameful realities with which they are too familiar, on the other hand, courts the scandal mongers. Audiences are quick to associate the artist with the character – they say “As Shakespeare revealed, ‘Life is but a walking shadow…full of sound and fury signifying nothing’” Instead of, “As Macbeth said…” An artist who reveals the world of drug addicts is assumed to be a drug addict. An artist who writes from the perspective of a racist character is presumed racist. Even if you don’t actually suffer from these vices, if you portray them too well, too honestly – if you go too far in actually putting yourself into the shoes of another person and have genuine sympathy and compassion for their experience you are sure to end up accused of being in cahoots.

The reason for this is that most of the great artists actually do honestly portray their own vices. Byron didn’t merely dream up stories about Don Juan while sitting chastely at home with his wife and parakeet. Dostoevsky did not write The Gambler informed by years of quiet, disinterested research and interviews.

Photo credit: Pixabay