I’m usually not a big fan of contemporary writing about the Saints. I like the Golden Legend, not because I believe the stories but because it’s a great read and it offers a fascinating glimpse into Medieval Christianity. I enjoy St. Jerome’s outlandish tales of garish martyrdoms. I tolerate Butler’s because it’s the book about the Saints. But I’ll be honest, for the most part when I want to know who the patron Saint of gardening is so that I’ll have a middle name for a baby whose birth was induced by hilling potatoes, I mostly just rely on Wikipedia.

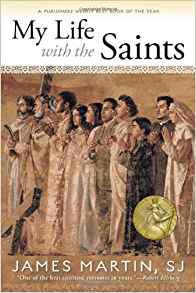

So I picked up Fr. James Martin’s My Life with the Saints more because of the author than because of the subject matter. I’d seen enough of Fr. Martin’s work elsewhere to feel reasonably confident that I would be interested in what he had to say. The promise of a book that dealt as much with the author’s relationship with the Saints as with the holy men and women themselves also appealed to me.

The main difficulty that I usually have with books about the Saints is that they tend to appeal to a fairly sentimentally pious demographic. There’s nothing wrong with that, per se. The preference for sentimentality in art, including religious art, is not inherently inferior (or inherently superior) to a preference for ethereal creepiness or hard-nosed realism. Some people like Precious Moments and love to hear “On Eagle’s Wings.” Others prefer ossuaries and “Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence”. These are aesthetic, not moral, differences.

I just don’t happen to have much of a spiritual sweet-tooth, and I find that most writing about the Saints is not to my taste.

Fr. Martin’s book is therefore refreshing. It’s not overly pious. It’s not gimmicky. There’s no cute premise. It’s just a book about the holy people who have inspired him. The stories of their lives are interwoven with memoir, so you get a balance that makes the Saints easier to relate to.

For example, in the chapter on St. Bernadette he draws attention to the fact that the Saint refused all of the gifts that were offered to her as a result of her visions. Later, in the same chapter, Martin mentions being invited out to lunch by a reader who wanted him to be chaplain on a pilgrimage to Lourdes. He accepts the invite because he’s “always happy for a free meal.” This counterpoint makes it easier to love Bernadette because it draws attention to the fact that we can admire her virtues, even if they are not identical to our own.

The Saints as Martin portrays them are not perfect airbrushed people immortalized in plaster and placed upon a pedestal. But nor are they gritty, flawed, semi-neurotic people with dark secrets. They are just very, very good human beings. By avoiding the excesses of pious legend Martin is able to show how heroic virtue can manifest in people who are not superhuman.

To me, this is the most important achievement of this book. Too often, the Saints come across as being a different order of being. They are too idealized, and so they can only ever be lionized or crucified. We can’t relate to them as friends, only as ideals.

Instead of idolizing the Saints, Martin sympathizes with them. He imagines what some of their trials must have been like, and instead of focusing only on the grand theatrical struggles he enters into their little day-to-day frustrations. This makes it easier to imagine how we might imitate someone like Joan of Arc, or Therese of Lisieux, or Francis of Assisi. After all, most of us are not called to the convent at 14. We don’t hear voices commanding us to lead armies. We aren’t the founders of great religious movements.

We can, on the other hand, imagine the frustration of being snubbed and disposed of by those who we once helped. We all know what it’s like to suffer ingratitude for our labors, or to have people pester us over and over and over again for the same answers to the same questions that we’ve gone over a hundred times. Showing how the Saints bore their little crosses with a combination of patience, good humor, and occasional sharp wit, offers us something that we can actually imitate in our ordinary lives.

Finally, Martin brings all of this together by showing how the Saints have helped him in his own spiritual growth. This means that alongside the fantastic exploits we have the evidence of a much more quotidian type of holiness. Father Martin is someone that we relate to directly. He drives a car, he has ordinary doubts and questions, he gets caught up in silly quibbles about who is going to piously renounce the good room at the retreat house. He has the humility and good humor to recognize his foibles as foibles, without ever droning on self-importantly about what a terrible sinner he is. His memoir illuminates his own personality without being self-indulgent or attention seeking.

By giving us the gift of his own relationship with the Saints, Martin provides us with an invitation. It’s kind of like someone introducing you to a new friend. I found myself softening towards Saints that have always intimidated me, like Ignatius of Loyola, and growing in love towards old friends who have gone before me on the way.

If you’re looking for a pleasant, readable, and relatable introduction to the diversity with which sanctity manifests itself in human lives, this is a book that I would highly recommend.

Stay in touch! Like Catholic Authenticity on Facebook: