I promised that I would talk about the difference between infallibility and authority, and why I’ve decided to work on rebuilding trust in and with the Church rather than simply abandoning my faith in favour of another (ideally less fraught) relationship.

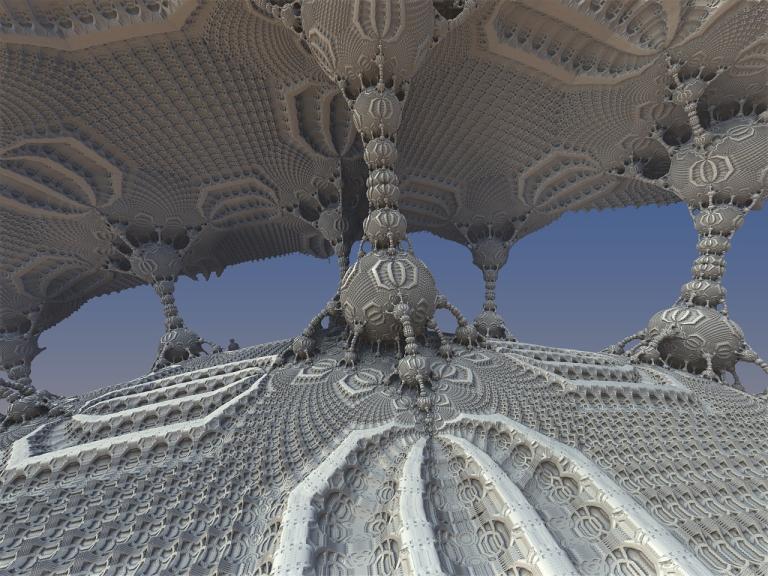

To explain this, I need to begin by explaining how I see humanity and human history. Basically, I conceive of the human world as fundamentally fractal in nature. So if you look at an individual human being, a sub-culture, a culture, an institution, a nation-state, a civilization, or indeed the whole human race throughout all time and history, you are looking at innumerable different and unique iterations of the same basic formula.

So this means that if you look at an individual and at a collective, you’re going to see the same types of patterns borne out. They’ll vary based on temperament, personality, autonomy and circumstance, but I do think that if you want to understand large-scale organizations of human beings it’s helpful to think of them as being analogous to individuals. They follow similar processes of maturation, display similar faults and similar virtues, and are motivated in similar ways.

And of course, because you have a very large number of different scales of human organization all functioning together within the human collective, you have innumerable different iterations of the fundamental human pattern, all at different levels of development and maturity, all playing out and interacting simultaneously, and all contributing to making up the larger-scale patterns of which they are a part. If you try to picture a four-dimensional fractal that unfolds in time as well as space, that should give you some idea of how I see this.

I see the Church in a similar way. On one level, She’s a woman growing towards maturity in expectation of becoming the eschatological Bride of Christ. On another, She is a mother attempting to guide and nurture a large brood of frequently disobedient children. The Church is also the Body of Christ, and as such has already realized (in some sense) its identity as One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic. On another level, the laity and the hierarchy are two, distinguishable bodies within the Church and they exist in a relationship which I think is basically analogous to marriage.

All of these different analogical relations reveal different types of truth about the nature of the Church, and the relationships between different individuals and groups within the Church. But for obvious reasons, it’s ridiculously difficult to reconcile all of the different levels so that they come together in a coherent whole. Indeed, I would argue that a significant part of the mystery of the Church is the fact that it’s actually quite hopeless for anyone, from a merely human vantage point, to appreciate how all of these interlocking relationship cohere; that’s something that can only be appreciated from a God’s-eye-view.

So, thinking about my own situation vis a vis the Church, some of these relationships are in conflict, others are not. My relationship to Christ, for example, is not problematic at the moment. When I approach Him in prayer, I receive that “peace [which] the world cannot give.” When I’m at Mass, and I gaze on the Eucharist, I feel an incredibly intense sense of love and communion with Him. I draw nourishment from His presence, and I don’t feel at all like I am out of place as a member of His body.

Nor do I feel alienated from the Church as a young woman developing towards maturity, a human Bride who God has made to be eternally united to Him in beatitude, and who is stumbling (in a very normal human way) towards the realization of Her own identity and towards the cultivation of virtue.

I think of my own contribution as merely part of the morass of conflicting thoughts and impulses that characterize the interior life of a human being, and conceive of “thinking with the Church” as a process of trying to bring these interior conflicts to a satisfactory conclusion that is commensurable with truth. In this capacity, I love the Church and also (even though I’m sometimes pained by the tensions) I deeply value the thoughts and ideas of those who disagree with me. After all, I don’t find that I’m able to come to good decisions in my private life without looking at a problem from all angles, and I think one of the great strengths of the Church is that we are able to engage in this type of lively internal dialogue without destroying the integrity of our common identity.

So far as my relationship with the Church as mother goes, there is a little more tension. Theologians have spoken of a distinction between the “teaching Church” and the “listening Church.” This more or less describes a mother/child type relationship, and it’s one that is presently conflicted not only in my own life, but throughout most of the Western Church. My best theory here is that Western culture, as a whole, is basically going through a kind of collective adolescence and that the Church, as mother, is experiencing precisely the kind of problems that we would expect if this were the case.

I mean, adolescence is a difficult transition both for the child and for the mother. On the one hand every teenager wants a degree of autonomy that they’re not really ready for, and on the other hand most mothers find it difficult to grant their teenage children the degree of freedom that they really are entitled to. Parents of adolescence often err in overstating their authority and in setting undue or paranoid restrictions on their childrens’ behaviour; adolescents often err in ignoring or rejecting the wisdom of their parents and in breaking rules that are actually just.

I would add, here, that I think it’s a distortion to identify the laity as the child, and the hierarchy as the parent. There are clear instances (the sex abuse scandals being the most prominent one at present) where the hierarchy has acted like a very, very bad child and has gone to great lengths to avoid being caught, while the laity has played the role of responsible adult, applying discipline through the instrumentality of secular powers. Everybody in the Church, from the Pope to the person who only shows up at Christmas, has to sometimes humble him or herself, to be as a little child. Also, all of us in the Church have to “put away childish things” and behave like adults, taking responsibility for our own faith and for the good of the Body of Christ.

These are all ways in which I relate to the Church, as a Catholic, in a way that I feel is authentic and not especially problematic. I recognize, for example, that a body has to function in a unified way: there has to be some coordinating centre to an organism, and the whole has to function (as much as possible) in harmonious accord with itself or else you end up with problems such as illness or inactivity. This means that my own personal intellectual freedom has to be placed at the service of a broader discourse within the Church, and it has to ideally seek out a reconciliatory path towards truth through dialogue, rather than simply asserting itself confrontationally. It also means that I should try, as much as possible, to carry out the positive precepts of the Church to the best of my ability.

I also recognize that in relation to the whole Church I need to exercise the humility of a child. Part of the reason why I love the Church is that I believe the pursuit of truth is best undertaken as a collective enterprise, so that each person may have their individual blind-spots corrected, and so that private, ulterior motives have less opportunity to cloud one’s judgment. In cases where my private opinion contradicts the collective wisdom of the rest of the Church, I need to be seriously open to the probability that I am just wrong. I should approach the Church’s teaching with the spirit of one who is prepared to learn, and who does not consider herself to be already in possession of the truth.

Finally, I do believe that the Holy Spirit guides the Church and I do trust in Christ’s promise that the Spirit will lead us into all truth. I think that there is a sense in which infallibility is real: specifically, that all people have an instinct for truth which is imprinted on our hearts, and that when we come together in good will to pursue the good, the true and the beautiful, God leads us unerringly towards it.

I would, however, add the caveat that this is a process, and that the insights which seem true at any given point may simply be closer to truth than whatever was previously believed. So for example, when one of the writers of Sacred Scripture recorded the command “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth” he was not recording a truth in the absolute sense (otherwise Christ’s command to “turn the other cheek” would be nonsense). Rather, this dictum was a step in the right direction: whereas the Israelites had previous been quite enthusiastic about Samson slaying “heaps upon heaps with the jawbone of an ass” as the climax of a petty conflict, now they were required to behave with a sense of proportion in meting out vengeance.

Anyway, in rare cases, when some truth has been enthusiastically embraced by the faithful and the hierarchy alike over a very long period of time, I do think it’s reasonable to propose that the Pope has the authority to define that truth as dogma. Referring to this as “Papal infallibility” however, seems misleading as really, in such cases, the ability to discern truth belongs to the whole Catholic communion. The Pope merely articulates the consensus of the Church, genuinely acting as the “servant of the servants of God.”

Which leads us to the really conflicted relationship in my faith-life, which is that of laity and hierarchy. But that’s a big issue that requires a post of its own.

Image credit: pixabay

Stay in touch! Like Catholic Authenticity on Facebook: