Review by Maura Zagrans

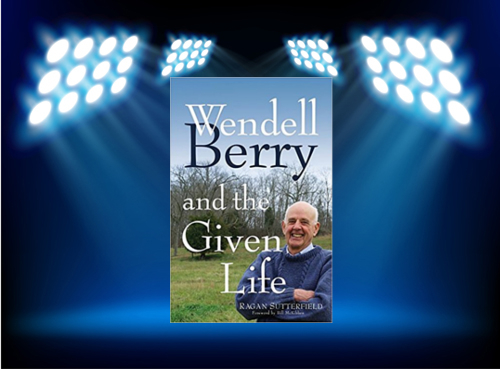

If I could, I would thrust a copy of Wendell Berry and the Given Life by Ragan Sutterfield into the hands of everyone I know. Here’s why:

Sutterfield’s book is a terrific introduction to an esteemed man of letters. Wendell Berry is a poet, novelist, essayist, conservation activist, and pioneering agrarian who advocates for sustainable agriculture. Thus Berry is a man whose legacy is equally remarkable for his literary writings as well as for his pioneering work and continuing leadership in the field of responsible agrarianism. If you patronize local farmer’s markets, or if your default setting inside grocery stores is to choose local organic produce, then you have Wendell Berry to thank.

Sutterfield maintains that Berry’s work is important because it speaks to our moral integrity at the same time as it addresses our mortal future. You might say that Berry is Rachel Carson 2.0. Berry brings science, generations of farming history, startling literary brilliance, and a deeply Christian point of view all to bear on discussions of the conservation crisis. On one level, it is crucial for more people to hear Berry’s clarion call to rewind our culture, to back away from industrialism, purely in the interests of survival. On another level, Berry speaks to our moral culpability in the ruination of families, communities, and the planet as a result of our failure to obey the most basic of God’s directives to love thy neighbor.

Sutterfield argues that Berry is a sage, a lamenting prophet who connects the dots between how we live and the state of our souls. Was this what God intended when he handed over his creation to us? Is this the role we were meant to play as caretakers? Sutterfield distills a diverse body of work published over the course of nearly sixty years; in so doing, he performs the invaluable service of making the ideas of a great Christian thinker more accessible to a wider audience.

Would anyone dispute that our souls are mirrors of our lives? That the choices we make as we journey through this one life we have been given become a kind of compilation of who we are? That whom we love or choose not to love imprints a chronology of how closely we followed God’s basic instructions? Sutterfield takes the top notes of Berry’s writings and uses them to compose an undeniable wake-up call. If you think of yourself as a Christian, you will read this book and think again, this time from within Berry’s point of view. Berry digs deep into the Bible as well as into the humus of the land to argue that every creature is connected, that both the known and the unknown play indecipherable roles in the successful turning of the earth. Using the looking glass of Berry’s life and life’s work, Sutterfield helps us see how the whole of our lives represents choices to love or not love. Suddenly we understand that we have no right to feelings of smug satisfaction as we sit in our church pews.

Sutterfield uses Berry’s poetry, prose, and fiction to build a platform from which we can see the panorama of life through Berry’s “deeply Christian” vision. He points out the ways in which Berry is quietly yet convincingly Christian, how Berry lives from the Gospels and by the precepts set forth in the Sermon on the Mount, and how he maneuvers modern culture with the ancient mindset of a peacemaker. He adds, “Berry’s work is, in a way, evangelistic, not only in the ideas it puts forward, but in its spiritual call.”

Sutterfield goes further, arguing that Berry is a modern day prophet, one to whom the banner seems to have been passed by none other than St. Benedict himself. Sutterfield writes of Berry, “Like St. Benedict, he provides a vision that many people respond to not only with their minds, but with their lives.” In seeing Berry as a contemporary St. Benedict, Sutterfield proceeds with the kind of respectful deliberation that Berry himself likely employs during his Sunday hikes stepping through the wild and sacred soil of his old Kentucky farm. Sutterfield strikes a nice balance between objectivity and reverence. There is no doubt that this author is an admirer of his subject but he never crosses the line into hagiography.

Sutterfield is a skilled stylist, his writing often lovely, as when he introduces the topic of earth as God’s kingdom: “Up the hill, there is a stand of timber, uncut in the last century, its older members too large for an embrace.”

His writing is also well crafted, as in the extraordinary chapter on Language. Here, Sutterfield begins by exposing the lying ways of the monstrous agribusiness company Monsanto, whose public-relations campaigns are designed to deceive potential customers about the actual impact of the pesticides and genetically modified crops Monsanto sells. Sutterfield then considers truth and lies from the Christian tradition as reflected by theologians such as Stanley Hauerwas, St. Augustine, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer. In arguing that Berry properly stands in their company, Sutterfield identifies Berry as “a writer worried about his words—he is careful with and of them, but this isn’t simply because he wants to clearly communicate or elicit a particular emotion or response. His care is rooted in his desire to be truthful in his language and thus in himself.” Sutterfield writes, “For language to function, it must dance between the inner and outer, it must bring the self home.” It is to his credit that Sutterfield is able to reveal how Berry’s work does just that.

For all of that, what I love most about this book is the way Sutterfield brings us to the Berry banquet table where he has laid out the quintessence of a modern day hero for us to sample and savor. Some morsels to whet your appetite:

- “We must learn to live a given life in a given world.”

- “The more coherent one becomes within oneself as a creature, the more fully one enters into the communion of all creatures.”

- “Love is never abstract. It does not adhere to the universe or the planet or the nation or the institution or the profession, but to the singular sparrows of the street, the lilies of the field, ‘the least of these my brethren.’”

- “Pleasure is, so to speak, affection in action.”

- “The ‘environmental crisis’ has happened because the human household or economy is in conflict at almost every point with the household of nature.”

- “The Bible’s aim, as I read it, is not the freeing of the spirit from the world. It is the handbook of their interaction. It says that they cannot be divided; that their mutuality, their unity, is inescapable; that they are not reconciled in division, but in harmony.”

- “The idea of the exclusive holiness of church buildings is, of course, wildly incompatible with the idea, which the churches also teach, that God is present in all places to hear prayers.”

- “There are no unsacred places; / there are only sacred places / and desecrated places.”

I’m no theologian, but the thought that Berry is indeed a most likeable prophet occurred to me years ago. Chalk it up to an overactive social conscience. In 2006, for example, after having read Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma, I was inspired to launch an in-depth study of America’s shockingly toxic, unforgivably cruel food chain, and I’ve never regretted the new eating mantra I was inspired to adopt: Nothing with a beating heart. It was shortly thereafter that I discovered Berry’s poetry and became a fan. His prophetic vision is one that resonates with me. One of the precepts by which I live is the simple awareness that we’re all in this together. Berry’s work trumpets this philosophy. Not surprisingly, then, Berry had me at the title page. These days, I read his poems as if they were prayers because, well, for me, they are.

To read Wendell Berry and the Given Life is to allow a beehive of disquieting awareness to be stirred. What we come to see is just how unholy we have allowed our lives to become. Which brings us to the elephant in the room. What can one person do given the profundity of the mess we have made? Wisely, Sutterfield acknowledges this issue. “The question for many of us is how to translate this vision to our places, places already covered over in concrete, obscured by the anonymity of strip malls . . . The answer, as Berry has on occasion said, is that we must begin. We must make a start.”

I met Berry once, on 10 September 2013, when he and his longtime friend and collaborator Wes Jackson came to Oberlin College. I recall that a student asked the question about what he could do to live a more conscionable life within the context of attending college in a small town in Ohio. Exactly as Sutterfield reports, Berry simply encouraged the student to figure it out and begin.

Following the lecture, Mr. Berry and I spoke for a couple of minutes. I told him that my dad had grown up on a tobacco farm not far from Port Royal, and that we had visited those rolling, verdant hills many times throughout my childhood. His face lit with pleasure. He smiled a smile so warm and unguarded it felt to me as if in that moment we had suddenly become tree house buddies, and my heart suffered a stab of recognition. He reminded me so much of my late father. Was it something about Kentucky that put that familiar twinkle in the eyes of her native sons?

Those who know me know that I’m not very good at keeping my enthusiasm in check. I’m a passionate person who wraps her heart around the whole of life fiercely, joyously, completely. Given my keen admiration for this book, the challenge for me in writing this review was to talk about Wendell Berry and the Given Life with some modicum of objectivism and restraint.

And so, if you and I meet one day and I thrust a copy of this book into your hands, please expect that I will also beg you to call me up after you have read it so that we can dive deeply into a meaningful dialogue about how we can sculpt our personal worlds to create Wendell Berry-esque lives.

What does it mean to live in a Wendell Berry sort of way? It means that we should live as if we understand that we are here for a profound purpose. This purpose is to accept the given gift of life by conducting ourselves responsibly and appreciatively. In the end, the lives we create will be like virtual bouquets presented back to God as an expression of gratitude.

It seems to me that this is pretty much the only decent thing to do when gifted with so extravagant a gift as life.

For further information about Wendell Berry and his important work, visit http://berrycenter.org/

And, for the record, I think that Ragan Sutterfield’s Wendell Berry and the Given Life belongs on this Website’s Wendell Berry Booklist.