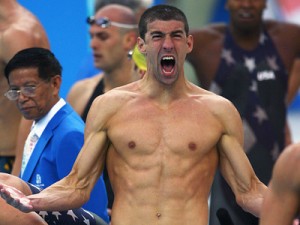

What do Michael Phelps, the new “Fab Five” and the U.S. men’s basketball team all have in common? They all help us suppress (and repress) our existential anxieties: Our unsettling, subconscious realization of finitude, our fear of death, and our fear of the cultural “other.”

It’s been interesting reading through Richard Beck’s The Authenticity of Faith during these Olympics. Beck masterfully unpacks what he sees as the greatest apologetic challenge to religion in the present moment: The seemingly coherent (and at least partially persuasive)  explanation of the “functional” instrumentality of religion. To put it bluntly, religion helps us get along psychologically and emotionally in a world that otherwise might seem existentially intolerable: a world characterized by suffering, randomness, meaninglessness and punctuated by the inevitability and universality of death. This is, of course, Freud’s massively significant challenge to the normativity and authority of religion. Freud said that humans need religion (well, most of us do)–or at least have been trained to think we need religion, to survive or to thrive. And in a collective, Darwinian fashion, religion functions as a buttress for the survival of our species.

explanation of the “functional” instrumentality of religion. To put it bluntly, religion helps us get along psychologically and emotionally in a world that otherwise might seem existentially intolerable: a world characterized by suffering, randomness, meaninglessness and punctuated by the inevitability and universality of death. This is, of course, Freud’s massively significant challenge to the normativity and authority of religion. Freud said that humans need religion (well, most of us do)–or at least have been trained to think we need religion, to survive or to thrive. And in a collective, Darwinian fashion, religion functions as a buttress for the survival of our species.

It’s not only religion that functions this way. Lots of other cultural phenomena are put to use in managing (suppressing / repressing) our collective existential terror (Ernest Becker). So back to the Olympics: What better way to forget about our mortality than by watching someone do something heroic–and seemingly immortal? When fellow human beings push the limits of the humanly possible it gives us a sense of exuberance and of momentary invincibility. I feel that way when I see swimmers chasing the yellow world-record line (Soni, anyone?) What’s a world record if not a kind of quest for immortality? We want to follow in their wake into eternal significance — or at least forget our finite limits for a moment.

We had no idea Phelps and Lochte and Douglass and Wieber were doing all that, right? But that’s precisely the point. It only works if we aren’t aware that’s it’s working–if it stays in the depths of our subscious–or if we’re good at stowing away the realization and getting on with our “workaday lives” (Beck). So in the spirit of NBC and the Today’s shows Missy Franklin promotional gaffe, I’m spoiling it.

I know what you’re thinking: “The Olympics as existential narcotic?” It  sounds disrespectful or at the very least cynical. I feel that way too. It’s as if a beautiful, celebrated, and “pure” event of human excellence gets whittled down to a brute instrument of psychological repression. Surely that’s not a sufficient way to think about the greatest athletic stage in the world.

sounds disrespectful or at the very least cynical. I feel that way too. It’s as if a beautiful, celebrated, and “pure” event of human excellence gets whittled down to a brute instrument of psychological repression. Surely that’s not a sufficient way to think about the greatest athletic stage in the world.

That’s a valid objection. The explanatory success of science is helpful–but limited–in getting at the core reality of an event like the Olympics (and even more limited in explaining the depths of religion). We might say that, as with the experience of art, or music, or love, or prayer, in the Olympics we experience (perhaps) traces of transcendence, or real presences (George Steiner) which defy a “merely” psychological or solely social science analysis. Same thing is true, though to a higher degree, of religion. Religion, in fact, is the result of human response to the experience of divine presence. And this is a major implication of Beck’s analysis–that Freud cannot whittle religion down to pure, psychological function. In the end, the Olympics might resist such reduction, too.

In any case, it’s been fascinating to reflect on the Olympics through the lens of “existential narcotics.” Who needs drugs when you’ve got Michael Phelps, Aly Raisman and Kevin Durant speeding us off into immortality?