(Wikimedia CC; click to enlarge.)

I like a stroll on the beach as much as anybody, and we’ve done a bit of that here. But the real point of coming to southern Spain was to spend some time poking around the remnants of the Islamic golden age in al-Andalus.

On Friday, as I’ve already noted here, we visited the very ancient mountain town of Ronda.

On Saturday, we went to Córdoba, where, after parking in a structure located right by a larger-than-lifesize statue of the great twelfth-century Córboban philosopher and Aristotle commentator Ibn Rushd (Averroës) — some of whose work was published by BYU’s Middle Eastern Texts Initiative (METI) while I directed that project — we first visited the Alcázar de los Reyes Cristianos (“Alcazar of the Christian Monarchs”). The term Alcázar comes from the Arabic Arabic word القصر (al-qasr, “the Palace”); the fortress was one of the primary residences of Isabella I of Castile and her husband, Ferdinand II of Aragon. It was here that Christopher Columbus sought, and eventually received, the support of the two monarchs for his world-historical voyage to the Americas in 1492.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Even more interesting to me, though, was the iconic Grand Mosque of Córdoba, built on the site of a former Visigothic church by the great eight-century ruler ‘Abd al-Rahman I, whose remarkable life deserves a book if not a movie, and his early successors. Following the Christian reconquest of the city, it was transformed into the city’s cathedral, a status that it still retains today. (To my surprised delight, an organist in the mosque/cathedral was playing Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D-minor, one of my very favorite pieces of music. It was odd to hear it in such a setting.)

We also walked through the nearby Jewish quarter, where the illustrious rabbi, physician, and philosopher Musa b. Maymun (Moses Maimonides), a slightly younger contemporary of Ibn Rushd, was born. A statue of Maimonides stands near the medieval synagogue. METI has been involved for years in publishing dual-language editions of his medical works. And — I’m no longer affiliated with my translation project — I’ve read that the current leadership of METI plans to eventually publish an Arabic/English edition of his great Guide of the Perplexed, thus (after a fashion) fulfilling a decades-old dream of mine.

Besides publishing their works, I’ve taught courses centered on Maimonides’ Guide and on Averroës’ Incoherence of the Incoherence and Decisive Treatise. So Córdoba is a big deal for me.

We had a relatively light day on Sunday, including time with the tiny English-language LDS branch in Fuengirola, here on the Costa del Sol. I was the concluding speaker in sacrament meeting.

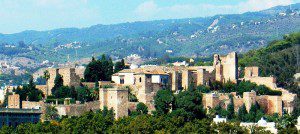

(Wikimedia CC; click to enlarge.)

Afterwards, we walked through the magnificent eleventh-century Alcazaba of Málaga, the best-preserved alcazaba in Spain. (The term alcazaba is derived from Arabic قصبة, qasba, meaning “citadel.”) Ferdinand and Isabella captured Málaga from the Moors after the 1487 Siege of Málaga, one of the longest military campaigns in the Reconquista. Following their victory, they raised their standard atop the “Torre del Homenaje”(the “Tower of Homage”) in the inner citadel.

After the Alcazaba, we paid a lengthy visit to the surprisingly large Cathedral of Málaga.

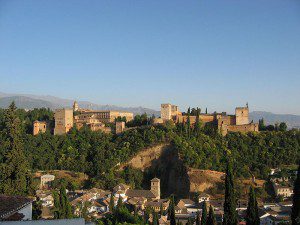

(Wikimedia CC; click to enlarge.)

On Monday, we went to Granada, where we had hired a private guide for the Alhambra and the Generalife. It was well worth it. My wife and I had visited both places before, but he was able to show us things that we hadn’t noticed and to provide background that we hadn’t known. I won’t even try to supply adequate images for these unutterably romantic and beautiful places. Google them. And, if you haven’t visited them yourself, make visiting them a goal.

The Alhambra takes its name rather mysteriously from the Arabic الْحَمْرَاء (al-hamra’, “the red”), while the word Generalife comes from Arabic جَنَّة الْعَرِيف (jannat al-‘ariif; “garden of the architect”). It was the surrender of the Alhambra to Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492 (a very good year for them) that marked the final triumph of the Spanish Reconquista.

From the Alhambra, it’s possible to see a mountain pass in the Sierra Nevada mountains called Puerto del Suspiro del Moro (“Pass of the Sigh of the Moor”). The story behind the name is an interesting one, somewhat blackly amusing: When Muhammad XII, the last Moorish sultan of Granada, was defeated by the two “Catholic Monarchs” (reyes Catholicos), Ferdinand and Isabella, in 1492 and evicted, he and his court reportedly crossed 860-meter pass, from which they were able to take a last melancholy look back at their beautiful home, now lost forever. Supposedly, Muhammad sighed, and a tear ran down his cheek. Whereupon his mother, not one to offer him comfort at so difficult a time, remarked, “It is fitting that you should weep like a woman for what you were unable to defend like a man.”

Zing.

Following our visit to the Alhambra and the Generalife, we went down to the city of Grenada below. We spent a lengthy time in the cathedral there, and topped our time off with a visit to the directly-adjacent Capilla Real, the “Royal Chapel,” where Ferdinand and Isabella — and their ill-starred successors, Philip the Handsome and Joana the Mad (Juana la Loca) — lie entombed.

(Wikimedia Commons)

We had another relatively light day today, visiting the famous Rock of Gibraltar. None of us had ever been there before. Several people had told us not to bother, that it was of no real interest.

We disagree.

It was fascinating.

For one thing, the weather was perfectly clear, so we were able, from high up on the rock, to see the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, Spain and very nearby Morocco (while standing on a territory of the British Commonwealth, which Gibraltar is), Europe and (just across the narrow Straits of Gibraltar), Africa. With its views — the Mediterranean is only eight miles wide at Gibraltar — its Cave of St. Michael, its centuries-old British military tunnels, its curious Anglo-Spanish culture, its fame in Greek legend as one of the “Pillars of Hercules” and an entrance to Hades, its longtime reputation as the literal end of the Earth, and its Barbary Macaque monkeys, Gibraltar is a really interesting place.

Now, lest it be thought that, by visiting Gibraltar, I was taking a pause from this trip’s Arab/Islamic focus, here’s a bit of history: The name Gibraltar is a Spanish corruption of the Arabic Jabal Ṭāriq (جبل طارق), which means “Mountain of Tariq.” This refers to the Umayyad general Tariq b. Ziyad, who led the initial AD 711 invasion of Iberia before the arrival of the main Umayyad force. Gibraltar is the place where he organized his troops for battle upon his arrival across the Straits.

We shared a van and an excellent local Gibraltarian tour guide named Keziah (see Job 42:14) with a nice Indian Hindu family (a physicist and his MBA wife who now both work for Intel in Portland). We even persuaded Keziah to add onto her time with us to take us all out to Europa Point and to the beautiful mosque there that was given as a gift from Saudi Arabia’s late King Fahd. Afterwards, we enjoyed excellent fish and chips at Roy’s, in Casemate Square.

A fantastic day.

Posted from Marbella, Spain