My father died thirteen years ago today.

I still miss him very much. I think about him every day. Certain sights always remind me of him. There are many things that I would like to tell him.

More and more of the people I’ve known and loved, the people who formed me and to whom I looked up, are now gone. The collection of my friends and family on the other side continues to grow.

As has become my little tradition, each year (if I don’t forget what day it is), I post tributes (often what I wrote for their funerals) to my father, my mother, my brother, and my granddaughter. They’re not adequate, and there’s no reason why anybody else should care about them, but I want to do something. So here’s what I delivered just slightly yes than thirteen years ago, haltingly and through tears:

For Dad

Written 30 June 2003

Delivered 3 July 2003 (Rose Hills Cemetery, Whittier, California)

First of all, I want to thank all those who have helped Mom and Dad through these last, difficult, years. The ward. Their home teacher, Gary Walburger. Mom’s visiting teacher, Lou Ann Hatch. Particularly Angelina, Virginia, Blanca, Gus, my aunt Mary, and—most especially—my brother, Kenneth.

I’ve written my remarks out, hoping that I might have a better chance of getting through this. (My initial practice run was not encouraging.) I wrote almost all of these notes while sitting with Dad in the hospital over the weekend, while he dozed—and when it became inescapably obvious to me that his earthly stay could not (and should not) continue much longer.

A totally unexpected stroke left Dad blind six years ago, and deprived him of almost everything he liked to do. He had already been obliged to give up hunting and fishing and golf. Now he couldn’t read. He couldn’t work in his beautiful yard. He couldn’t follow the stock market or research family history. He couldn’t even watch Dodger baseball games or play cards or practice tricks on his pool table. For obvious reasons, he became very fond of a famous old Protestant hymn written by John Newton:

Amazing grace! (how sweet the sound)

That sav’d a wretch like me!

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind, but now I see.

At first, he talked a great deal about getting his sight back. With the passing of the long dark years, though, he mentioned that possibility more seldom, and, gradually, his muscles atrophied and his mind lost its sharpness and he spent more and more of his life immobile, a prisoner of his rocking chair. But he never entirely gave up hope. With touching determination, he hurled his fading memory at stacks of Spanish instructional tapes—over and over and over again. As recently as last Friday, he asked me whether he would ever be able to see again. I told him Yes. What I didn’t tell him was that I expected it to be only in the next life. And now, after his long night of darkness, he can see again. “Someday we’ll understand all of this,” he said to me several times over the past few months. Now the mental fog that increasingly gathered about him and so frustrated him has been burned away by warm, brilliant, loving light. All is clear. In the words of a beloved Mormon hymn, “The morning breaks, the shadows flee!”

John Newton’s “Amazing Grace” contains another verse, far less known than the one I’ve already quoted. Dad was probably unfamiliar with it. But it describes perfectly what has happened to him this week:

Yes, when this flesh and heart shall fail,

And mortal life shall cease;

I shall possess, within the veil,

A life of joy and peace.

More and more, as Dad sat there in darkness, his mind journeyed back to earlier days, to (among other things) life on the family farm in North Dakota. Several times, he told me of the prayer he prayed as a little boy, part ready-made and part personalized:

Now I lay me down to sleep.

I pray the Lord my soul to keep.

If I should die before I wake,

I pray the Lord my soul to take.

God bless Papa and Mama, Nellie, George, Alvina, Clarence, Ernest, and Selmer.

For the past several years, Dad has been the last of that little Scandinavian farm family. All had gone on before him. As I visited with him this past weekend, I found myself unable to pray for his recovery. I could only tell him how much we loved him, and pray that he would be received on the other side by those who loved him at least as much.

I do not believe that he was alone when that time came, when, as he had prayed as a child, the Lord finally did take his soul. I expect that Papa and Mama, Nellie, George, Alvina, Clarence, Ernest, and Selmer were there to welcome him home, in a wonderful reunion with those whom he had “loved long since, and lost a while.”

As I’ve mentioned, I was able to spend much of last weekend—his last weekend—with Dad, something for which I’ll always be grateful. Perhaps because of his medications, Dad was “confused”—that was his word—about many things in his final three or four days. But the quality of his character was as clear as ever. Perhaps even clearer, because, as his conversation grew repetitive, he repeated the things that really mattered to him. At the end, his concerns were about whether he had led a good life, whether he had contributed anything, done some good, whether we had a good relationship, whether we were all close as a family. I told him Yes, on all counts.

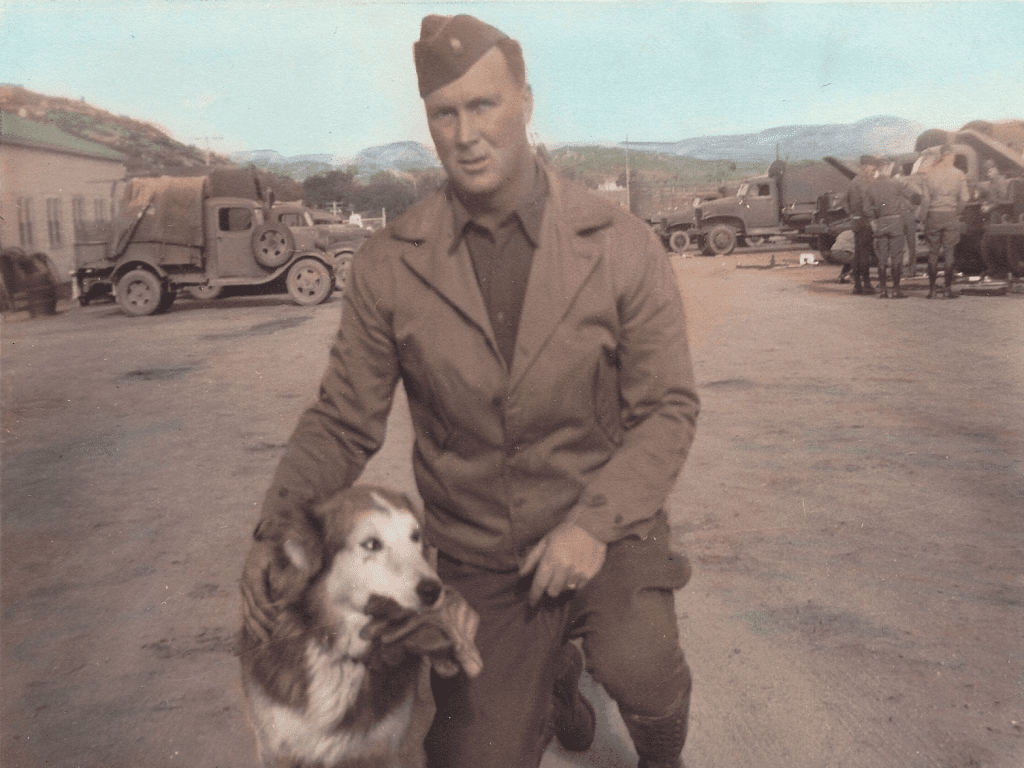

Over his last few days, this veteran of the Eleventh Armored Division, of Patton’s Third Army, didn’t remember military experiences in the Ardennes Forest of Belgium. He didn’t remember the blackout over London, the V-1 and V-2 rocket attacks that he had told me about so often. He didn’t remember his unit’s role in the liberation of the Nazi death camp at Mauthausen, in Austria, which had been such a pivotal experience of his earlier life.

He didn’t remember, until I reminded him, his studies at forestry school in North Dakota, or his stint in Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps, or his pre-war enlistment in the horse cavalry down by El Centro. The old sense of humor was still there, though, when memories came back to him. He thought that his stay in the cavalry would be a short one. But then came Pearl Harbor, and a note from the president telling him that his military career had been extended “for the duration.” Lying on his bed last Saturday, he chuckled at the letter’s cheery opening word: “Greetings!” said President Roosevelt. “That was nice of him!” remembered Dad. And when the physical therapist asked him, on Sunday, what the main problem was, he replied, “I’m getting awfully damned old! That’s the problem!”

Several years ago, Brigham Young University hosted a conference on the “liberators,” the now-aging soldiers who had put an end to Hitler’s concentration camps and freed their few nearly starved survivors. Dad didn’t want to come. But he surrendered to pressure and pleas, and he did. And when, at a concluding luncheon for the conference, the conference organizers asked the veterans to rise, receive a standing ovation, and be given a plaque, he broke down and sobbed. Only once before in my life had I seen him weep so.

Last weekend, as Dad lay pathetically in his hospital bed, he looked all too much like the concentration camp inmates that he had helped to free nearly six decades earlier. The liberator, one of the dwindling number of what has justly been called “the greatest generation,” now himself needed liberation from a body that was, simply, worn out.

A couple of Fridays ago, I spoke with him on the telephone. As I always did, I asked him how he was. “Dan,” he answered in an exceptionally strong and clear voice, “I can’t do anything.” As if he were preparing me for what was soon to follow, he told me that he was ready to go, and that I shouldn’t be sad when he did.

A radio advertisement has been playing in Utah recently, for a performance of the Requiem by Gabriel Fauré. In it, Fauré is quoted as responding to critics who thought his Requiem wasn’t gloomy enough. It was, they said, a kind of “lullaby to death.” Fauré cheerfully conceded that that was indeed exactly what it was. Death, he said, comes as a deliverer. It opens the path to a better place. Certainly, it did so for Dad.

At the end, Dad didn’t really remember E. C. Construction Company, the many factories and streets and neighborhoods that he and his colleagues had helped to build. He didn’t remember his service as a counselor in the bishopric of the San Gabriel Ward or his assisting in the family history library, or his work with the Boy Scouts. He didn’t remember that he had helped to build the chapel that I attended when I was growing up, and that, for years, even though he wasn’t a member of the Church, some members jokingly called him “bishop,” honoring him for his willingness to help.

As we talked about some of the many good things he had done, and the places he had seen, he remarked, “I’m learning a lot of new things. I’ll bet you are, too.” I wasn’t, of course. These were the things I had seen in and learned from my Dad. But when he finally said, with some relief, “I guess it wasn’t too bad a life. Maybe I did a few good things,” I was happy and proud to be able to answer him, “Yes, Dad, you did.”

I believe that my father is one of those to whom the Savior will say—perhaps already has said—in the words of the New Testament parable of the talents, “Well done, thou good and faithful servant: thou hast been faithful over a few things, I will make thee ruler over many things: enter thou into the joy of thy lord.” (Matthew 25:21.)

A modest and shy person, Dad would never have seen himself as a great man. Yet he was. In all the truly important things, he was. He loved my mother, and, to his very last day, worried about whether she was receiving adequate care. He was my first and only missionary convert. I was privileged to baptize him—and Kenneth to confirm him a member—on the night I was set apart as a missionary. Kenneth and I could have had no better father. When, just after his stroke, I was about to publish a book, it suddenly came to me with a flash almost of revelation that I had to dedicate it to my father, and how that dedication should read: Quoting Jesus’ description of Nathanael, I dedicated it “To my father, Carl P. Peterson—an Israelite indeed, in whom there is no guile.” (John 1:47.) Dad worried about that dedication. He was afraid that I was calling him “perfect.” I wasn’t, of course. But Dad was entirely without guile or deceit. He was a loving, gentle, patient man. Humble, self-effacing. Kind.

Of such is the Kingdom of Heaven.

I loved him, and I continue to love him, more than I have words to express.

Posted from Amsterdam, The Netherlands