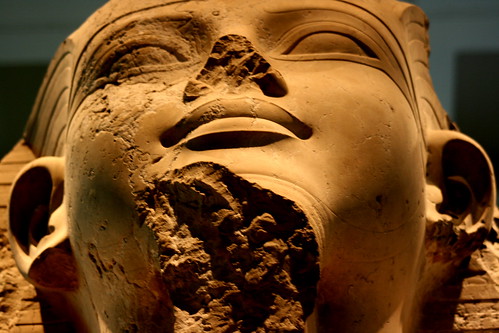

I am a pharaoh.

Or at least, I am one of his people.

As a white heterosexual male living in a racist, sexist and heterosexist world, I am the beneficiary of privilege solely because of what I look like. White progressives often like to think of ourselves as participants in liberation of the “oppressed.” We like to cast ourselves in the roles of Moses, Aaron and Miriam, or at least, as one of the Israelites walking through reeds and seas toward liberation.

In reality, I am more akin to the magician in Pharaoh’s court and the people living in comfortable complicity as a result of the oppression of others. I believe this is true of most white people in America.

I have spent most of my adult life confronting and coming to terms with my own racism, sexism and privilege, attempting to understand it and dismantle it. I am still a work in progress, as I think many are. Living within the racist and sexist structures of American culture, I am not sure if I will ever get to the end of the ways in which I am shaped by them and am complicit in them.

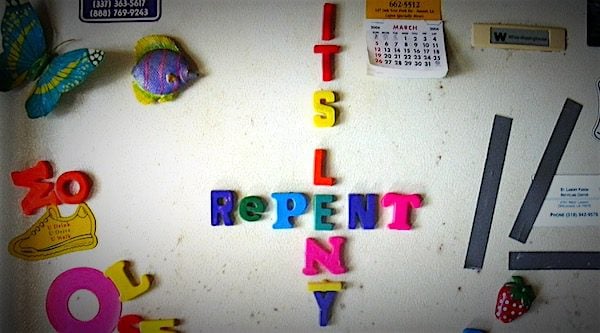

But, I try to listen and to learn and to respond. I try to resist the pharaoh mentality to harden my heart when hard words are spoken to me. I try to listen and hear with an open heart. Even when it hurts to do so. Even when to do so reveals yet another corner of my heart still warped by racism and sexism I didn’t know existed there.

This has been the spirit in which I have tried to hear the comments and constructive criticism of my post on Beyoncé. I’m not perfect, of course, but there is much that I am learning and, I hope, much from which I am growing.

When I wrote my original post, I did so in response to how I saw many white people, mostly men, respond to Beyoncé’s performance. Their comments brought to mind long-held cultural fears among many whites regarding powerful people of color. A number of their comments framed the performance along common racist stereotypes that portray Black people as hypersexual or as vixens. I felt this racist discourse resonated in these comments and so I pushed back against it in my post. Many people found meaning in what I wrote and I am glad for the conversation it started. And while I stand behind what I wrote, I am not arrogant enough to think that as a white male I have the best, the only valid or the corner of issues of racism and sexism. I know I have a lot to learn. (updated) Some have suggested this sounds too much like an apology for what I wrote yesterday. It is not. It is about how I am engaging in the massive conversation that post (of which I am proud) generated.

Some felt I went too far in the post, was overly optimistic, or offered too little or no nuance. Part of that is a fair criticism. Part of that is intentional. In my experience, trying to provoke white people to even begin to consider confronting their own racism requires this. Had I known this post would travel so much further than any other post I have ever written, I might have written it differently. The make-up and extent of my typical audience for which I write changed at about 2 p.m. yesterday. Others commented that I should have explored more fully the relationship between power and sex rather than set up a dichotomy. Again, this is constructive and a conversation that could occupy several dozen blog posts.

The overwhelming criticism I received deployed a familiar argument against certain kinds of media — the “What about the children?” defense. They argued that Beyoncé’s performance wasn’t kid-friendly, or analyzed the cut of her leotard or whether her costume was too revealing. I couldn’t help but think of Michal, David’s wife, who was scandalized when her husband showed too much skin at a rather public dance procession. Please forgive the strong language, I think I have to be careful if I attempt to understand an adult through the lens of a child and I think I need to be even more careful when asking a performer to take in mind how what they do will affect my children. This is particularly fraught where Black women are concerned, in my opinion. Black women are not the minders of white people’s children (overwhelmingly this comment came from white people). For me, (maybe not for you?), this hits too closely to asking Beyoncé, an independent, strong woman, to perform as a veiled Mammy. In the end, though, I am responsible for what my children watch, not Beyoncé. I believe the Super Bowl to be an adult event, and I wrote my blog post accordingly.

To be honest, I was caught off-guard by the passion with which this post was received. This, of course, reveals blindspots attributable to my own whiteness and privilege. I was unaware of the lengthy cultural discourse surrounding Beyoncé, her life and her career. I have learned from this, mostly that it is an exercise of white privilege to be unaware of important conversations surrounding a celebrity who is Black.

One post was hard to read for me. People started tweeting it and facebooking it in my direction in the afternoon. Social psychologist and author Dr. Christena Cleveland wrote, not necessarily in direct response to my post,

“As ‘powerful’ as she appeared on stage, Beyonce was still subject to the stringent rules and standards that white men set for black women. All other things (e.g., talent) being equal, she was only given ‘power’ because she happens to be the kind of black woman that white men like and because she was sure to ‘perform’ in a way that would be pleasing to them. To be blunt, she was treated like a 21st century ‘house nigger’ whose value will never outlast the duration of an erection.”

While I don’t agree with all of Cleveland’s excellent and profound post and I wonder how we might view sexuality differently, there is no doubt this hit me pretty hard. It was unsettling to ask myself whether I had unwittingly been duped into seeing Beyoncé’s performance through a social construction that allowed me to affirm it from a progressive point of view yet still participate in the perpetuation of racist and sexist oppression.

I am reflecting on Cleveland’s reading of the halftime show. I probably could have paid closer attention to my own whiteness and how that influenced my own reading of it rather than simply responding to it from within an overwhelmingly white context.

In other words, writing about race and sex has reminded me of who I am and who I am not.

I am a pharaoh.

But I am listening. I am trying not to harden my heart, but rather to open it.