I was dropping off a bag of stuff at Goodwill, and another car pulled up behind me. An older lady got out with one very pretty blue sweater in her hands. She gave it a once-over and started towards the drop-off. When she approached me, she held the sweater up.

I was dropping off a bag of stuff at Goodwill, and another car pulled up behind me. An older lady got out with one very pretty blue sweater in her hands. She gave it a once-over and started towards the drop-off. When she approached me, she held the sweater up.

“Do you need a sweater? This would look pretty on you,” she said.

I was sorry that I did not need the sweater. I was trying to get rid of stuff.

“It’s a good sweater. Paid a lot of money for it. It’s a shame I can’t find anyone to wear it.” She hesitated one last time, and relinquished the sweater to the thrift store.

I could feel her pain. It’s so hard to come to that crossroads, where you part company with a dream–in this case, the dream of the blue sweater, purchased with high hopes for some special occasion. Over the years, I’ve let go of many such dreams and only once have I returned to Goodwill to buy an item back (Favorite Hooded Sweatshirt, why did I ever want to quit you?).

How many times have I come to the conclusion that something in my home needs to go, but I don’t get rid of it because I can’t seem to do it in the right way? Someone else might not treat it well or recognize its value. Or worse, I might not get reimbursed for its value, even though I’ve already affirmed that it has no value for me, and that in fact, people pay good money on monthly terms to store their overflow in storage units while I have been storing this item for years for no cost at all in spite of the inconvenience of having it around collecting dust, and crowding me out of my home.

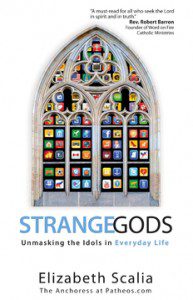

I’ve been reading Elizabeth Scalia’s new book, Strange Gods, and finding myself very turned on by her Benedictine spirituality. In the chapter on “The Idol of Prosperity,” Scalia discusses her commitments as a Benedictine Oblate to “resist cluttering up my life with anything that seems superfluous to my actual needs.”

“Because Saint Benedict was a sensible man, he wrote a sensible Rule. In it, he acknowledged that while attachments and ownership are to be minimized as much as possible, some monks will simply have more need of material things than others. But, Benedict said, instead of being a source of pride, it should be a source of humility, because it is better to need less. Every worldly, earthly thing you “need” is something else that can come between you and God.”

“It is better to need less” is the line that jumps out at me there, which means that my hazy foraging around my home, thrift stores, and the internet, thinking What do I need? –all while developing new plans and aspirations for my home and my life– is a sign of weakness. That I don’t actually have real needs, and that I’m manufacturing them as a source of entertainment, strikes me now as a peculiar kind of self-violence.

These are the kinds of discoveries one makes about oneself reading Scalia’s book, which guides us through a few everyday idols ranging from our own plans, to the internet, to the gods of sex and coolness, and how each of these idols upsets the peace that we all so desperately hope to achieve.

The internet, for example, “exploits that restlessness” of a heart that really yearns for God. Regarding the plans we make:

“To be inflexible about deviating from the plan is to erect a roadblock, an encumbrance–an idol–and put it in the way of what the Spirit might be trying to do with us and for us.”

Regarding the confusion that results when our super-idols rule the public discourse:

“We are in a place of deep cynicism, but that is rarely acknowledged, because so many of us residing within this disordered idol’s shadow confuse cynicism with cleverness. Similarly, we confuse love with hate, silence with peace, narrowness with breadth, and we do this mostly because everything is relative in this place….

The most insidious part of this hate collective is how easily we can slip into its influence through the simple error of attaching real but disproportionate feelings of love onto things which are often ultimately meaningless: I love my politics so much I must hate you for your policies; I love my church so much I must hate you for not loving it. I love yogurt, cheese, and butter so much I must hate you for being a vegan. I love my own opinions so much I must hate you for having your own.”

Like all really wonderful books, Strange Gods has caused me to make some reassessments in how I’m living my own life. My first pass is to reevaluate my gut reactions to internet feeds that contradict my most cherished religious and political opinions. Can I love the bearers of bad news in my life? What about the friends who make a great impression in person, but whose online persona is like a clanging gong in my psyche? If I can’t get past the persona to the real person, my next pass is to walk away from the technology that enables this objectification of others–thus wiping out two idols with one stone.

After that, of course, I’m left to my own devices in this little house with my family and my things. Am I going to let my desires for more information, more stuff, more desire even, bury me?

Over the course of the next year, I would like to divest myself of fifty percent of my belongings. Fifty percent? you say, That’s a lot of stuff. When I open my closet, I feel oppressed by what I find there. Mainly, I find nothing, because half of my clothes are hidden behind other clothes. For years, I’ve been adding to the contents of this closet, while subtracting, fractionally, much less.

Not only that, with eight people bringing material goods into the home, it must be someone’s full-time job to also be sending goods out of the home lest we crowd ourselves out of existence.

I don’t want to keep feeling a pang at even the hint of the need. I can be comfortable with the ebb and flow of goods on the shelf in my pantry. Sometimes the shelves will be full, sometimes empty, but neither should cause panic. Currently both do, probably because I have made an idol of my comfort even while that idol makes me physically uncomfortable.

I love the anecdote Scalia sites about Dorothy Day, how when someone donated a diamond ring to the Catholic Worker Movement, Day passed it on to a homeless woman who frequented the shelter. When questioned why she didn’t sell the ring to buy the woman lodgings, Day responded that:

“the woman had her dignity and could do what she liked with the ring. She could sell it for rent money or take a trip to the Bahamas. Or she could enjoy wearing a diamond ring on her hand like the woman who gave it away. “Do you suppose, ” Dorothy asked, “that God created diamonds only for the rich?””*

It is a tremendous freedom to have such detachment from ideas and material objects, not to begrudge someone else’s enjoyment of the things and opinions to which I feel entitled. All of God’s creation has dignity–the wealthy, the poor, the ignorant, and the so-called intelligentsia.

This is the heart of Scalia’s message, that the idols we place before God, rather than providing the comfort, affirmation, and satisfaction we desire, really only enslave us.

*From Jim Forest’s essay “What I Learned about Justice from Dorothy Day”