The man who cannot learn from fiction because it is not literally true is like the man who cannot watch an event on television because it is not “literally” before his eyes. He is missing the truth in the representation of reality.

Fiction has taught me as much as n0n-fiction. That Hideous Strength, Jane Eyre, the myths of Republic, and any film by Tarkovsky have given me truths and those truths have helped me. There exists, however, a certain weirdling that hears “fiction” and thinks: “false story.” Once I met a weirdling Christian who believed all the parables of Jesus must be “literally true” or the weirdling would not be able to trust Jesus. I began to worry about telling this person a joke unless the joke were based on a true story. After all when I said, “Why did the chicken . . .” I never prefaced it with “just kidding, there was no chicken, no road, and no other side.”

Yet for every Christian I have met with this idea, I have met a score of atheists. Much Internet criticism of Scripture rests on showing some part of the sixty-six books of the Bible (filled with many genre) is fiction. What are examples? Jesus told parables. Apocalyptic literature (parts of Daniel and all of Revelation) are written in hyperbolic images that are not “literal truths.” Poetry is . . . poetical. Even the “history” of the Old Testament is history as the ancients understood history, not as we understood history.

When I wear a costume to a party, anyone deceived by the costume to think: “Look a starship captain!” has made a category error. Be not deceived by the statue of John Wayne at the Orange County Airport: John Wayne was a real man, but this is not John Wayne. It is a work of art, a fiction, but one can still learn about John Wayne or at least our perceptions of Wayne from it.

And, yet, though the Orange County Airport contains this fiction and is even named “John Wayne” when “John Wayne” was not even the man’s real name, I can still fly on planes and trust them. The blend of fiction and fact in the airport does not confuse me: I fly on real planes and learn real truths from actual sculptures.

In the same way, the Bible is literally true if you read it literarily. This is so obvious that one wonders how the fundamentalist or the atheist (of this sort) reads most works of literature . . . only to discover that they often do not read fiction. At the best, such folk think of fiction as entertainment, the way some film goers cannot discern the difference in seriousness and intention between a film such the Passion of Joan of Arc and Legally Blonde II.

Reading any complicated work of literature is hard, but there are silly objections educated people can dismiss if they simply use the same reading skills to the Bible they apply to Shakespeare. Here are five of those superficial objections:

“After all, if this part is fictional, or might be fiction, how do we know this other part isn’t?”

One way to tell the difference is to learn the clues of genre. If a story starts “Once upon a time”, English readers know what is coming and that what is coming might be important, meaningful, and insightful, but it is not going to be “history.” Biblical and other forms of ancient literature contain such genre clues to educated readers. Any good book on hermeneutics can give you those rules.

Next, one must ask: does the message or intention of the account depend on the (literal) truth of the account. If the message of Jonah is that God is a God of love, reaching out even to the enemies of God’s people, the truth of this message would not depend on whether Jonah was a “real person” or was swallowed by an actual whale. There are other reasons to think Jonah historical, but the central message of the story is not one of them.

“How do we know what to believe if this work is a fiction?”

A reader always must ask: what is the author intending to say in the story. If I intend to tell you the actual history (in the modern sense of the term) of the world, then my work had better be accurate. But suppose that Plato is telling us an allegorical creation account in his Timaeus for teaching purposes. Can’t we accept what he is saying if the allegory is persuasive to us as an allegory?

Nobody thinks that the story of men trapped in a cave (the famous cave analogy) of Book VII of the Republic is literally true, but I have reflected on it for twenty-five years (or more!) and received insight into the human condition. If I can do this for Plato, then can’t this be done for the allegorical or parable parts of Sacred Scripture?

“How could God deceive me about the nature of this book?”

God does not deceive the man who is ignorant: ignorance deceives a man. If we insist on reading a book badly, the book will seem bad. If we demand that a text be plain without doing the plain old hard work to master the text, then the problem is not in the text.

In the same way, the fact that some Christians read badly does not justify critics of Christianity in taking a bad reading as the true reading. Surely nobody is foolish enough to believe that the Bible is “a book” when it is a collection of (at least) sixty-six books.

“Isn’t this fiction like some older or other religious fiction?”

There are generally one of three mistakes being made by the person making this claim. First, he or she will often claim that Jesus is like some person “A.” “A” was “born of virgin” or “rose from the dead.” However, if you ask if we have any texts about that person predating the coming of Christianity to the region, the answer is (usually): “no.”

We know that some movements, such as neo-Platonism, borrowed Christian themes and images and “pre-dated” their stories in their (losing) intellectual competition with the next faith. If god “A” is really like Jesus and isn’t just “Jesus” in pagan garb, we would find texts older than Christianity making the claims. This is rarely the case.

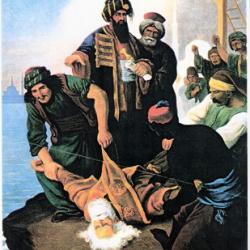

Second, the comparisons where they are valid are superficial: compare the “raising from the dead” of Osiris and Jesus. They are nothing alike except the fact that both were dead and then were not dead. Almost any literate person can tell the difference in tone between the Egyptian myths of Osiris and the Gospels.

Finally, Christianity is true, so it is archetypical. We are telling a story (a true story) about the world: creation, fall, redemption, and glorification. If it is true, then we anticipate every culture tapping into some element of those truths. We do not claim to be unique, just to tell the story best, in the most complete manner, and in a way that is (historically) true where it needs to be.

Jesus rose from the dead: really.

“If this account is like a known fiction, shouldn’t we believe the Bible account to be fictional?”

Generally lurking around this argument is the assumption that miracles are dubious or that we know they do not happen, but I hate to accuse atheists of confusing one argument for another.

Bluntly, fictional stories are the basis for true events all the time. We often live literally! I married my wife patterning the relationship after that in Wuthering Heights and then later in Jane Eyre. My marriage is no less real because of intentional similarities to fictional relationships.

Finally, we all accept that some fictional stories are deeper, truer to reality, than other tales. The relationships in Twilight are less true to reality than the relationships in Saving Alaska, though both books are fiction. Some fiction is better written, more profound, than other fiction for the purpose of learning. Anybody can see this with even the trashiest fiction: 1970’s Spiderman comics are much less profound that 21st century Spiderman comics.

Both are fiction, but one is more developed and more sophisticated. Homer is more intellectually interesting than Homer Simpson, though both are probably fictional characters. The next time a fundamentalist Christian is confused about “fiction”, ask if Jesus is made of wood because the Savior said He was “the door.” Ask an atheist if the “Courtier’s Reply” is useless or the Gettier Problem is nonsensical because both rely on “fictional tales” to make a point.

One rule has never failed me: the person who confuses “fictional” with “false” is a dullard.