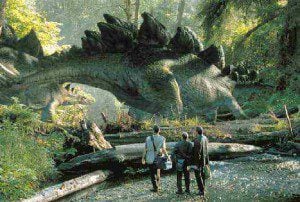

Atheism may be in vogue among people who like to read, but movie audiences still need something to believe in. That, at least, is one way to interpret the implicit pantheism Steven Spielberg has injected into The Lost World and its predecessor Jurassic Park, both of which he adapted from the considerably more sophisticated novels of Michael Crichton.

Atheism may be in vogue among people who like to read, but movie audiences still need something to believe in. That, at least, is one way to interpret the implicit pantheism Steven Spielberg has injected into The Lost World and its predecessor Jurassic Park, both of which he adapted from the considerably more sophisticated novels of Michael Crichton.

Crichton’s original story was a cautionary tale about the dangers of commercialized science, but he also took an explicit stand, through the character Ian Malcolm, against attempts to find any sort of higher meaning in nature.

In one novel, he dismissed creationism, even the evolutionary kind, as “just plain wrong.” In the other, he refuted the notion that humans were somehow meant to protect the earth: “Let’s be clear. The planet is not in jeopardy. We are in jeopardy. We haven’t got the power to destroy the planet — or to save it. But we might have the power to save ourselves.”

Contrast that approach with the worldview of the films. In Jurassic Park, Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) — contrary to the “chaos theory” he supposedly espouses — equated nature with the divine will. Nature, he declared, had “selected” the dinosaurs for extinction; in a later scene, he mused, “God creates dinosaurs. God destroys dinosaurs. God creates man. Man destroys God. Man creates dinosaurs.”

The Lost World goes further, idealizing not only nature but the potential role of humans within it.

An awe of sorts

Critics have panned the film for lacking Spielberg’s usual “magic” touch, but an awe of sorts persists: nature retains a purity that people have lost. Tyrannosaurs may think nothing of ripping a man in two for a snack, but they also display the closest thing this film’s got to a caring nuclear family. While the human relatives bicker without ceasing, the greatest act of parental love comes from an adult dinosaur teaching its young to hunt, and kill, a wounded bad guy.

Spielberg’s film also rehabilitates John Hammond (Richard Attenborough), the wealthy entrepreneur who created the dinosaurs and caused all this trouble in the first place, by having him hire an Earth First activist (Vince Vaughn) to sabotage the efforts of hunters and less scrupulous capitalists who want to exploit the dinosaurs for profit.

Hammond was killed by his own creations in the original novel, but in the newest film it is he who asks us to venerate these life forms — albeit from a distance. “Trust in nature,” says Hammond. “Life will find a way.”

As Christians, we know that the answer lies somewhere between — or, rather, beyond — both the atheism of the books and the pantheism of the films. Humans, as C.S. Lewis put it, are amphibious creatures; we feel an appropriate kinship with nature, yet we are also created in the image of a God who has given us stewardship of his earth, and it is ultimately in him, not nature, that our trust belongs.

— A version of this review first appeared in ChristianWeek.