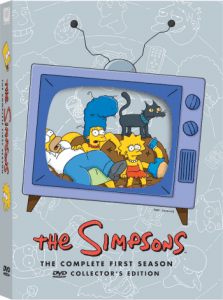

• The Simpsons: The Complete First Season, Fox Video, 2001.

• The Simpsons: The Complete First Season, Fox Video, 2001.

• William Irwin, Mark T. Conard, and Aeon J. Skoble, eds.: The Simpsons and Philosophy: The D’oh! of Homer, Open Court, 2001.

• Mark I. Pinsky: The Gospel According to the Simpsons, Westminster John Knox, 2001.

I DON’T watch a lot of television, but I have always been a fan of The Simpsons.

Homer, Marge, Bart, Lisa and Maggie made their debut in the late 1980s, in a series of short animated sketches that played between skits on The Tracey Ullman Show. These shorts — which poked fun at typical family activities like going to zoos and funerals and singing creepy bedtime lullabies — were a hit on the animation-festival circuit, and it wasn’t long before this wonderfully dysfunctional family was given its own half-hour show, beginning with a Christmas special in 1989. That special, and the rest of the show’s first season, are now available on DVD.

It is fascinating to see how much of the show’s irreverent yet fundamentally affectionate sense of humour was there from the start. Homer is a terribly anxious father — at one point, worried that his family might make a bad impression on his boss, he chases his children around a company picnic and yells “Be normal!” — but his anxieties stem, in part, from the fact that he does care deeply about his family. When the show was just a few weeks old, I happened to join a Bible study that was led by a couple of Simpsons fans, and we agreed that it was the most realistic sitcom on TV, in contrast to relentlessly sunny fare like The Cosby Show.

Many of our fellow believers saw things differently, though, and criticized the show for allegedly subverting family values. They especially objected to Bart, a fourth-grade ‘underachiever’ who disrespected his father, ran naked through the house, and peppered his speech with words like ‘hell.’

But a funny thing happened over the show’s first few years. As time went by, Bart’s in-your-face catchphrases (“Eat my shorts,” etc.) fell out of fashion, and people began to use one of Homer’s favorite expressions (“D’oh!”) whenever they made some sort of mistake. Audiences no longer merely laughed at the Simpson family or indulged in some of the characters’ ruder habits; they identified with the characters and, through them, laughed at their own foibles.

Along the way, The Simpsons became one of the most culturally diverse shows on television. Its surreal and thoroughly postmodern sense of humour incorporates both broad farce and sharp intellectual satire, and it appeals to highbrows and lowbrows alike — architect Frank Lloyd Wright and castrati singers are as good for a laugh as Saturday morning cartoons and the latest pop songs. Because it is animated, the few actors who work on The Simpsons can provide voices for dozens of characters, and this has created a thriving sense of community among the residents of Springfield.

Most remarkably, The Simpsons is one of the few shows that treats faith seriously as an active part of the average North American’s life. All the Simpsons go to church, and for Marge and Lisa, at least, it is more than just a habit. The show has also been quite sympathetic to Ned Flanders, the Simpsons’ ultra-evangelical next-door neighbour. Ned is a caricature, true — but then, so is everyone else on the show. When Homer sneers at Ned’s faith, we are no more meant to agree with Homer’s bigotry than we were meant to agree with Archie Bunker’s racism. Ned wrestles with doubt and anger, but he does try to love his neighbour, and he’s one of the few people in Springfield who doesn’t reek of hypocrisy. As even Homer admits, in one of his rare insightful moments: “If everyone here were like Ned Flanders, there’d be no need for heaven. We’d already be there.”

These days, it is difficult to find people who openly admit to hating the show; indeed, many people now take it very seriously, and use it as a springboard for discussing larger issues. Two such books have come out this year, and, fittingly, they both pay homage to previous books in their genre. The Simpsons and Philosophy: The D’oh! of Homer, a collection of 18 essays, cleverly alludes to Benjamin Hoff’s The Tao of Pooh; while Mark I. Pinsky admits that his book, The Gospel According to the Simpsons, was inspired by Robert Short’s classic, The Gospel According to Peanuts.

These days, it is difficult to find people who openly admit to hating the show; indeed, many people now take it very seriously, and use it as a springboard for discussing larger issues. Two such books have come out this year, and, fittingly, they both pay homage to previous books in their genre. The Simpsons and Philosophy: The D’oh! of Homer, a collection of 18 essays, cleverly alludes to Benjamin Hoff’s The Tao of Pooh; while Mark I. Pinsky admits that his book, The Gospel According to the Simpsons, was inspired by Robert Short’s classic, The Gospel According to Peanuts.

The Simpsons and Philosophy is not all that concerned with religious matters, per se, but in addition to the essays that compare Homer to Aristotle and Bart to Nietzsche — in both cases, the Simpson in question is found wanting — there are some that ask important questions about the relationship between morality and faith. Gerald J. Erion and Joseph A. Zeccardi observe that, although Marge is a religious person, she will follow her conscience and try to do the decent thing, even when it means ignoring the advice of religious authorities. And David Vessey, with a little help from Kant, explores how it is possible for Ned to love his neighbour without imposing his beliefs on them.

Other contributors argue over whether the show has a moral agenda. In a somewhat cynical essay, Carl Matheson claims that The Simpsons has no message beyond “hyper-irony,” and that the show is intended “primarily as a theatre of cruelty”; any positive elements are there, he says, just to make it easier for the audience to come back week after week. Paul A. Cantor, however, says the show affirms the value of the nuclear family within a larger community, and thus makes a “profound comment” that stands in stark contrast to the many TV shows that have focused on the lives of isolated individuals or questioned the need for two parents.

Pinsky shares this positive appraisal of the show, for the most part, in The Gospel According to the Simpsons. Pinsky, who is Jewish, is a religion reporter for the Orlando Sentinel in Florida, and his book summarizes the main spiritual themes that have been addressed by The Simpsons, focusing on its treatment of mainline Protestants, evangelicals, Catholics, Jews, Hindus and assorted subjects such as the Bible, morality and prayer. Along the way, Pinsky makes several astute observations, noting that there is a curious lack of Muslim characters on the show, and that there is no real discussion of the Protestant belief in salvation by grace through faith; instead, everyone on the show seems to believe they can earn God’s favour through their works.

Pinsky shares this positive appraisal of the show, for the most part, in The Gospel According to the Simpsons. Pinsky, who is Jewish, is a religion reporter for the Orlando Sentinel in Florida, and his book summarizes the main spiritual themes that have been addressed by The Simpsons, focusing on its treatment of mainline Protestants, evangelicals, Catholics, Jews, Hindus and assorted subjects such as the Bible, morality and prayer. Along the way, Pinsky makes several astute observations, noting that there is a curious lack of Muslim characters on the show, and that there is no real discussion of the Protestant belief in salvation by grace through faith; instead, everyone on the show seems to believe they can earn God’s favour through their works.

Pinsky also probes the minds behind the show, interviewing several of its writers and producers, a few of whom are Christian. Series creator Matt Groening declined to be interviewed for the book, so Pinsky relies on other sources to flesh out Groening’s own religious influences. Among other things, he finds that Groening’s father came from a Mennonite family, and that Krusty the Clown, an abrasive children’s entertainer, was inspired by a Christian clown from Portland named Rusty Nails. “I couldn’t get past the idea that this was a nice clown with the scariest name possible,” Groening once told TV Guide.

The Gospel According to the Simpsons sometimes reads more like a collection of facts and episode synopses than an engagement with ideas — like a journalist, Pinsky lets his sources do the interpreting — but it’s a must-read for anyone who wants to keep tabs on the relationship between faith and popular culture. And since the show is embarking on its 13th season, starting November 11, it’s safe to say The Simpsons will give us plenty more to think about in months to come.

— A version of this article was first published in BC Christian News.