Talk about timing. The same day a new movie about Martin Luther opened in Canadian theatres, the Daily Telegraph reported that German archaeologists had discovered the toilet on which he allegedly composed the 95 Theses that sparked the Protestant Reformation in 1517.

Talk about timing. The same day a new movie about Martin Luther opened in Canadian theatres, the Daily Telegraph reported that German archaeologists had discovered the toilet on which he allegedly composed the 95 Theses that sparked the Protestant Reformation in 1517.

“This is a great find,” said Stefan Rhein of the Luther Memorial Foundation, “particularly because we’re talking about someone whose texts we have concentrated on for years, while little attention has been paid to anything three-dimensional and human behind them.”

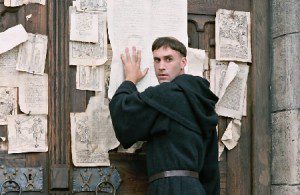

Giving human dimension to popular historical figures is, of course, one of those things films can do especially well. But Luther, which was finally released in this country over a year after its premiere in the United States, is not as satisfying an example of this as it could be.

Directed by Eric Till (whose resume includes everything from Bonhoeffer: Agent of Grace to Red Green’s Duct Tape Forever) from a script by Camille Thomasson and Bart Gavigan, Luther aims to make its protagonist more of a hero than the warts-and-all human he actually was.

Granted, in keeping with our current era’s emphasis on personal doubts and frailties, the film does go further to humanize the Reformer than did, say, the 1953 film Martin Luther.

Instead of settling for a calm and authoritative historical pageant, the new film uses tight close-ups and restless camerawork to portray Luther’s epileptic seizures and to convey his darkest fears, and to suggest how these things may have helped to shape his personality.

But unlike, say, the 1973 film Luther, there is practically no reference whatsoever to the crude, scatological, and vehemently anti-rationalist elements in Luther’s teachings. There is, so to speak, no reference to the very earthy toilet which the historians now find so key to the man.

The result is an unbalanced portrait of Luther that is at once both sympathetic and triumphalistic. He obviously has his demons, as do we all, but his cause is always right and he never says or does anything particularly scandalous — unless, of course, you happen to side with his Catholic opponents, who are given a mostly two-dimensional treatment.

Perhaps the most striking example of how this film massages the facts is the way it treats the Peasants’ War. In the 1520s, peasants took up arms against the German princes, and Luther, after an unsuccessful attempt to negotiate the peace, wrote a tract urging the princes to “smite, strangle, and stab” the peasants, “just as when one must kill a mad dog.”

This conflict took centre stage in the 1973 film, but nothing so bold comes through in this newest version. Apart from a scene in which Luther (Shakespeare in Love‘s Joseph Fiennes) stands up to a gang outside a church and defends a couple of priests, his role in the war is limited to mourning the bloodshed and wishing that both sides were not so prone to misunderstanding his message.

There’s no question the film is ambitious; it packs a couple decades’ worth of Reformation history into just a couple hours of screentime, and it takes full advantage of its European locations and detailed production design to convey a sense of authenticity.

The film also boasts some intriguing performances, particularly where Alfred Molina (Spider-Man 2), as the villainous indulgences peddler Johann Tetzel, and Bruno Ganz (Wings of Desire), as Luther’s sympathetic Augustinian mentor, are concerned; alas, Peter Ustinov, in his final screen role, lacks his usual wit as Luther’s protector Frederick the Wise.

It is also good to hear stirring pronouncements of faith in a film that has good production values and has even received decent theatrical distribution. But the film’s grasp of theology, both Catholic and Lutheran, is a bit vague and slippery, and of course, Christians of other denominational stripes may find the dialogue even less compelling.

In the end, however, the film isn’t really about taking a stand for any particular set of beliefs. The end titles tell us that Luther paved the way for “religious liberty”, and this is a remarkably misleading note on which to conclude the story, for two reasons.

First, Luther’s emphasis on personal conscience over traditional doctrine helped pave the way for the individualism and heightened skepticism of the modern era. And second, the historical Luther himself did not want to achieve “liberty”, but to reform the Church, and he actively condemned those fellow Protestants who disagreed with him on various teachings.

Luther and the movement he founded were full of such contradictions, but the new film passes them by in favour of a broader message of tolerance, tailored for our ecumenical times. Tellingly, many evangelicals have endorsed this film simply because it presents a basic gospel message. But the man through whom that message was preached is still waiting to be fleshed out.

Internet Movie Database | Movie Review Query Engine

USA: PG-13 | BC: PG | ON: PG

— A version of this review was first published in BC Christian News.