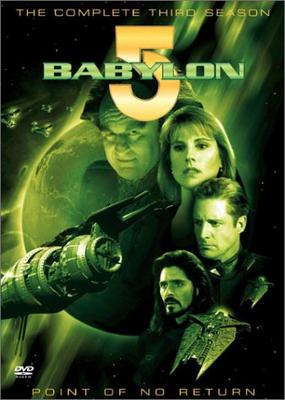

One of the first conversations between my wife and myself concerned DVDs and home entertainment options, and somewhere in there, she mentioned that she wanted to own the entire Babylon 5 series some day.

One of the first conversations between my wife and myself concerned DVDs and home entertainment options, and somewhere in there, she mentioned that she wanted to own the entire Babylon 5 series some day.

Nearly two years later, my friend Betty gave us the first season as a wedding present — and my wife and I managed to watch most of it on the honeymoon, in between going for walks and, um, other activities. Since then, we’ve picked up seasons two and three, and so far, we are four episodes into the latter.

I have been impressed throughout by the show’s sensitivity and complexity where the question of religion is concerned. Unlike, say, Star Trek — where religion is something the aliens do, while human beings apparently have no more need for faith or spirituality (except in the case of, say, Native Americans, who are still sufficiently “other” by mainstream cultural standards) — this show recognizes that human religious practises will continue into the future, and it gives each of the alien races at least one religious system that forms an essential part of their self-identities.

It is interesting to wonder how these themes might have been developed if Commander Sinclair (Michael O’Hare), who was trained by Jesuits, had remained in charge throughout the entire series; instead, he was replaced by Commander Sheridan (Bruce Boxleitner) in season two — because of pressure from the studios, who wanted a better-known actor in the lead, I believe — and I guess it would have been a little too coincidental if two commanders in a row had had the same religious background.

And lately, the episodes have been rather interesting. Near the end of season two, there is an episode that portrays Jack the Ripper — yes, as in Star Trek, it seems this 19th-century character will outlive us all — as a former religious fundamentalist of sorts who believed it was his duty to kill sinners, and who was then abducted by the Vorlons and then turned into a relentless skeptic who seeks to deprive other people of their religious certainties. It’s a striking portrayal of how some of the worst religious zealots can end up being some of the worst anti-religious zealots.

Most recently, we watched ‘Passing Through Gethsemane’, the fourth episode of season three. Wow. Brad Dourif (now known to Tolkien fans as Grima Wormtongue) as a sincere, penitent Franciscan monk named Brother Edward? Fascinating. And his conversation with Ambassador Delenn about the emotional centrality of the Garden of Gethsemane to his faith is also quite interesting — not least because she says something to the effect that, in Minbari thought, consciousness is the universe’s way of trying to understand itself, yet the episode revolves around scientific devices and themes such as memory erasure, and the role that memory plays in forming personalities.

There is a mysterious link between the soul and the mind that this episode touches on in a disturbing and fascinating way, and I can only wish that I had been aware of this particular episode before I spoke on ‘Memory @ the Movies‘ at the Imaginarium at last year’s Cornerstone festival (FWIW, I eventually distilled my notes for those seminars into this brief article for Books & Culture).

Alas, I didn’t entirely “buy” the episode on dramatic terms, especially in its very last minutes. I do like the idea that society, in an effort to be “humane”, might abolish the death penalty in favour of erasing a man’s memories and giving him a new personality disposed towards community service; it brings to mind the question I once asked a radio evangelist and his guest, back in the ’80s, regarding whether we would remember our sins in Heaven (if so, then how perfect could we be? if not, then would we really be the same people?). And it is touching to see how Brother Edward is profoundly troubled by the discovery that he was once a serial killer; in a way, his debt to society has been paid — certainly the courts are satisfied — but he still believes there is a “stain” on his soul that must be atoned for somehow. And as with Total Recall (1990), so here — if a “bad” person is reprogrammed with the memories of a “good” person, what significance do the “good” man’s actions have? Are his choices still “free”? And so on.

But the very rushed way that Brother Edward’s killer is himself memory-wiped, as though he were somehow on the same level as a repeat offender or as though the courts would have rushed him through to his judgment so quickly — this part of the story does raise interesting questions about our ability to forgive others (as embodied by Sheridan’s reluctance to shake the killer’s hand), and it does raise interesting questions about whether people can ever truly forgive themselves if their memories are not wiped first, but in terms of dramatic world-creation, it does not convince me; in Tolkien’s terms, I can no longer create belief in this world at this point but must now “suspend disbelief” and “condescend” to it.

And that’s before we get to my concern over the way Brother Theo, the head of the Franciscan order, seems to just accept that this is the way things are done, when perhaps, like the minister in A Clockwork Orange (1971; my comments) who objects to Malcolm McDowell’s reprogramming, he ought to be protesting against the intrusion of technology into spiritual matters.

Nevertheless, I am still rather impressed. Brother Edward doesn’t abandon his faith when he finds out why he is predisposed towards serving others; the only thing that matters to him is that he might not have dealt sufficiently with the “stain” of his sins on his soul. (And this, BTW, is another reason why I think Brother Theo and the others should be a little less sanguine about memory wipes or personality deaths.) And this raises another interesting set of questions, for me. As I understand it, one of the things that distinguishes Orthodox theology from Catholic and thus Protestant theology is that the Orthodox do not see sin as a “stain” but, rather, as a “separation” from God or an “absence” of sorts — this is why the Catholics have the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, whereas the Orthodox do not, at least not in the strictest sense. So I wonder if an Orthodox response to Brother Edward’s situation might be different — and if so, in what way.