I saw The New World twice last December, once at a critics’ screening in Vancouver and once on a junket in Los Angeles, and both times, the film that I saw was 149 minutes long. But the version that was released across North America in January was 135 minutes long, and not only were some bits cut out, but other bits were added to the film, as well. So I have been meaning to see the shorter version for quite some time — and tonight, I finally got around to doing so, at the lovely VIFC theatre, as part of their Terrence Malick retrospective.

I saw The New World twice last December, once at a critics’ screening in Vancouver and once on a junket in Los Angeles, and both times, the film that I saw was 149 minutes long. But the version that was released across North America in January was 135 minutes long, and not only were some bits cut out, but other bits were added to the film, as well. So I have been meaning to see the shorter version for quite some time — and tonight, I finally got around to doing so, at the lovely VIFC theatre, as part of their Terrence Malick retrospective.

Since it has been seven months since I saw the longer version of this film, I am not entirely sure what bits are new and what bits are missing from the shorter version, though I have a few ideas.

Part of my uncertainty here stems from the fact that Malick is such a poetic, impressionistic filmmaker that his images don’t always follow a logical narrative sequence — and if you’ve got a memory like mine, which tends to remember the structure of a story and then fill in the gaps, it is easy to forget seemingly random or loosely connected images after only one or two viewings. This, by the way, is one of the reasons I love Koyaanisqatsi (1983); there are so many images packed into that utterly plot-less movie that it feels like I’m finding something new with each viewing.

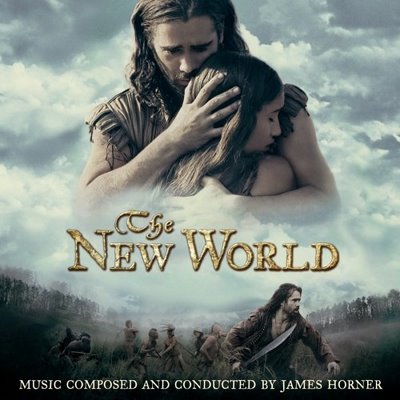

The greatest re-discovery on viewing The New World this time, for me, was the music. At the junket, the studio gave us all free copies of James Horner’s soundtrack album, and I have listened to it frequently ever since. But, gosh, I think easily less than half of that 80-minute album must be in the actual film itself. And some of the film’s most sublime musical moments are completely missing from the album — partly because a number of those scenes make use of pre-existing works by Wagner, Mozart and the like, and not original Horner compositions. (To the extent that a Horner composition can ever be called “original”.)

I am especially intrigued by the way Malick uses a Mozart piano concerto to signify John Smith’s feelings about Pocahontas (never mind that Mozart would not actually compose this piece until almost 180 years later), and how this contrasts with a much more tentative bit of solo piano that accompanies the later courtship between Pocahontas and John Rolfe. I don’t recognize the latter bit of music, and I wonder if it is an original Horner piece that was cut from the CD, or if it is one of the more obscure pre-existing works. But the impression I get from these musical choices is that Smith is imposing an established, prefabricated, and essentially European template on his relationship with Pocahontas — for all his admiration of the Native way of life, he still sees it essentially through European eyes, and with a European agenda in mind — whereas Rolfe, although a European himself, is reaching out to her and trying to forge something new, something uniquely theirs. But like I say, that’s just an impression on my part; it could be that Malick had something completely different in mind.

FWIW, I also caught Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978) yesterday. I don’t think I like it as much as The New World, but it’s got plenty of fascinating images, too — the time-lapse plant growth, the fish swimming around the wineglass, etc. — and the storyline is replete with plot elements that seem almost biblical in origin.

Richard Gere kills a supervisor in a low-paying work environment and runs away? Moses, check. Richard Gere passes off his lover as his sister, and then she marries the local ruler, as it were? Abraham, Sarah, and Pharaoh, check. Plague of locusts? Check. I think we even see a fox running through a field on fire.

And perhaps the biggest surprise of Days of Heaven? Malick can shoot and cut an effective chase scene when he puts his mind to it. It’s not all slow-moving grass-waving-in-the-wind shots!