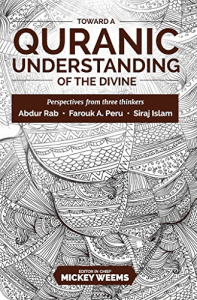

I picked up “Toward a Qur’anic Understanding of the Divine,” authored by Abdur Rab, Farouk A. Peru, and Siraj Islam and sponsored by Muslims for Progressive Values, with great expectations. I looked forward to a comprehensive discussion of what the Qur’an has to say about the nature of God. And I hoped to discover something I’d never heard before, garner some new insights, and gain a deeper understanding about familiar concepts.

I picked up “Toward a Qur’anic Understanding of the Divine,” authored by Abdur Rab, Farouk A. Peru, and Siraj Islam and sponsored by Muslims for Progressive Values, with great expectations. I looked forward to a comprehensive discussion of what the Qur’an has to say about the nature of God. And I hoped to discover something I’d never heard before, garner some new insights, and gain a deeper understanding about familiar concepts.

Food for Thought

There are certainly spots that are thought provoking enough that I set aside the book for a time to ponder what had been said. For instance, in Chapter 2 there is a brief discussion of how the Qur’an presents calls to action, addressing not “believers” (mu’mineen) but “those who have believed” (alladhina aamanoo) and the implications of that distinction. I spent some time mulling over the idea that calling people “believers” presents a finality as though belief were the end goal and a state of being, while addressing people as “those who have believed” conveys that belief is just a starting point, and that belief engenders a process and a way of being, bringing the believer into direct and continuing relationship with the Qur’anic text. It also suggests that “having believed” does not mean one will take action on that belief, and that one may not always believe, that belief is variable, and that it can easily wax and wane, or even go away entirely. From there, I was off to thinking about how a political or moral belief may suffer from the same vagaries, and how often we may hold fervent beliefs about a topic but do very little to effect change.

I really wanted the author to explore these ideas in depth with a thorough discussion of the various calls to action and a comparison with the concept of “those who believe and do good works” (aladhinna aamanoo wa amilu salihaat), but he skims quickly over the context and concepts of two or three of these Qur’anic passages without any further analysis of the idea. All in all, one suspects he was limited by strict guidelines on chapter length. Indeed, the book could easily have been twice its size and I think it would have benefited greatly from space for a more thorough investigation of the ideas the authors set forth. As it stands, it offers a tantalizing glimpse at various concepts, but feels more like a preparatory sketch than a fully developed painting.

Save the Best for Last

In general, I found the first two chapters less compelling than the latter ones. In the early chapters, there was not enough engagement with the text, not enough deep analysis, and too much philosophizing, much of which was at best dubious and at worst completely spurious. For instance, one of the authors states, “Belief in God and the Hereafter thus makes us more and more conscientious and conscionable, and requires us to seek knowledge and be just and kind.” (pg 8) Looking at Al-Qaeda, ISIS, and Boko Haram, this seems like a very questionable assertion. Another says, “Indeed, not only do we need God for our existence, but we also need Him for our guidance and evolution.” (pg 16) I know a lot of atheists who who would disagree vehemently.

The later chapters are more focused on the Qur’anic text and commentary on it, with less extemporizing by the authors. There was as a result more food for thought. I especially enjoyed the final chapter which focuses on understanding the Divine through the names and attributes of Allah found in the Qur’an. The authors include not only the classic 99 names of Allah we are all familiar with, but also extend their discussion to include other names found in the Qur’an like Rabb (Nourisher, Sustainer, Lord), which is often used in phrases like Rabb al Alameen (Sustainer of the Worlds) or Rabb al Samawai wal Ardi (Lord of the Heavens and Earth), and is the name by which supplicants call upon Allah. I was astounded to learn that Allah  is referred to as Rabb some 975 times in the Qur’an, far surpassing any of the 99 names. This sparked some reflection on the fact that Rabb comes from the same root as “raising a child” implying fatherliness while Rahman and Raheem come from a root that means “womb” presenting a very parental vision of God, as opposed to the typical English translation of “Lord” which has the connotation of a distant, arrogant, privileged guy who orders you around, takes your money, and hangs you if you shoot deer or collect firewood from “his forest.”

is referred to as Rabb some 975 times in the Qur’an, far surpassing any of the 99 names. This sparked some reflection on the fact that Rabb comes from the same root as “raising a child” implying fatherliness while Rahman and Raheem come from a root that means “womb” presenting a very parental vision of God, as opposed to the typical English translation of “Lord” which has the connotation of a distant, arrogant, privileged guy who orders you around, takes your money, and hangs you if you shoot deer or collect firewood from “his forest.”

Again, I was frustrated by exigencies of space limitations, especially when an author referenced a passage only by chapter and verse number rather than citing the whole text, which sent me scrambling for my favorite translation to find the reference as sometimes the points were not clear without the verse sitting in front of me.

Overall, I’d say the book is worth the read, despite it’s problems. I’m hoping the authors come out with an expanded version!

For full disclosure, I was co-founder of MPV in 2007, though I have not taken an active roll in the organization since 2009.